Like many Western societies, the UK prides itself on being tolerant. Fundamental British values are now widely promoted as democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, respect and tolerance. Not to be tolerant is to many, we are led to believe, to be narrow-minded, bigoted, exclusive, and potentially a lawbreaker. It is to be castigated as an instrument of hate, violence, prejudice, inequality, injustice and, of course, to demonstrate a cast of mind and style of behaviour that is essentially ‘un-British’. According to a May 2022 report by Hope not Hate, based on polling of more than 4000 people, England is now a more tolerant and multicultural society (with respect to race, religion and identity) than it was when a similar survey was undertaken in 2011. But is Britain really a tolerant society? In fact, should any society be unself-critically tolerant?

Britain isn’t unique in promoting its seemingly non-negotiable social virtue of tolerance. The DW Akademie in Germany articulates a similar position. According to DW Akademie, tolerance is the quality that ‘makes it possible for people to coexist peacefully’ and is ‘the basis for a fair society in which everyone can lead their lives as they wish’. To be tolerant is, it maintains, to ‘accept other people’s opinions and preferences, even when they live in a way that you don’t agree with’. It means ‘you don’t put your opinions above those of others, even when you are sure that you are right’. And, it argues, ‘Tolerant people show strength in that they can deal with different opinions and perspectives.’ What’s not to love in tolerance!

Tolerance, it’s a word used to inspire social cohesion and mutual respect, to demonstrate broad-mindedness and an inclusive morality. To the circumspect tolerance is also a word to monitor very closely. As the German Nobel Laureate author and social critic Thomas Mann (1875-1955) wrote in his novel The Magic Mountain (1924; ET 1927), ‘Tolerance becomes a crime when applied to evil.’ A critic in exile of the Nazi regime, Mann knew first-hand how tolerance could, and can still, become anything but a worthy public value. In fact, such are the risks attaching to indiscriminate appeals to ‘being tolerant’, we may wonder if we really do, or should, want tolerant societies?

So, what’s the matter with tolerance or being tolerant? Three problems are traditionally linked to the idea and ideal of tolerance. Look at them with me.

First, there is the semantic problem. In short, what does the word ‘tolerance’ really mean? Is everyone who uses the word ‘tolerance’ using it in the same sense, and does it mean what it did, say, 30, 50 or 100 years ago? After all, the word is used today in three quite different contexts which carry very different connotations. To most people it signifies a personal or communal reaction to differences of opinion or types of behaviour. It is synonymous, if you like, for forbearance and liberality, for leniency and magnanimity. But the word also carries the less creditable connotations of a person being lazy and indulgent, indecisive and undisciplined. Very different, then, from the word’s application, secondly, to various forms of prolonged physical, emotional, and psychological exposure to risks, threats, drugs or deprivation. Hence, the camel tolerates desert conditions, while a sick person’s body does and does not tolerate a particular drug for long periods of time. Here tolerance denotes capacity or resilience, acceptance, immunity and endurance. In line with this sense, material science and engineering have coopted the word tolerance, thirdly, to qualify and quantify strength and length. So, an iron bar is forged to a tolerance of ‘x’ 1000s of an inch and synthetic fibres are made with high tolerance levels to abrasion. Three quite different contexts and meanings of tolerance, with care clearly needed lest a person’s tolerance be measured like an iron bar, or a medical diagnosis be confused with a character trait! But, a range of meanings, which, as we will see later, suggest useful criteria to critique careless appeals to tolerance and the bald, popular, unthinking requirement to ‘be tolerant’.

The second set of problems with tolerance are socio-political. These have been recognized and debated for centuries. Philosophers and political theorists from Plato (428/7–424/3 BCE) onwards have registered the inherent paradox in tolerance. To Plato, and many who have thought long and hard about tolerance, a society that becomes tolerant without due care and attention risks destruction by the intolerant. As the Austrian-British philosopher and social critic Karl Popper (1902-1994) argues in his magisterial study The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945), maintenance of a tolerant society is inseparable from the seemingly self-contradictory principle of being intolerant of intolerance. Failure to do this, Popper is clear, expedites tolerance’s demise. But we shouldn’t – as some have argued – assume that Popper supports Plato’s case for a ‘benevolent despotism’ as the way to protect tolerance and suppress the noxious effects of unqualified freedom of thought, act and speech. No, in a nuanced note in Chapter 7 of The Open Society Popper distinguishes between a state’s right to suppress intolerance by force (if rational argument doesn’t work) and its democratic duty to suppress intolerance (using force as a last resort if necessary) in order to protect itself against itself. But Plato and Popper are agreed on this, whoever defines and monitors tolerance in liberal democracies it should never be an unaccountable majority, who can too easily turn freedom into illiberal expressions of intolerant populism. ‘The will of the people’ is to neither thinker never to be used as a knockdown argument to justify truth or freedom: it threatens states and undermines the stability of established democratic institutions.

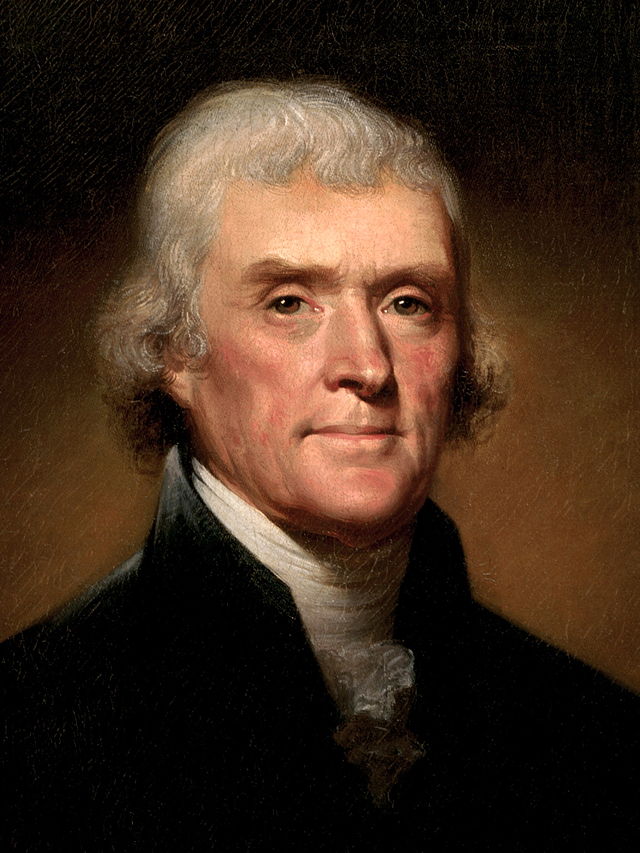

The third set of problems associated with tolerance are broadly speaking legal, if not also psychological. That is, they pertain to the legality and impact of those who use or abuse the gift of tolerance. We catch a glimpse of this issue in the 3rd US President Thomas Jefferson’s (1743-1826; Pres. 1801-1809) first inaugural address. With Enlightenment confidence in human reason and reasonableness, he says of those who threaten the peace and unity of his young country, ‘[L]et them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.’ Jefferson had deep faith in humanity and commonsense: these were a safe stronghold against the slings and arrows of the bigot and intolerant. To him, tolerance would shine when confronted by intolerance.

The last two centuries have seen Jefferson’s confidence in the self-regulating power of a tolerant society severely tested. Many philosophers and social theorists have revisited the issue, not least to assess the impact of intolerance on governance, democracy, and freedom of speech, with European democracies more inclined to penalise its intolerant fringe (i.e., censuring ‘holocaust denial’ and ‘hate speech’) and the US jealously guarding a citizen’s constitutional right to ‘freedom of speech’. But the debates have been and continue to be intense. Tolerance per se, as Plato foresaw, is a precious gift and a weighty responsibility.

The issue of tolerance goes to the heart of the nature of society. In his 1971 classic A Theory of Justice the American moral and political philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002) makes an explicit connection between a ‘just’ society and the paradox of tolerance. A just society will protect its citizens and institutions if they are threatened by an intolerance that seeks to limit freedom. As he says, ‘While an intolerant sect does not itself have title to complain of intolerance, its freedom should be restricted only when the tolerant sincerely and with reason believe that their own security and that of the institutions of liberty are in danger.’

Other authors have stressed different legal and psychological dimensions of the problem of tolerance. In his The Tolerant Society: Freedom of Speech and Extremist Speech in America (1986), Columbia University President and Law Professor Lee Bollinger (b. 1946) echoes something of Jefferson’s humanist confidence, arguing that a permissive attitude towards extremist speech strengthens a democracy by nurturing a spirit of self-control among those who are threatened; but he is at pains to stress, those who preach intolerance are breaking the law and worthy of censure. Even in the US a tolerant attitude to diversity of opinion and the right to ‘freedom of speech’, are not without limits. A 1987 Harvard Law Review article by Yeshiva University Professor of Law and Comparative Democracy Michel Rosenfeld (b. 1948) explains why: ‘[I]t seems contradictory to extend freedom of speech to extremists who … if successful, ruthlessly suppress the speech of those with whom they disagree.’ In other words, tolerance is tested by its immediate and ultimate effects on freedom, justice and society at large. And, as Raphael Cohen-Almagor (b.1961) argues in The Boundaries of Liberty and Tolerance: The Struggle Against Kahanism in Israel (1994), was Popper right to limit intolerance to physical harm? What of the psychological damage of intolerant words? Princeton philosopher Michael Walzer’s (b. 1935) monograph On Toleration (1997) bluntly asks, ‘Should we tolerate the intolerant?’ Like Bollinger, he is wary of those who benefit from social tolerance (like minority ethnic and religious groups) but abuse the gift in various expressions of intolerance. Walzer believes nevertheless that tolerant societies can in time inspire the intolerant to behave ‘as if they possessed this virtue’. Not all would agree, with ‘discourse ethics’ (pace philosophers Jurgen Habermas [b.1929] and Karl-Otto Apel [1922-2017]) acutely attentive to the impact of intolerance on intolerance. Tolerance is, it seems, a troubled product of troubled societies.

So where do we go from here? We have seen that blanket appeals to tolerance are risky. We have also seen that the relationship between tolerance and intolerance is a difficult one in law and in society at large, with some minority groups abusing the privilege of tolerance and tolerance itself being incautiously (and intolerantly?) celebrated. I have always found this succinct summary of a thoughtful Christian approach to tolerance, by the widely read author and popular teacher John R. W. Stott (1921-2011), particularly illuminating:

First, there is legal tolerance: fighting for the equal rights before the law of all ethnic and religious minorities. Christians should be in the forefront of this campaign. Second, there is social tolerance, going out of our way to make friends with adherents of other faiths, since they are God’s creation who bear his image. Third, there is intellectual tolerance. This is to cultivate a mind so broad and open as to accommodate all views and reject none. This is to forget G. K. Chesterton’s bon mot, ‘the purpose of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid’. To open the mind so wide as to keep nothing in it or out of it is not a virtue; it is the vice of the feebleminded.

What Stott is saying is, ‘Stand back from the word “tolerance” and think about what to say “Yes” and “No” to.’ From all we have seen above, we would do well to do just that. Tolerance can be a fine tool to build a wholesome society and a crude bulldozer to destroy it.

Mindful of the different uses of the word tolerance, and the history and present state of the debate, I suggest our attention focus on four key areas of controversy.

i. The verbal. The meanings of words evolve. Words are easy targets for the intolerant to use and abuse. I am not only speaking of those who use words to preach hate, but those who weaponize words like ‘tolerance’ and ‘intolerance’ and use them to justify themselves and condemn others. Evolving use of the term ‘tolerance’ in public and political materials in most Western liberal democracies sees it dangerously extended into a term of censure and control more than a principle inspired by genuine generosity and liberating breadth. The illiberalism Plato prophesied, and Popper feared, is eating away at the edges of the word tolerance. Intolerance is on the ascendant under the guise of the so-called ‘tolerant society’.

ii. The social. The dynamics of tolerance and intolerance map onto various expressions of ‘systems theory’, group dynamics, ‘balance theory’ and psychoanalysis. Fernando Aguiar and Antonio Parravano’s fascinating commentary on individuality and community, Tolerating the Intolerant: Homophily, Intolerance, and Segregation in Social Balanced Networks (2015), reveals how choice, negativity and ostracism impact a tolerant in-group member’s attitude to a tolerant outsider, and how intolerant insiders and outsiders threaten and disrupt their own and other groups unless they share to some degree their willingness to be intolerant. ‘Homophily’ (the preference to congregate with like-minded people) is a potent reality in evolving cultural dynamics. We accept cultural and attitudinal change – including towards tolerance – because we prefer the psychological ‘balance’ of continuity and conformity to the riskier social and emotional disruption of cognitive and cultural dissonance. As some psychologists would argue, the happier we are the more tolerant we are. But, and here Plato and Popper remain relevant, homophily is also the breeding ground of unthinking intolerance and ill-considered tolerance. To be reminded of how dangerous and complex this can be, recall Thomas Mann’s warning about Nazism or read the recently republished, classic study of American ‘Populism’ by University of Notre Dame professor Walter Nugent (1935-2021), The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism (1963, 2nd ed., 2013).

iii. The logical. There is more to the ‘paradox of tolerance’ than unthinking expressions of tolerance and intolerance may be ready to accept. Extension of the term ‘tolerance’ to the fields of material science and engineering is helpful here. In both contexts, ‘tolerance’ denotes something that is scientifically useful and empirically verifiable. Too often contemporary societal appeals to social, legal, and intellectual ‘tolerance’ lack that kind of rigorous accountability. They belong to the apple-pie moralism of ‘Be nice to one another’ more than to the sophisticated world of political theory and legally ratified ‘public values’. Is it really significant that 4000 people believe Britain to be ‘a more tolerant society’? The ‘paradox of tolerance’ would indicate it is more useful and logical to monitor the rise of intolerance (in all its forms), than confidently declare tolerance per se safe and well. Study of the ‘paradox of tolerance’ also suggests that ‘outsider’ voices and actions that oppose prevailing social mores may ultimately prove to be the salvation of society and indeed of tolerance itself. Conformist cultural expectations are far more dangerous than they appear.

iv. The moral, spiritual and ideological. As indicated earlier, claims for and against a society being ‘tolerant’ are often focused today on its attitude towards personal morality, cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity, and its willingness to accept and protect contrary opinions. Culture clashes occur when one expression of intolerance meets another, or one appeal to tolerance provokes an intolerant reaction. Modern Western democracies know all too well how tense, violent and unpleasant such clashes can be. So, what’s the solution? or isn’t there one? Come back to John Stott’s typology. There is much wisdom here. In a muddy quagmire of conflict, cultural competition, and intellectual confusion, he offers three solid, reasonable rocks to build upon; legal tolerance as a right of all before the law, social tolerance of our neighbour as a fellow human being, and the intellectual tolerance of a hungry heart and an open mind. But Stott was too acute a thinker to leave the issue there. Elsewhere he warned fellow believers, ‘Tolerance is not a spiritual gift; it is the distinguishing mark of postmodernism; and sadly, it has permeated the very fibre of Christianity.’ In other words, there is an appropriate type of intolerance: intolerance of moral and spiritual relativism, of ideological presumption and abuse, of simply anything that dehumanizes others or devalues their freedom and right – like yours and mine – to hold contrary opinions. ‘The Tolerant Society?’ – well, yes and no.

Christopher Hancock – Director