Conflict between India and Pakistan is not new. Periodic spats – some of them widely reported, others less well-known – blight their national histories.[1] When India and Pakistan agreed a full and immediate ceasefire on 10 May 2025, at the end of the recent confrontation, to most observers this was less an end to conflict and more a pause to prepare for future hostility and propagate the political rationale for continuing the dispute.[2] To war-weary citizens in both countries – particularly in the disputed region of Kashmir – this has happened many times; to the elderly, it stirs painful memories of Partition in 1947 and the prolonged birth pangs of their nation’s life.

A number of issues render the most recent clash between India and Pakistan significant. Three stand out.

First, though mercifully short-lived, the recent action by land and air was particularly violent. Missiles and drones hit military and civilian targets.[3] Parallels have been drawn with the May to July 1999 crisis in Kargil district of Ladakh (then part of Indian administered Jammu and Kashmir) and along the Line of Control (LoC). The Kargil conflict (known in India as ‘Operation Vijay’ [Lit. Victory]), was triggered by Pakistani insurgents on the Indian side of the LoC. During the fighting 520+ Indian and 2-3000 Pakistani were killed. In the most recent clash, 63 military and civilian personnel were killed. When added to the tens of thousands displaced by the conflict, casualty numbers and entrenched bitterness from this long-running dispute steadily increase.[4]

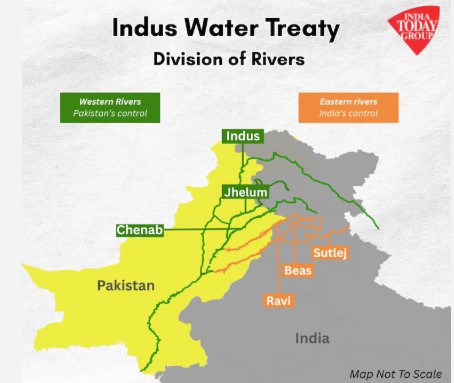

Second, when terrorists attacked Pahalgam in Kashmir on 22 April 2025, SE Asia was taken ever closer to nuclear war; perhaps nearer than at any point previously. Tit for tat action, in the chain of Indian airstrikes and Pakistani counterattacks by missiles, drones and ground troops, threatened to engulf these volatile regional nuclear powers in a deadly race for ascendancy. Thankfully, good sense and effective mediation prevailed. But military action was only part of the threats, posturing and intimidation at the time. Such were India’s national security concerns, on 23 April 2025 it suspended the strategic Indus Waters Treaty.[5] This dramatically decreased water supplies to Pakistan’s vital Chenab River. In response, the authorities in Islamabad, who were already struggling with humanitarian fallout from the war, interpreted India’s action as a provocative ‘act of war’ that worsened an already dangerous situation.[6] Nuclear conflict may have been avoided this time, but the threat has increased.

Third, the recent conflict was ended by effective international pressure and mediation. Left to their own devices, and without an admixture of intimidation and incentivization by outside parties, Pakistan and India might have preferred persisting violence to pursuing peace. Political pragmatism may have also played its part, for conflict costs money, lives and reputations. Early indications are the US-led mediation process, which received strong backing from Saudi Arabia and Turkey, laid the foundation for future talks. Time will tell. Regional stability, in the face of Russian and Chinese expansionism, is not such a hard sell today in Delhi and Islamabad. That said, US President Ronald Reagan’s (1911-2004; Pres. 1981-1989) words still pertain to the on-going crisis in Kashmir: ‘Peace is not the absence of conflict, but the ability to handle conflict by peaceful means.’[7] While territory remains disputed, armed insurgents active, and water resources scarce, war remains an immediate possibility.[8]

How, then, might the cycle of violence and persistence of suspicion be broken? In the first instance, by outsiders understanding more about the ugly history and destructive legacy of conflict that ruins the natural beauty of Kashmir. Why is this important? Because without it, outsider reporting and international involvement will fail to ring true to national and regional leaders, and to implicated locals, in India and Pakistan. Yes, in the end India and Pakistan are going to have to sit down together to hammer out a lasting peace agreement, but outsiders can delay that day by projecting their own perspectives and interests on the dispute and on the pathway to its resolution. Ill-informed meddling invariably increases a mess!

So, what should outsiders know? Three key things, I suggest.

First, the depth and reach of the conflict in Kashmir. As noted already, the most recent outbreak of regional violence belongs to a long history in the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. When added to the new geopolitical profile of India (as an aspirant economic and political superpower) and of Pakistan (as a strategic economic ally of China), the stakes on securing dominance in the region are high: certainly, higher than when Britain, guided by the last Viceroy (and first Governor-General) of India, Lord Louis Mountbatten (1900-1979; Viceroy fr. 20 February 1947; G-G. 15 August 1947 to 21 June 1948) secured Kashmir’s accession to India at the time of Partition (14/15 August 1947). The war which followed (22 October 1947 to 1 January-1949) ended in a UN-brokered ceasefire and creation of the so-called Line of Control (LoC). But peace was short-lived.[9]

A second Kashmiri war broke out in 1965. This ended in a military stalemate and the flimsy Tashkent Agreement (10 January 1966).[10] War erupted briefly once again, but this time more decisively politically, in December 1971, when India supported Bangladesh’s successful bid for independence from Pakistan.[11] As we glimpsed before, renewed resentment, and new grounds to attack India, led Pakistani militants to raid the disputed Kargil District of Ladakh in Kashmir in May 1999. Repulsed by India, Pakistan sued for peace. The result: India regained control of Kargil heights, and a nuclear cataclysm came ever closer, with both countries having successfully detonated nuclear devices in 1998.[12]

Since 1999, border clashes, proxy wars and terrorism have continued. In 2001-2 a tense stand-off followed attacks by Pakistani militants on the Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly (1 October 2001) in which 38 people were killed, and on the Indian Parliament (13 December 2001) in which 12 people were killed including the 5 terrorists.[13] From 26 to 29 November 2008, 10 members of the militant Islamist group Lashkar-e-Taiba wreaked havoc in orchestrated shootings and bombings in Mumbai: 175 people were killed (including 9 of the attackers) and 300 were injured. On 28-29 September 2016, teams of Indian Army Para breached the heavily militarized LoC in response to the killing of 19 Indian soldiers by 4 members of Jaish-e-Mohammed in Uri, India. On 26 February 2019, the Indian Air Force made a ‘surgical strike’ on a (supposed) training camp for Jaish-e-Mohammed in Balakot, Pakistan. As on other occasions, justification for India’s actions and Pakistan’s response were (to international observers) both suspicious and politicized. Indo-Pakistan relations are not only about Kashmir, but the deep-seated regional dispute creates a highly volatile context, as recent events confirm.

Second, conflict in and over Kashmir has become, over time, much more than a territorial dispute. It has become a symbol of contrasting – and competing – national identities. Partition saw a majority of Indian Muslims driven to join their religious neighbours in the newly created country of Pakistan. Historic accommodation in multi-cultural India was subsumed in religious violence and nascent nationalism. Since 1947, the lines of national and ideological difference have deepened with militant, religious extremism polarizing both countries nationally and internationally.[14] Kashmir has become a lightning rod for passionate nationalism and religious ideology. To the powers that be in New Delhi, Kashmir is about India’s sovereignty, security, global status and constitutional ‘secularism’. In Islamabad and villages across Pakistan, Kashmir is a symbol of the injustice of Partition, of the importance of Islamic integrity, and of an ancient, rural, way of life under threat from modernity. After the 2019 repeal of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which had hitherto accorded Jammu and Kashmir special status as an Indian state (with its own Constitution, flag, administration, laws and rights to residence and property), two union territories of Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh, were declared. This provocative action increased regional tension, eroded the little trust many Kashmiris had in the Indian government, and opened the door to pro-Indian political bias, human rights violations, and security crackdowns. The case for militancy increased: incidents of Pakistani-backed cross-border raids multiplied.[15] The 2025 Pahalgam attack confirms again how deep the distrust and near the conflict in the region. Failure to establish, and maintain, effective mechanisms to safeguard peace exposes both countries to on-going risks. More than this, until issues of self-determination, human security, and regional diplomacy are comprehensively addressed, Kashmir poses an on-going existential threat to SE Asia and beyond.[16]

Drilling down into conflict in and over Kashmir, two other issues stand out for brief comment.

First, water security. The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed between India and Pakistan in 1960, is often cited as an example of the two countries’ capacity to cooperate, despite their violent disagreement over Kashmir. If this was once true, it is no longer. Indeed, water security has become one of the most contentious issues in their cross-border territorial dispute. Climate change has expedited glacial melt and disrupted monsoon patterns. As a result, both nations face increased water insecurity. Shared rivers have become a flashpoint for conflict.[17] The IWT allocated Pakistan a significant share of rivers in the West of the country. It now faces Indian hydroelectric projects upstream that threaten water supplies in Pakistan. Though the IWT included mechanisms to resolve disputes, legal challenges and international arbitration have fostered an increased sense of mutual distrust and fear of water poverty. Inflammatory language and a weaponizing of water have politicized the issue in both countries and further compromised goodwill. Though still recognized, the IWT has become a symbol of conflict. Water has become a zero-sum option, and conflict displaced cooperation as the default position.[18]

Second, cross-border insurgency and insecurity. The persistent threat of cross-border militancy fuels ongoing tension between India and Pakistan and undermines national security in both countries. Pakistan is accused of abetting cross-border attacks, such as those on Mumbai in 2008 and on the Indian army base near Uri, in Jammu and Kashmir, in September 2016.[19] Pakistan refutes these claims, citing the unresolved nature of the Kashmir dispute as inherently provocative. Violence, nationalism, securitization, militarization, infiltration and cease-fire violations conspire to fuel animosity and erode trust on both sides of the border. Lack of a sustained, structured engagement with the root causes of militancy – coupled with inflammatory political rhetoric and ill-informed popular sentiment – makes resolution of the conflict both elusive and improbable. India and Pakistan continue to present cross-border militancy in terms of blame, accusation and retaliation. Peace will remain a distant ideal while trust and a will to concede and cooperate are absent.[20]

Practical policy proposals

Read in this light, how might the conflict over Kashmir be resolved? This is not an easy question to answer. In what follows, I propose five practical steps policymakers inside and outside India and Pakistan might consider. None of these steps are straightforward. All of them depend ultimately on subordinating short-term political and military ‘wins’ to long-term socio-economic and diplomatic ‘benefits’. Negotiation may have failed hitherto: it should not be assumed it can never succeed if the terms and incentives for agreement are clearly presented.

i. International diplomacy

As noted above, the recent military confrontation between India and Pakistan was ended by an internationally brokered ceasefire. Opposition to the conflict (and fear it might escalate) brought together the US, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and a range of regional partners. The strength, and future potential, of multilateral diplomacy was clear. An inclusive diplomatic alliance is crucial for a long-term solution to Kashmir. China’s role in this should not be underestimated: it has strong economic and political ties with India and Pakistan and can act to leverage (or incentivize?) agreement. But a lasting peace will also depend on an open, structured dialogue that is carefully monitored by outside parties: this can serve to pressure India and Pakistan to agree and to keep their word. Timelines, progress markers, facilitated dialogue and in camera conversations, will all be needed. The UN and SCO suggest themselves as suitable venues for safe, discreet, and potentially prolonged, negotiation.

ii. Updating the IWT

Water is a source of conflict around the world. This should not be so. As we have seen, it features increasingly in Indo-Pakistani relations. Urgent action is needed to revisit and revitalize the Indus Waters Treaty. The IWT is still a symbol of humanitarian cooperation that traces its source to the moral headwaters of mutual respect and a common humanity. Climate change and new geophysical realities demand a renegotiation of the IWT. Given the history of conflict over Kashmir, renegotiation might require an interested third-party to encourage dialogue and enable conflict resolution. The resources and reach of the UN or World Bank could possibly help here to aid transparency and enable a good, equitable solution. Going forward, a monitoring agency to track and trace water use and abuse (i.e. pollution) will also be needed. To prevent violations and promote cooperation, a new IWT would include detailed technical cooperation and data sharing in which the impact of climate change on water quantity and quality could be recorded and reported.

iii. Regional Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs)[21]

The depth of Indo-Pakistani suspicion requires dialogue over Kashmir begins upstream in reconstructing basic lines of communication and reconfirming ground rules of engagement. Confidence building, through a series of carefully orchestrated ‘Confidence Building Measures’, is a sine qua non of progressing international dialogue. To penetrate the meniscus of threat, fear and intimidation, early attention should be given to back-channel talks, dialogue between military leaders, and greater openness on nuclear safeguards and troop movements in sensitive areas. Funding for academic exchanges, together with shared cultural and environmental projects, could also nurture mutual understanding as a basis for reduced tension and durable peace. Shared ecological concerns naturally feed into an Indo-Pakistani Commission on environmental issues. Water security and disaster relief could yet emerge again as symbols of international collaboration.

iv. International development and humanitarian relief

Decades of conflict have had a catastrophic impact on Kashmir and along the ‘Line of Control’ (LoC). It will take time and considerable investment to create sustainable economic development and communal flourishing. The lives and livelihoods of individuals and institutions on both sides of the border require tangible improvement/s. To achieve this, India and Pakistan need international help, and, crucially, the political and regional will internally to receive it. Development expertise and substantial international funding to address short-, medium- and long-term impacts of conflict, displacement, multi-generational impoverishment (of every kind), and the physical, emotional and relational damage associated with long-term conflict, are urgently needed. As in other war zones, healthcare, education and professional development in Kashmir have fallen far behind urban centres in India and Pakistan. Enlightened investors, international NGOs, and major corporations will all have a role to play if Kashmir is to recover its confidence in the possibility and potential of peace. The benefit globally? Nothing less than a reduction of the threat of nuclear conflict in SE Asia.

v. Collaboration on counterterrorism

Renegade militants plague contemporary geopolitics and regional harmony on the border between India and Pakistan. In addressing the on-going conflict in and over Kashmir, India and Pakistan should commit to strong, official systems of intelligence sharing, and cooperate to fight terrorism. They do not need to address this alone: International organizations, such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and UN Office of Counterterrorism, are committed, and commissioned, to address this problem globally. Both offer technical support, coordination, and robust accountability mechanisms. A joint counterterrorism task force, supported internationally and with independent oversight, will help to depoliticize cooperation and target non-state threats to regional peace. The danger Kashmir poses is, as ever, greater than geography and diplomacy may suggest, viz. it feeds and fires copycat action to destabilize and destroy accredited systems of government, control and arbitration.

Conclusion

The May 2025 ceasefire between India and Pakistan represents a significant shift in policy over the Kashmir dispute. America’s involvement in particular – motivated in part, surely, by its attentiveness to China’s economic imperialism worldwide – gave weight to peace initiatives some would otherwise have suspected. Through US actions more serious conflict and consequences were averted. Diplomacy and dialogue, together with behind-the-scenes incentivization and negotiation, helped to de-escalate the situation rapidly. However, the resultant peace remains tentative and vulnerable, without sustained political resolve to tackle the underlying issues of territory, militancy and water. Given its history and on-going involvement in the region, it behooves the US to continue to support dialogue, to promote trust, and to press for long-term terms solutions to current problems. But peace in South Asia is ultimately a multi-national matter. In pursuit of peace, international action should always prefer diplomacy to deterrence, dialogue to direct action.

Iram Naseer Ahmad – Oxford House Research Associate[22]

As in all Oxford House Briefings, every effort is made to attribute images where information is available.

[1] For a substantial study, see V. Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War (I.B. Tauris, 2010).

[2] Y. Zhang, ‘Calm along India and Pakistan Borders as Truce Holds’, China Daily (Beijing, 2025): https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202505/13/WS6822aee8a310a04af22bef61.html.

[3] O-A. Cleary, ‘India and Pakistan Cease-Fire Appears to Hold Despite Accusations of Violations’,” Time Magazine (Lahore, 2025): https://time.com/7284654/india-pakistan-ceasefire-trump-us-mediation-kashmir-conflict-strikes.

[4] L. Shan, ‘India Launches Military Strikes Against Pakistan’, Wall Street Journal Asia (7 May 2025): https://www.wsj.com/world/asia/india-retaliates-for-attack-in-kashmir-it-blames-on-pakistan-3aea5ac4.

[5] J. A. Mirza, ‘A War Nobody Wins: The Real Cost of India-Pakistan Rivalry’, The Diplomat (May 2025): https://thediplomat.com/2025/05/a-war-nobody-wins-the-real-cost-of-india-pakistan-rivalry/.

[6] Y. Sharma, ‘”No Guardrails”: How India-Pakistan Combat Obliterated Old Red Lines’, Al Jazeera (Doha, 2025): https://thediplomat.com/2025/05/a-war-nobody-wins-the-real-cost-of-india-pakistan-rivalry.

[7] D. Carleton and M. Stohl, ‘The Foreign Policy of Human Rights: Rhetoric and Reality from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan’, Human Rights Quarterly 7 (1985): 205.

[8] K. B. Pragati and A. Das, ‘How India’s Threat to Block Rivers Could Devastate Pakistan’, The New York Times (2025): https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/24/world/asia/india-pakistan-indus-waters-treaty.html.

[9] Cf. S. Ganguly, Conflict Unending: India-Pakistan Tensions since 1947 (Columbia UP, 2002).

[10] Cf. F. N. Bajwa, From Kutch to Tashkent: The Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 (Pentagon Press, 2014).

[11] Cf. S. Bose, Dead Reckoning (Hachette, India, 2012).

[12] Cf. J. Singh, Kargil 1999: Pakistan’s Fourth War for Kashmir (Knowledge World, 1999).

[13] The identity of the militants is disputed. Pakistan rejects India’s claim they were members of two ISI-backed militant groups in Jammu-Kashmir, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed.

[14] R. G. Wirsing, ‘The Kashmir Territorial Dispute: The Indus Runs through It’, Brown Journal of World Affairs 15.1 (2008): 225-40.

[15] M. Waqas and K. Rehman, ‘The Kashmir Dispute: A Strategic Analysis’, VFAST Transactions on Education and Social Sciences 11.3 (2023): 17-23.

[16] Cf. Mirza, ‘A War Nobody Wins: The Real Cost of India-Pakistan Rivalry’.

[17] Cf. Sharma, ‘”No Guardrails”: How India-Pakistan Combat Obliterated Old Red Lines’.

[18] Cf. Das, ‘How India’s Threat to Block Rivers Could Devastate Pakistan’.

[19] On 18 September 2016 four militants from Jaish-e-Mohammed attacked an Indian Army brigade headquarters near Uri. 19 Indian soldiers were killed in the attack, and more than 20 injured. Cf. A. Ahmed, ‘Uri Attack and the Doval Doctrine’, Defence Journal 20.3 (2016): 13.

[20] V. Sharma, ‘Coercive Diplomacy: The India-Pakistan Case’, International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation 9.1 (2022): 19-25.

[21] This is an important, much-discussed theme. In addition to work by the Stimson Center in Washington, DC., see, e.g., R.W. French, ‘Constructing Cooperation: A New Approach to Confidence Building between India and Pakistan’, The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs and Policy Studies 108 (2019): 121-144: https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2019.1591767; Y. A. Sheikh, ‘The Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) between India and Pakistan’, Journal of Islamic World and Politics 7.1 (2023): https://doi.org/10.18196/jiwp.v7i1.46; M. W. Haider and T. M. Azad, ‘The role of confidence-building measures in the evolution of relations between Pakistan and India’, World Affairs 184.3 (2021): 294-317: https://doi.org/10.1177/00438200211030222.

[22] The writer is Assistant Professor at Forman Christian University, working in the Department of History and Pakistani Studies, a Research Associate of Oxford House (www.oxfordhouseresearch.com) and has a History PhD from the University of the Punjab.