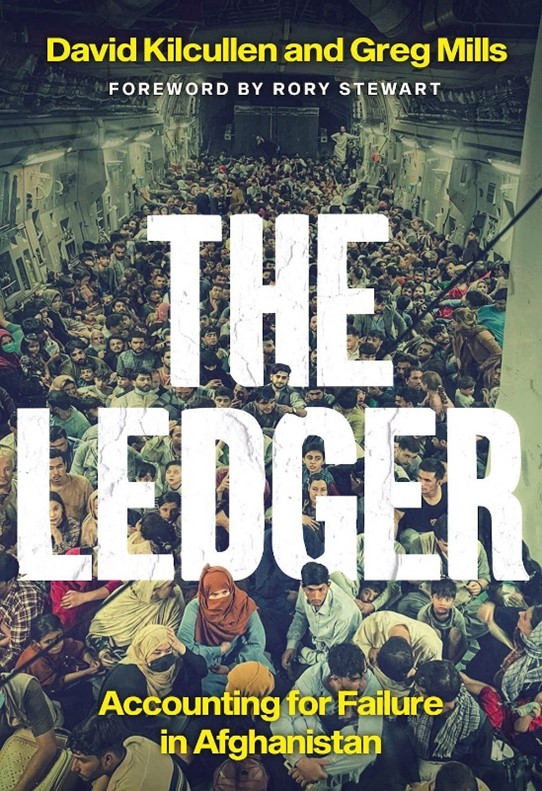

Review by Major General Rob Thomson, CBE, DSO: David Kilcullen & Greg Mills (With a Foreword by Rory Stewart), The Ledger – Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan (Hurst Publishers, 2021), pp. 368.

I am delighted to be able to post this fine review by my good friend and Senior Associate of Oxford House, former Major General Rob Thomson, CBE, DSO. Rob is a person of immense courage and integrity. I count his assessment – and commendation – of Mills and Kilcullen’s book a significant addition to Oxford House’s work on culture, ethics and religion in contemporary geopolitics.

Plaudits for Drs Greg Mills and David Kilcullen’s The Ledger – Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan (Hurst, 2021), are justified. The Telegraph’s ‘Best Book of the Year 2022’, The Ledger is, indeed, ‘a clear-eyed analysis’ by two insiders on how the war in Afghanistan ‘was lost when it could have been won’ (Sunday Times). As General Mohammad Yasin Zia, former Chief of the General Staff in Afghanistan, says of Mills and Kilcullen’s book, ‘This explanation of the failure of the international mission and fall of Kabul contains salient lessons for us all, now and in the future.’ The former Chief of the Defence Staff in the UK, General Sir Nick Carter, is equally warm in his praise: ‘What went wrong and what went right in Afghanistan? This brilliant analysis by two people who were there has many of the answers.’

So, what does The Ledger tell us and what lessons should the world learn?

Professor Christopher Hancock

*********************************

Twenty years after arriving in Kabul in pursuit of the Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, the US-led coalition departed. Afghanistan and its war-weary people were left in the hands of the Taleban, amid heart-breaking scenes of desperation outside and within Kabul airport. Those images remain all too clear in many minds, not least, those of the Afghans who had hoped for so much better from the Western military presence in their country. Here are memories which have, without doubt, done immense damage to the credibility of the West, to its ways, and even, very sadly, to its values.

What is less well known – and recognising that many geo-political comparisons are invidious and quite often flawed – is that 2024 was also the 60th anniversary of the UN Peace-Keeping Mission in Cyprus: there have never been nor are there plans to leave.

It seems that Western stamina is not what it was.

The collective failure to demonstrate stamina is all too clear from the very beginning of The Ledger. Quick to the printers, this book appeared in the very year Afghanistan was abandoned. It is a reasoned, heart-breaking and uncompromising book by two academic practitioners (or better, perhaps, practising academics!), who know Afghanistan far better than anyone else of their cohort: they know what they are talking about. There is honesty in what they write, and courage in the way they conducted themselves in Afghanistan. Greg Mills’ fact-finding mission in a fuel truck to Spin Boldak on the border with Pakistan, undertaken in order to understand first-hand how personal and institutional corruption was undermining the security, economy and governance of Afghanistan all at the same time, was courageous, if not a touch foolhardy. His journey revealed the scale of the challenge faced, in country and in the region.

Mills and Kilcullen’s particular skill – which makes the book so readable and important – is in blending national, regional and international analysis with a critical reflection on the failure of the Afghan campaign. Here is an utterly convincing, punishing assessment of a chapter in Western and Asian history from which many lessons must be learned.

But I was also hugely impressed by the way the authors of The Ledger don’t, and won’t, duck personal complicity. There is moral courage to match their physical courage. As an officer who served in Afghanistan for a total of 18 months, the book confronted me, too.

I remember on my first tour of Afghanistan in 2009 being quite proud of the growth in business in Sangin market (our predecessors and successors deserve equal credit) but getting very exercised by the lack of peripatetic judges coming from Kabul – and my inability to make it happen. Instead, justice was being done and seen to be done by the Taleban in our town, which gave them control and a frustrating local legitimacy. Despite pleas, the judges never came from Kabul in my day. When I went back in 2014, the answers to my questions around extending the Kabul legal writ into Sangin were sadly opaque. Had I pushed hard enough?

Strong on IQ and EQ, The Ledger provides cool-headed analysis of how and why the coalition failed collectively and comprehensively in Afghanistan – a failure which was and remains international, regional, national, provincial and local in character. The pain for those who served there, lost colleagues there, and yet came to love the country and its people, is that the far greater pain and cruel legacy of the conflict is being felt by the ordinary men, and especially women, of Afghanistan, many of whom suffered as we did, but who today feel abandoned and betrayed.

The book also offers prognoses, none of them easy or short term. But that is the way of nation-building and counter-insurgency. All the lessons drawn out deserve notice. The do’s and don’ts of the book’s penultimate chapter deserve a place near the desk of every politician, diplomat, development worker, and soldier as they reflect on the Afghan campaign and contemplate future operations. Wisdom learns lessons. The Ledger’s assessment deserves to be read, flagged, underlined, refined, debated and widely shared.

Mills and Kilcullen paint with wisdom and clarity the gap between western ambitions and our achievements. I was struck again and again in succeeding chapters by the West’s lack of collective humility: excluding the Afghan government from the negotiations with the Taleban; aspiring to our forms of government; and, perhaps most strikingly for this soldier, diverting from Afghanistan, conceptually and physically, to Iraq not two years after the Taleban fell from power in 2001 and while a new government was still in its infancy.

Mills and Kilcullen also trace a series of missed opportunities. With the Taleban on the run in 2001, there was huge opportunity to negotiate a political settlement from a position of (relative) strength – a loose accommodation, one which was Afghan in nature and character. Two decades later, a peace agreement, hastily cobbled together as a face-saving means of justifying withdrawal, was not the answer.

There was perhaps a second opportunity, highlighted in the book: probably and sadly beyond the political appetite of the day. An enduring presence, strong conceptually and light physically, could have sustained, for a relatively light premium, the Ghani government and supported the Afghan National Security Forces. A limited set of specialist capabilities and skills, tailored to Afghan needs, could have been a low risk, small premium that would have showed western stamina and could have shifted the balance away from the Taleban and in favour of the Afghan government.

Mills and Kilcullen also extrapolate lessons for the wider world from Afghanistan. In particular, they cast their eye West-South-West. Africa, perhaps the forgotten continent of our age, offers no shortage of challenges as its population explodes out of all proportion to its economic growth, and Africans, with the most limited of opportunities, confront a future where the wealth gap (in-country and beyond the continent) nurtures potentially explosive radicalism and impoverishment. But there are opportunities: the authors’ deep dive into Somaliland, and its very local approach to solutions, allows one to close The Ledger with some hope.

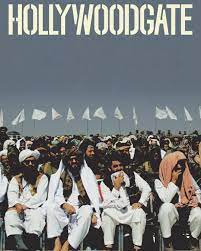

I end with one final, personal, reflection. As I was reading the book, I happened to watch Hollywoodgate (2023). It is a powerful, brilliant even, fly-on-the-wall documentary about the Taleban in the aftermath of the US and Coalition withdrawal from Afganistan in 2021. It was made and produced by the young Egyptian film-maker, Ibrahim Nash’at.

Admitted by the Taleban to film their new Head of the Air Force, we get neither the film the Director wanted to deliver nor the film the Taleban wanted to be made. The film hovers tantalisingly in a grey zone as a mostly unspoken battle of wills between the new Taleban Head of their Air Force and the filmmaker unfolds. The threats, both those uttered and those left unsaid, are chilling. ‘That little devil is filming again,’ one mutters when Nash’at comes close. ‘If the director misbehaves,’ says another, ‘he will promptly be taken outside and killed.’

It is clear that one year on from seizing power, the Taleban want a fly-past to adorn their military parade at Bagram (where they will show off the equipment abandoned by the West and which they have turned to their own purposes). So, they re-call the former pilots from the Afghan Air Force, who line up in the new Head of the Air Force’s office, not knowing what is to befall them. Those pilots aspire to courage, that is evident to the camera, but an understandable and underlying anxiety is clearly visible in their faces. For me, it underlined the all too painful very personal consequences of our departure, so evident in the pages of The Ledger.

Rob Thomson, Senior Associate

As in all Oxford House Briefings, every effort is made to attribute images where information is available.