This is my second ‘Briefing’ for Oxford House on the military conflict and humanitarian crisis that is consuming Ethiopia, particularly the rugged northern district of Tigray. To recap. Years of growing political and military tension led to a confrontation between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) – which dominated Ethiopian politics for almost thirty years – and the Prosperity Party, a new coalition that supports the Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (b. 1976; PM 2 April 2018 – present). The Ethiopian leader was supported by neighbouring Eritrea and some Somali soldiers. On the night of 3-4 November 2020 troops of the Tigrayan regional government (Tigray Defence Forces or TDF) were involved in clashes with the Ethiopian army’s Northern Command, based in the Tigrayan capital, Mekelle and along the Tigrayan border with Eritrea. This led to a full-scale war, with the TDF engaging the Ethiopian Defence Forces (ENDF), Eritreans, Somalis and militia allied to the Amhara ethnic group. Within weeks the TDF was forced out of Mekelle. This was followed, in late 2020, by a spate of extrajudicial killings, numerous reports of rape and pillage (mostly by the invading forces). Telecommunications and banking in the region were severed, and relief supplies withheld. The way was open for the humanitarian crisis which now overshadows life in Ethiopia and Tigray.

(World/The Times)

Six weeks on from my last Briefing, ‘War in Tigray: when words are not enough…’ (June 14: www.oxfordhouseresearch.com), scraps of news and crackling telephone calls from friends and contacts on the ground, suggest the situation has changed substantially. A significant offensive by the TDF was launched four days after my last piece (18 June). To the astonishment of most observers, over the next few days, the TDF drove Ethiopian and Eritrean forces from town after town in Tigray and its border region. On 28 June, the TDF took the strategic, regional capital of Mekelle. Ethiopian forces were routed, but not before ransacking UN offices and raiding local banks. It is estimated 6,600 Ethiopian troops were captured, with many more killed or wounded.[1] In just ten days, Tigrayan forces gained the advantage and inflicted a heavy blow on their enemies, but, in the process, sustained heavy losses.[2] Jubilation greeted them when they entered Mekelle.[3] Captured ENDF troops were paraded along crowded streets, amid jeers and catcalls, on their way to prisoner of war camps.

So much – too much – of this tragedy remains shrouded in mystery and cloaked in the silent suffering of the innocent, or the protracted anger and shame of countless victims of ethnically motivated torture and rape. The TDF’s latest campaign may have been a military success: it has done little to alleviate human suffering, since Tigray is still largely isolated from the outside world. Starvation is rampant, desperation endemic, mutual hatred tangible. As the Ethiopian military has crumbled, Prime Minister Abiy has turned to the nation’s regions and ethnic groups, with ethnic militia and raw recruits flooding towards the battlefields.[4]

(World News/Sky)

To explain something of the complex politics of the region. The TDF answers to the government of the Tigray region, elected (overwhelmingly) in September 2020.[5] The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) is the dominant force in the region. On 1 May 2021, TPLF and Shene (the Oromo Liberation Army) were designated ‘terrorist organisations’ by the government in Addis Ababa.[6] The Prime Minister and Council of Ministers cited a three-year campaign of attacks on civilians, purportedly ‘to reverse the reforms that have taken place through the demands and struggles of the Ethiopian people for democracy and human rights’. The formal proscription was very clear: ‘These attacks have been perpetrated against innocent civilians and through the destruction of public infrastructure for political purposes and to achieve political goals or objectives.’ It also claimed that behind these attacks are (unspecified) ‘groups’ who orchestrate, fund, inspire, train and provide media coverage, and (unnamed) ‘foreign forces who seek to weaken, disrupt and dismantle Ethiopia.’ The problem for outside observers – and the government of PM Abiy – is that, since the war began, small (and previously insignificant) opposition groups in Tigray have joined the TPLF, transforming local leaders into ‘a government of national unity’ tasked to confront Ethiopian and Eritrean forces, and oust allied ethnic militia. Contradictory commentary and perception have made the conflict in Tigray seemingly intractable.

So, what’s really been going on? It is a confused and confusing situation. Four key things stand out initially.

First, the recent military successes of the TDF have been – at least in part – inspired by Tigrayan revulsion at the weaponizing of mass rape of women and girls by Ethiopian – and, perhaps especially, Eritrean – troops. Women interviewed report joining the TDF, and willingly risking their life every day, as a lesser evil to sexual abuse and gang rape.[7] War is cruel. This act of barbarity scars individuals and families for generations.

Second, the Tigrayans have been fighting on terrain, and in conditions, they know well. This local knowledge, combined with surprise attacks on supply lines and outposts, has sapped their enemy’s energy and eroded its morale. The success of ‘Operation Alula’, as the Tigrayans call their recent offensive, harks back to the guerrilla tactics they refined in their Soviet backed war against the Ethiopian government in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

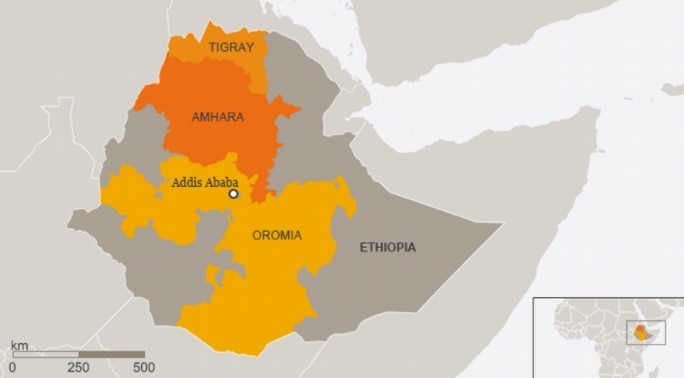

Third, the TDF have had to be proactive: they have no external supply lines. The capture of Mekelle would, and could, never be the end of their advance. The only equipment and ammunition they have was captured in the November 3/4 attack, or been gathered on battlefields since. The TDF could not just ‘dig in’ and consolidate their position. They had to press on – as they did after taking Mekelle – into Amhara and southern Tigray, attacking Ethiopian military positions and requisitioning supplies along the way. In the course of their advance, they crossed the Tekezé, a traditional ethnic boundary.[8] Fleeing Ethiopian troops destroyed a key bridge across the river, to hinder supplies, weapons and humanitarian aid reaching Tigray.[9] The Tigrayans’ slender supply lines vanished.

Fourth, and here you can begin to see how conflict spreads and becomes intractable, casualties among Ethiopian (and Eritrean) troops forced Prime Minister Abiy to seek help from ethnic militia. Over the months, they have become integral to the conflict militarily and politically: crucially, they have turned a localised, civil war into diffuse, ethnic violence. Abiy first used ethnic militia (Amhara Special Forces) in conflict around Humera on the Sudanese-Eritrean border. By late June 2021, he was conscripting troops from regions with many Somali, Oromo and Sidamo.[10] He has paid a high price for these recruits: the war in Tigray has become all-out ethnic conflict. Tigrayans across Ethiopia are footing the bill. When Ethiopian forces were driven from (parts of) Tigray, Amnesty International reported, Tigrayans around Addis Ababa were subject to summary arrest and detention.

In the last two weeks, the situation has changed once again militarily. On 17 July, the TDF’s new campaign turned eastward into the Afar region.[11] There they confronted Ethiopian units, local Afar troops and Oromo militia. Getachew Reda, a spokesman for the Tigrayan forces, said of this recent initiative: ‘We are not interested in any territorial gains … we are more interested in degrading the enemy’s fighting capability.’ Speaking on a satellite phone, he said Tigrayan forces had repelled militia from Oromiya sent to fight alongside Afar troops. It soon became clear, the TDF’s real prize was to sever the road link between Ethiopia, Djibouti, and the sea.[12] If this were to happen, the impact on Ethiopia, and on Addis Ababa in particular, would be both immense and immediate. Imports of every kind, including fuel for public transport and the military, would be hit. Addis Ababa would be dependent on supplies from the South; that is, along the arduous and expensive Kenyan route. Action in Afar could have wide-ranging consequences. Aware of just how crucial this situation is, PM Abiy has deployed much of the remaining ENDF to Afar, leaving other areas open to attack. In the last few days, the TDF have advanced southwards from Tigray, attacking positions in the Amhara region. The ancient Amhara city of Gondar looks dangerously isolated.[13]

There are two other key things to bear in mind about this stage in the war in Tigray.

First, Ethiopia’s economy is struggling. As a recent report in The Economist stated:

Eyob Tolina, Ethiopia’s finance minister, estimates that the price of repairing damaged infrastructure will be around $1bn (about 1% of GDP). Schools, universities and hospitals have been looted or destroyed, as have farms and factories. The government has asked the IMF and the World Bank to bail it out. In February it said it would apply for debt relief under a programme aimed at helping poor countries affected by Covid-19. Rating agencies duly downgraded Ethiopia’s debt.[14]

Others put the cost at nearer $2.5 bn.[15] At the recent G20 Finance Ministers’ meeting in Venice (10 July) Ethiopia’s debt was on the agenda: they will discuss it again in October, when they gather in Washington DC for annual meetings of the World Bank and the IMF. Ethiopia is one of the first countries to ask for its debt to be renegotiated according to the Common Framework adopted by the G20 in October 2020. The framework obliges creditors to negotiate even if they are not members of the ‘Paris Club’ (the agency estd. in 1956, that coordinates major state credit for struggling economies). In this instance, much of Ethiopia’s debt is held by China, whose attitude and actions may prove decisive.

Second, Tigray remains a humanitarian disaster. The 19 July 2021 bulletin of the UN Office for the Co-Ordination of Humanitarian Affairs called it ‘alarmingly dire’, with the possibility of further deterioration ‘if immediate action is not taken’.[16] According to this UN agency, 5.2m. people are in need. Most (75%) live in areas accessible to aid agencies (N.B. this compares with 30% in May), but the flow of aid is (being) severely disrupted by broken bridges and by administrative and military restrictions. A convoy of 54 trucks reached Mekelle on 12 July: the first to do so for two weeks. This is far from sufficient. The World Food Programme says it will run out of food stocks in Tigray this Friday.[17] ‘It takes 100 trucks per day to reach everyone we are aiming to feed. 170 trucks bound for Tigray with food and other supplies are stuck right now in Afar and can’t leave. These trucks must be allowed to move NOW. People are starving,’ tweeted David Beesley, Executive Director of the WFP.

The good news is, after flights were halted on 24 June, the UN Humanitarian Air Service resumed flights into Mekelle on 22 July, bringing key aid workers into the region. But scarcity and a growing risk of famine are present realities in Tigray. Mekelle University issued a press release on 20 July, which underlined the severity of the situation: its bank account was blocked, its budget held back by the federal government, food supplies at universities in Adigrat and Raya would run out by 27 July. Federal authorities were warned that if money failed to arrive by then, the university would ‘not be able to take responsibility for the students’. ‘Collateral’ is a weak word for such callous inhumanity.

The war in Tigray has reached, it seems, a critical juncture: much hangs on whether the TDF can cut the communication links between Addis Ababa and the port of Djibouti, or if it can press on and capture the Amhara heartlands. If their offensive succeeds, pressure on the Prime Minister to negotiate will be immense. There are already stirrings in the army, with the Chief of General Staff, Lt. Gen. Birhanu Jula Gelalcha, hinting at times he is ready to consider negotiating with TPLF.[18] Of course, the Tigrayans might try to launch an offensive westward to create a pathway to supplies through Sudan, but they know this route is heavily defended by Ethiopian and Eritrean forces and would not be easy. Meanwhile, the international community has continued to voice concerns, with Ethiopia subject to (light) sanctions by the US and EU and Eritrea consigned to diplomatic isolation. Annette Weber, new EU Special Representative (until recently with Berghof Foundation) visited Mekelle and floated a suggestion of mediation with the Tigrayan leadership. They reacted coolly – insisting on tough terms before talks begin. As yet, there seems little real appetite in Addis Ababa to negotiate with the Tigrayan authorities: without this, continuation of the conflict seems inevitable, and the suffering of Tigrayans, Ethiopians and the whole Horn of Africa, unavoidable. Is that really the best way to run a world?

Martin Plaut, Guest Author

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/11/world/africa/tigray-guerrilla-fighers-ethiopia-army.html

[2] https://www.liberation.fr/international/afrique/ethiopie-alula-loperation-militaire-qui-a-soudain-fait-basculer-la-guerre-au-tigre-20210629_IJCIMWYERNCI7K6S2FZH3XA6JE/

[3] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/mekelle-under-our-control-spokesperson-tigrays-former-rulers-says-2021-06-28/

[4] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-57818673

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Tigray_regional_election

[6] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/5/1/ethiopia-to-designate-tplf-olf-shene-as-terror-groups

[7] https://apnews.com/article/africa-government-and-politics-united-nations-ethiopia-f834ca1ba251dab58cdbf6b3cd0a038a

[8] https://borkena.com/2021/07/01/tekeze-river-bridge-linking-tigray-amhara-destroyed-report/

[9] https://apnews.com/article/ethiopia-africa-f3d493256f4196c07f5e72e845ec0a29

[10] https://www.voanews.com/africa/observers-worry-tigray-fighting-shifting-ethnic-conflict

[11] https://edition.cnn.com/2021/07/20/africa/ethiopia-tigray-forces-afar-region-intl/index.html

[12] https://twitter.com/KjetilTronvoll/status/1417430146160775205?s=20

[13] https://twitter.com/martinplaut/status/1420383182566871044?s=20

[14] https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2021/04/15/the-war-in-tigray-is-taking-a-frightful-human-toll

[15] https://www.aljazeera.com/program/counting-the-cost/2021/7/17/how-the-conflict-in-tigray-is-fraying-ethiopias-finances

[16] https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/ethiopia/

[17] https://twitter.com/WFPChief/status/1419956551868108800?s=20

[18] https://twitter.com/martinplaut/status/1417889797125849090?s=20