It may be that Oxford is landlocked and I am just back from a peaceful break on the beautiful Pembrokeshire coast in SW Wales, but the sea has been much in mind in the last few days. With its awesome power and spine-chilling way of stilling a soul as it crashes on pebbly shores and of stirring emotion in a terrifying calm, it is little wonder artists and poets, novelists and advertising agencies, have looked to the sea for ideas and inspiration. Having spent many years aboard the famous training vessel HMS Conway, the English Poet Laureate John Masefield (1878-1967) knew what he was talking about – and feeling – when he penned his famous poem ‘Sea-Fever’ (1902):

I must down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking.

I must down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.

(Photograph: The Gallery Collection/Corbis)

The magical, mystical, magnificent allure of the sea. I can almost smell the salt air and feel the bracing spray, as I write! Yes, it may be in Masefield’s terms ‘a clear call’ that draws a person to the sea: it is also ‘a wild call’, for woe betide those who claim to tame the cruel sea.

(Photograph: Royal Library, Windsor)

As artists and authors have shown, there are many ways to see the sea. In one of his most remarkable flights of artistic and scientific fantasy, the Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) imagined a view of the sea and shore of Italy from the air. In a picture from near the end of his life (ca. 1515) that is part-map part-frieze, the elements of earth and water meet in a natural harmony of curving bays and golden beaches. In contrast, in the work of the German Romantic landscape painter Casper David Friedrich (1774-1840) and his ‘great sea dog’ British contemporary J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), the sea threatens and envelopes, and merges with the sky in a maelstrom of motion, confusion, and mystery. Though esteemed in the modern era, to his skeptical contemporary William Hazlitt (1778-1830) Turner’s seascapes were ‘pictures of nothing, and very like’ (!), while on the streets of Chelsea he was known by his presumed profession as ‘Admiral Puggy Booth’. The sea, it seems, has a way of making fools of all of us – at least, such is one reading of the Japanese artist Hokusai’s (1760-1849) ‘The Great Wave’, in which three small ships are lost before a monstrous wall of water. Who would presume safety amid such primordial chaos? Who claim to chart a course in this fluid elemental state? Extrapolating from this, many have sought to capture in visual and literary form the reality of mankind’s turbulent existence as life at sea, with no lights to guide nor haven or horizon in view. While ‘Empires of the Sea’ have over millennia sought to project temporal power through naval supremacy – as if control of the deep validated their boasting and belief in invincibility – they have, it seems, forgotten how ‘wild’ is ‘the call of the sea’ … and that the sea can make fools of us all. The legendary madness of Danish King Cnut (Canute: d. 1035), ruler of the so-called ‘North Sea Empire’ of England (fr. 1016), Denmark (fr. 1018) and Norway (fr. 1028), who thought his political potency could halt a rising tide, is all too familiar to historians and therapists!

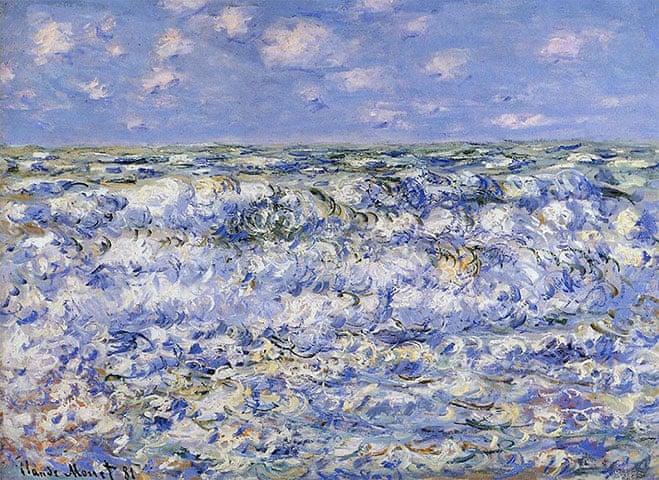

(Photograph: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco CA)

Other artists and authors have taken a different view of the sea. They have projected that other face we know well … and hope for on a beach holiday! That happy lapping of waves on a seashore that Claude Monet (1840-1926) celebrated in many representations of his beloved Normandy coast. Even Monet’s ‘Waves Breaking’ (1881) seems to have a creased smile. And then there’s that deep penetrating stillness that pours through the brush into ‘Sunset’ (ca. 1872) by American luminist John Kensett (1816-1872) and the sliver of sea that creeps across the horizon in David Cox’s evocative holiday painting ‘Rhyl Sands’ (ca. 1854). For the sea isn’t an endless grey, it is also bright and light, a place of sport and play, of fishing and crabbing, of crumbling sandcastles and gritty sandwiches. How sad when this most captivating of waterparks becomes a battleground, when this vast, liberating, public space is packed or privatised by violent pirates and boundary predators, by dirty polluters and shameless profiteers. ‘Twas always thus’, we may be tempted to say: but habit should never determine ethic – in fact, quite the reverse! We can choose how we see and use the sea.

So, what of the five major oceans (Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic and Southern) and myriad integral, separate, or marginal seas (e.g., the Andaman, Amundsen, Arabian, Baltic, Bering, Black, Caribbean, Chilean, Chukchi, Coral, Japan, S. & E. China, Labrador, Mediterranean, North, Okhotsk, Red, Sargasso, Weddell and the Gulfs of Alaska, Mexico and Guinea), that cover ca. 71% of the Earth’s surface and are so full of life, threat, promise and riches? Let me suggest three things, at a time the sea has arguably never been so lively a geopolitical issue. Indeed, for this reason we must, as Masefield says poetically, ‘down to the seas again’.

(Photograph: Tate Images)

First, the sea in all its varied locations and forms is a challenge to reckon with depth in life. Statistics on the Mariana Trench, the largest and deepest area in the Pacific Ocean, leave one breathless: it is ca. 2550 km long, on average 69km wide, in Challenger Deep 10994m (36069 ft) deep, and has water pressure 1086 times that of air pressure at sea level. As Sir David Attenborough’s Blue Planet television series (2001 & 2017) have reminded millions, the sea is a place of extraordinary beauty, mystery, majesty and profundity. To many, it is the Earth’s ‘final frontier’. To treat such with disdain or disregard is to overlook ca. 71% of what Earth may offer! Superficiality sits ill with a student of the sea; or, to put it another way, no serious student of any kind at any stage in life can, or should, not reckon with the elemental ‘call of the sea’ to depth in life.

It is no wonder, perhaps, the sea has been bound up with the great myths and religions of the world for centuries. As Fabio Rambelli points out, for example, in his edited volume The Sea and the Sacred in Japan: Aspects of Maritime Religion’ (Brill, 2018), the sea is central to traditional Japanese religion. Likewise, Iemanjá, the mighty African goddess and guardian of the sea, is honoured on the coast of Brazil by devout Candomblé in a festival that bears her name. So, too, study of the ‘tars’ who manned the ships when Britain ‘ruled the waves’ in the 18th and 19th centuries shows them to have been predictably a-religious in practice but strikingly ‘spiritual’ in outlook. As Marcus Rediker has written of the impact of the rigour and unpredictability of their life at sea, this ‘forcefully affected the seaman’s worldview, intensifying … not his attachment to formal religion but to beliefs and practices frequently denigrated as “superstition.” The tars worldview combined the natural, the supernatural, the magical, and the material’ (Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea [1987], 179). The sea, in short, takes you places you may not expect, or want, to go; to depths in every sense that may be dark but also shine. As in the 1989 film, ‘the abyss’ may radiate unexpected light.

(Photograph: Tate Images)

Second, expanding the last point, the sea affords unique opportunities for self-discovery. In the great ‘Age of Discovery’, explorers of uncharted seas – like da Gama (ca. 1460-1524), Columbus (1451-1506), Magellan (1480-1521) and Raleigh (1552-1618) – were in search of humanity as much as global geography. They wanted to know what humans could find and thereby become. Their generation grasped what many forget, that ‘self’ is more often found in movement than in stasis, in an open quest for truth more than closed self-righteousness or unquestioning rectitude. Those who objectify – or, worse, now weaponize – the sea miss, arguably, the greatest gift it affords, its subjective appeal to common sense and our shared awareness of physical vulnerability. We learn much about ourselves on windswept shores and when tossed about on stormy seas!

(By Source, Fair use)

When applying to Oxford University decades ago, my fine history and philosophy teacher had one piece of advice for me, ‘Read Iris Murdoch’ (1919-1999). He was right. I lived in a small world and needed my horizons broadening. ‘Begin with The Bell (1958)’, he said ‘and then you might try The Nice and the Good (1968)’. Oxford academic philosopher Murdoch’s brilliant fusion of gripping narrative and acute thought prodded me (and any reader, I still think!) to check I was asking enough questions. Murdoch’s Booker Prize winning novel The Sea, The Sea (1978) has had a number of radio adaptations; most recently, a two-part BBC Radio 4 version (2015) starring Jeremy Irons, Maggie Steed and Simon Williams. Echoing a line in French poet Paul Valéry’s (1871-1945) poem Le Cimetière Marin (ET, The Graveyard by the Sea) and the Greek military commander and historian Xenophon’s (ca. 430-354 BCE) record of the shout ‘Thalassa! Thalassa!’ (Lit. The sea! The sea!), that 10,000 hard pressed Greek soldiers gave in 401 BCE (when they glimpsed the Black Sea – and thus life and hope – from Mount Theches in Trebizond), Murdoch sets the relational struggles of the obsessive, self-satisfied, playwright and director Charles Arrowby against the backcloth of an isolated house by a raging sea. One line from Arrowby in this deep, disturbing novel of love, longing, and obsession, stands out: ‘How much, I see as I look back, I read into it all, reading my own dream text and not looking at the reality…’. To Murdoch, as in Valéry’s poem and Xenophon, the repetitive surge of the sea offers a clear view of misguided longing and futile obsession and the hope of new beginnings. ‘Be sensible’, it pleads again and again, ‘Remember the fragility of life.’ Yes, the sea can make fools of us all: it can also make us wise. As Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) says, in his poem ‘Dover Beach’ (ca. 1851), of pebbles that waves ‘draw back, and fling’, ‘At their return, up the high strand, / Begin, and cease, and then again begin’.

(By Wollex, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Last, beneath the surface of the sea lie rocks that shatter secularism and ground faith. There has been much discussion in military and political circles in the last few years of China’s huge investment in its navy, or Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). The precise details of this cannot detain us – nor are they always available to outside observers – but the strength and direction of China’s aspiration to operate as a ‘Blue water’ fleet and to be active both in the South and East China Seas, and more generally to safeguard Chinese shipping and its wider geopolitical interests, attracts commentary and concern from Tokyo to Washington, DC. As Robert B. Murrett wrote earlier this year in the US Military Times (22 March 2021): ‘[T]he growing number of ships and submarines in the PLAN is worthy of our attention, and as they say, quantity has a quality all of its own.’ He continues, ‘[U]nderestimating the steady progress of the Chinese navy would … reflect a serious miscalculation.’ And, exploring weaknesses in PRC’s naval capability and command structure, he points out, ‘[T]he professionalism, consistent at-sea experience, combat readiness, and command and control capabilities of any navy are paramount.’ China is not alone in its historic military commitment to the sea. But Murrett is right, surely, to name the hidden rocks of human fallibility, over confidence, and sheer inexperience, that can ‘hole below the waterline’ even the finest navy. Perhaps, as noted above, it is to those other factors and forces that make the sea, the sea, that the eye of faith will be consistently alert amid the swirling eddies of militarism and secularism. As the Old Testament Psalms reminds the fearful day-tripper and weathered ‘tar’, ‘Mightier than the thunder of the great waters, mightier than the breakers of the sea, the Lord on High is mighty’ (Psalm 93.4). This is the perspective all-too familiar to – and respected by – sailors of old: ‘Look to the heavens to keep on course.’ Or, as the poet John Masefield might put it, here is ‘a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied’.

Christopher Hancock, Director