(By Source (WP:NFCC#4), Fair use)

Let’s be honest, alliteration – or the deliberate use of repetitive sounds, syllables and words (even if spelled differently) – can be a wretched thing! Like many people of my age, I grew up with the frightful ‘She sells seashells on the seashore’ and so was pleased to find this engaging alternative on the BBC ‘Bitesize’ channel for children, ‘Sammy the slippery snake came sliding’. The English aren’t alone in their penchant for alliteration. French vire-langues (tongue-twisters) with multiple alliterations (and minimal meaning!) abound. What about, for example, ‘Les chaussettes de l’archiduchesse sont-elles sèches? Archi-sèches?’ [Are the archduchess’s socks dry? Really dry?]; or perhaps, ‘Ce ver vert sévère sait verser ses verres verts’ [This strict green worm knows how to pour his green glasses]; or, even, ‘Je veux et j’exige d’exquises excuses du juge. Du juge, j’exige et je veux d’exquises excuses’ [I want and demand exquisite excuses from the judge. From the judge, I want and demand exquisite excuses]; and then there is always the more profound, ‘Je suis ce que je suis, et si je suis ce que je suis, qu’est-ce que je suis?’ [I am what I am, and if I am what I am, what am I?]! Words and sounds with rhythm and rhyme to evoke an idea and teach a lesson. So, when John Harris published his Peter Piper’s Practical Principles of Plain and Perfect Pronunciation (1813) – which included the well-known ‘Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers’ – his purpose was not to tie tongues but to free people from social bondage through improved speech. He saw clearly that in hidebound Georgian Britain how something was said mattered as much as what was said. As is important is a principle I learned years ago: ‘It’s not what you say, it’s what people hear that matters.’ Communication is, after all, about much more than words.

Alliteration can have a use, though: it helps us remember. Psychologists and advertisers know this. Psychological Science (July 2008) cites three experiments which ‘underscore the interaction between alliteration and memory’. When sounds are similar, the memory engages – and it doesn’t matter if the alliteration is heard or read, or even on the same line. As the experts found, ‘[R]epeating patterns of sound in the form of rhyme and alliteration aid memory more broadly and in less time than either imagery or meaning … [C]oncepts presented early in a poem (or prose passage) were more available (viz. memorable) when alliterative sounds overlapped between lines than when there was no overlap’. If we want what we say to be heard and remembered, the words we use and how we use them matter. But we know this, don’t we? Maybe. But it doesn’t, I would argue today, always appear so.

My title this week isn’t because I like Ms – or even M&Ms! – I am practicing a principle adopted by Coca-Cola, Dunkin Donuts, Best Buy and Blackberry, and (doubtless in honour of John Harris) by ‘Pickled Pepper Deli’ in Hook (Hants, UK) and by ‘Pickled Pepper Books’ for children in Crouch End (London)! Taste and memory engage more powerfully when sounds repeat, evoke and stir our consciousness. It’s not only brand specialists who see this. Here’s master wordsmith William Shakespeare (1564-1616) at the start of Sonnet 30: ‘When to the sessions of sweet silent thought, / I summon up the remembrance of things past.’ Let’s be clear: when books were costly and few, every literary device that helped inscribe words indelibly on a reader’s mind and memory, was priceless. Alliteration was a favoured tool in a poet’s work box. Here’s American poet, author, and literary critic Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) in full alliterative flight in his sonorous poem ‘The Bells’, penned in the year he died – and in which the word ‘bell’ tolls thirty-six times!

(Unknown author; Restored by Yann Forget and Adam Cuerden – Derived from File:Edgar Allan Poe, circa 1849)

Hear the loud alarum bells –

Brazen bells!

What a tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of Night

How they scream out their affright!

If we doubt alliteration’s power, contrast (as other scholars argue) the well-known line ‘[A]ll along the raw and rutted road the reddish barn’ with a non-alliterative counterpart ‘[A]ll along the creek-winding road, past Stuart’s barn’. Like the deadly rattle of a machine gun, alliteration penetrates the thick armour-plating of our dull minds and memories.

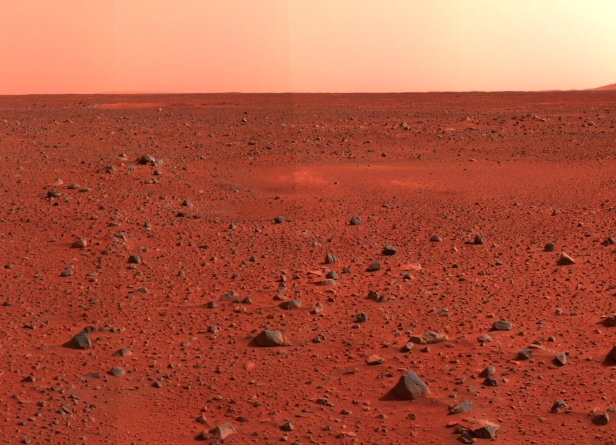

So, are there links between my ‘Ms’ that I want you to see and remember? Are there hooks and tags between them that ‘startle’ and ‘scream’ to use Poe’s words? I certainly hope so. In a week that has seen Harry and Meghan (or the Duke and Duchess of Sussex) once again on TV screens and front pages, beside grim images of soldiers shooting protesters in Myanmar and impressive close-ups of the surface of distant Mars, it’s good and right we allow these ‘Ms’ to bump into one another in our mind, like dodgems at a fairground. After all, that’s what morality does, or certainly aims to do, isn’t it? Just as Harris’s ‘pickled pepper’ sought to train tongues and refine lifestyle, morality sharpens perception and shapes action. In a world confused about possible moral ‘absolutes’, such accidental comparison and self-conscious self-examination offer some light and hope. They set Meghan and Myanmar and Mars side-by-side with rhetorical, moral force. They ask what they say about and to each other. How they relate in our interconnected world and in a necessarily integrated moral universe. They challenge the values we bring to bear – or, tragically, don’t and won’t bother with – when confronted by tragedy and selfishness, by wanton ingratitude and miserly materialism. We may not always enjoy media headlines and coverage; that doesn’t mean we can’t turn them into Poe’s tolling bell to stir slumbering morality and careless myopia. As Poe himself says,

(By Dougsim – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Yet the ear, it fully knows,

By the twanging,

And the clanging,

How the danger ebbs and flows;

Yes, the ear distinctly tells,

In the jangling,

And the wrangling,

How the danger sinks and swells,

By the sinking or the swelling in the anger of the bells.

Moral consciousness and self-awareness awakened by sights and sounds we may not want to hear. Making connections – even through accidental alliteration – can do that.

But we can go further. If colour were only determined by the dusty ‘red planet’ Mars – that is, without reference to the vibrant sights and sounds of Asia or rich diversity of rural Britain – what a dull ‘world’ we would inhabit. Mars helps us appreciate what we have. It points up a drab life, a bland amoral Mars-scape, we might say, where there is no ‘absolute’, acute, or vital sense of what really matters; just dull, relative hues shaped by my ‘world’. It is in the contrast and appeal of ‘otherness’ we recover a sense of ‘uniqueness’. Religious traditions, where moral shades are (often) at their most vivid, have the adaptive power of space travel, lifting perception of self and others to new heights and challenging the adequacy of what we believe to be ‘good’ and ‘true’. They do not allow us to sit comfortably when cross-examined and speak ‘our truth’. ‘Our truth’?! What value is that? It’s like saying, ‘I am content to live on Mars, without reference to another.’ That is a dusty, dry, lifeless place to live. It leaves life disconnected, dangerous, and unexplained, like that pitiful, but ultimately profound, French tongue-twister, ‘Je suis ce que je suis, et si je suis ce que je suis, qu’est-ce que je suis?’ [I am what I am, and if I am what I am, what am I?]. To set ‘M’ beside ‘M’ can, we should remember, help discover, or re-cover, ‘Me’.

Two further connections before I end.

First, I will always associate Mars with another perspective on morality; that is, with the fine, creative labours of senior executives Bruno Roche and Jay Jakob, leading lights in creating and promoting the ‘economics of mutuality’ in and through the Mars Corporation. Resisting prevailing business wisdom, the ‘economics of mutuality’ challenged the Mars family – and then other leaders of corporate life – to let spread-sheets expose obsolescence and thence inevitable mutual destruction. In place of this, the ‘economics of mutuality’ promotes the prudence of an expanded ‘triple bottom line’, in which people, profit and planet co-exist in a healthy, productive synergy. To compete for such a prize doesn’t destroy a company, Roche and Jakob show, it builds them – and renews the planet in the process. So, I wasn’t only drawn to images of a distant planet this week, I was thrilled to see Putting Purpose into Practice: The Economics of Mutuality (OUP, 2021) by Bruno Roche and Professor Colin Mayer, has been published. ‘Good business’, as I found myself saying to a group of MBA students a year ago in Tirana, Albania (and often say on my travels to explain the practical ethics of Oxford House) ‘is good business.’ The ‘economics of mutuality’ teaches that. Business thrives when it serves a world battered by protest and self-interest, war, drought, famine and brutal ambition.

Second, the unfolding tragedy in Myanmar – where it is said more than 100 protesters have now been killed by a brutal, trigger-happy military – raises (again) the issue of moral diplomacy and the ethics of international relations. Diplomatic outrage and Security Council resolutions cut little ice in the face of brutal regimes. Who listens? Who cares? The link between Myanmar and Morality is weak internally and, alas, externally. We allow time and tide to erode the memory of progress made there in the last ten years and overlook the miserly materialism of General Min Aung Tang and other junta leaders. We impose Magnitsky sanctions (for the gravest crimes against humanity) on their travel and banking but do so as much to look good as effect change. Sounding the note of ‘ethical diplomacy’ is no better than Poe’s tolling bell for impending threat, if not accompanied by action that liberates the politically tongue-tied and physically bound. Yes, what we say and how we say it matters. As important are the actions that turn fine expressions into transformative deeds. Sadly, in the clippings on the newspaper editor and politician’s floor we find the Ms – and every other alliterative letter in our alphabets – lying around in a disjointed, disconnected, amoral (and thus immoral) way. That would never satisfy the rigorous formation expected of John Harris’s protégés or of their skillful French cousins. Of course, morality is more than words, but it takes as much practice as a tongue-twister.

Christopher Hancock, Director