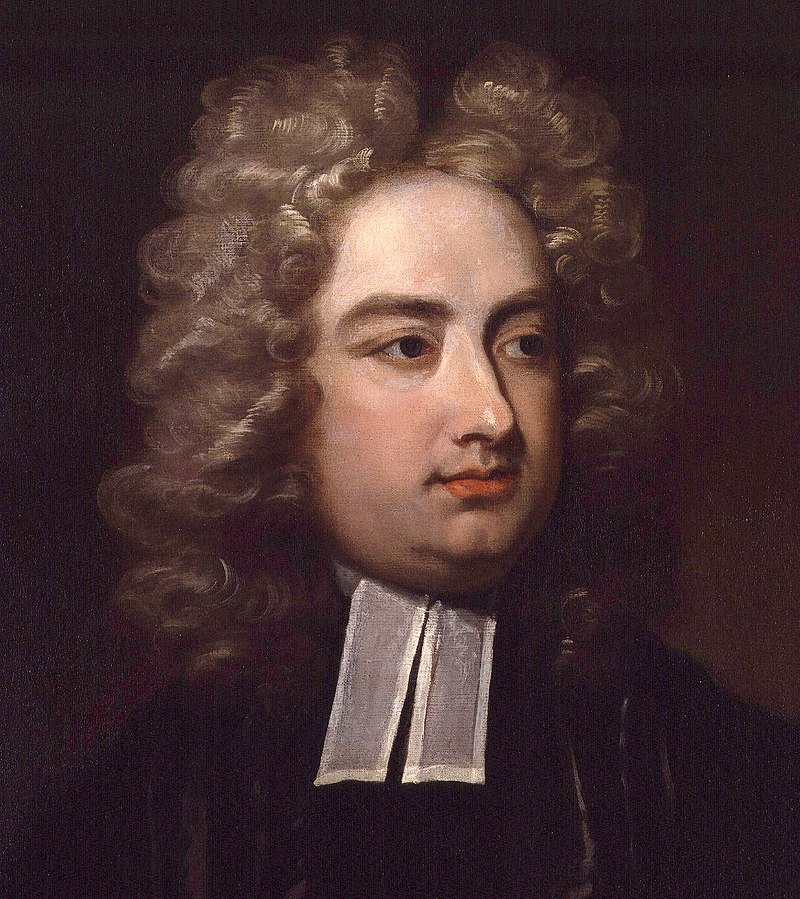

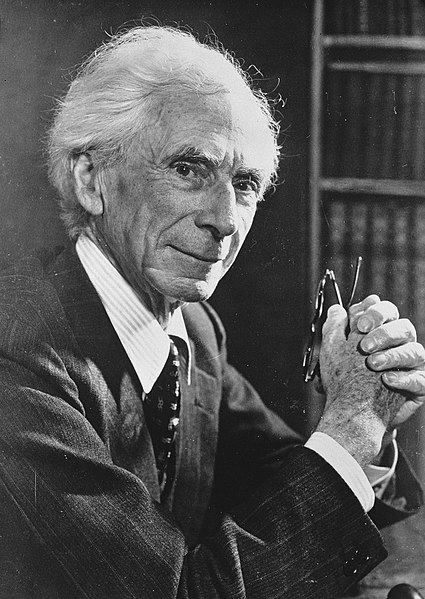

The satirical, politically-engaged essayist, and Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) – known by many for his mythical tale Gulliver’s Travels (1726) – memorably declared on one occasion: ‘We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another.’ His words have always seemed to me dangerously close to the mark! Religion an instrument of hate, a stirrer of crusades, an inciter of violence, a breeding ground for prejudice, a prompter of self-righteousness … to many honest insiders, and rather more irritated outsiders, religions of every kind are guilty as charged. To the angry, atheist German philosopher Frederick Nietzsche (1844-1900) the Christian church was the embodiment of ‘morbid barbarism’, and ‘a form of mortal hostility to all integrity, to all loftiness of soul, to all discipline of spirit, to all open-hearted and benevolent humanity’. Rather than elevating humanity, in its decadent pursuit of power and control it created a weak ‘herd mentality’ and, as he said, ‘a hatred for the “world”, a curse of the affective urges, a fear of beauty and sensuality, and a yearning for extinction’. Unexpectedly, perhaps, Nietzsche does not extend his vitriol to Jesus himself, who is for him the one ‘true’ Christian. The equally famous atheist philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) was similarly harsh, claiming: ‘… as organized in its churches, [Christianity] has been and still is the principal enemy of moral progress in the world’; but he, too, still says of Jesus, ‘He had a very high degree of moral goodness.’ The individual not the institution. And let’s be clear: this merciful sundering of the leader from the led is, to many devotees much of the time, the only thing that keeps them going!

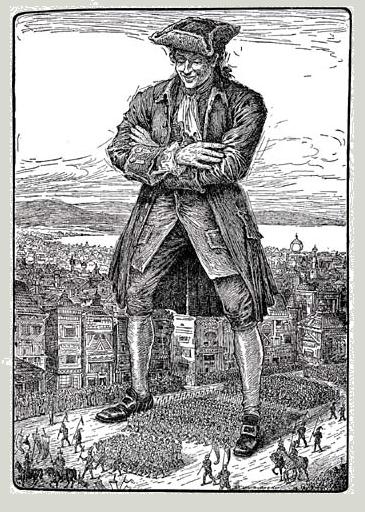

Swift is a fascinating character. As his words and position suggest, he was both an iconoclast and an institutionalist; his position as an Irish Cathedral Dean creating dangerous distance for the English establishment. There is fire in Swift’s belly. His satire is biting. As he said of his aim in Gulliver’s Travels – written at a time the world was shrinking and travelogues were in vogue – ‘to vex the world rather than divert (viz. entertain) it’. Mockery, misogyny and misanthropy are stock-in-trades of his literary style. Petty political and religious disputes are intensified, crimes and their punishment magnified, the meaning of sense and the point of life subjected to searing scrutiny. The famous inversion of scale between the giant Gulliver and the six-inch Lilliputians is a trope for a world without perspective. Old institutions and new science are scathingly represented. In other works, he lambasts British politics and politicians and lauds Confucian China. Far from esteeming the individual as a sensible citizen (as fellow writer, spy and trader, Daniel Defoe [c.1660-1730] had most recently and successfully done in his best-selling Robinson Crusoe [1719]), Swift challenges the confident social paradigm of many contemporaries. ‘We are in more of a mess than you may think’, he seems to be saying. And established religion and moral shibboleths are part of the problem. Travel – he is keen to point out to those who imagine the new colonies across the Atlantic or the recently mapped Far East to be full of Utopian potential – does not solve the problem of a diminished human spirit or a dislocated political estate. We carry our problems with us.

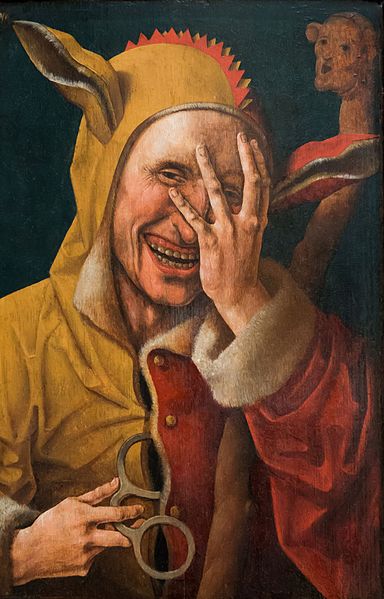

Political and social satire, of the kind Swift and other members of the so-called ‘Scriblers Club’ formulated, was not their invention, of course. The Greek dramatist Aristophanes (c.446-386 BCE) famously indicted the politician Cleon, while Roman authors Martial (c.40-102 CE), Tacitus (56-120 CE), and the ‘Cynic’ philosophers (from which we derive the word), never hesitated putting the literary boot into prevailing ideas and eminent peers. In the name of speaking reasonable truth, satire has as often inflamed situations as pacified them. Few see Swift as an instrument of the Christian love he so zealously proclaimed! But though we may ridicule his endeavour, and smile at political puppets or laugh at the languid lampooning of leaders, the sad and serious fact is satirists today are rarely motivated by Swift’s high ideals and genuine concerns. That kind of elevated, passionate engagement is out of style and out of favour. We cannot even hate, we might say, with Swift’s skill and sound reasoning!

The relationship between religion, language, liberty and hatred is one our world wrestles with, in new ways today. Few religions get off scot free. As the Old Testament Psalmist complained on one occasion, ‘I am a man of peace: but when I speak, they are for war’ (120.7). Religions (and their followers) are, it seems, too often tried and found guilty before their case ever reaches the court. The subtlety and sophistication seen in Swift’s critique of humanity, religion and society are rarely part of contemporary socio-political discourse about religion. In comparison with previous generations, we are rather more like squabbling, petty-minded, little Lilliputians than the gentle, albeit gauche, giant Gulliver.

So, what’s to be done? Let me suggest three things prompted by Jonathan Swift.

First, to encourage and defend free and freeing speech. Alas, much so-called ‘free speech’ today has anything but a liberating agenda: its aim is to muzzle the mouths of those who disagree. Genuinely ‘free speech’, of the kind Swift and his Scriblerian colleagues celebrated, was ready to say the socially unsayable and promote the politically unpopular. If the church never listens to a Nietzsche or Bertrand Russell it risks fulfilling their worst condemnations. Swift was plain right: we do – often – have enough religion to hate and not enough to love!

Second, to promote and protect social humour and playful satire. I was reading a sophisticated study of the English novelist Jane Austen (1775-1817) a few months ago that lamented the degree to which she had been co-opted to ‘serious’ modern agendas. Similar sentiments are expressed in Harold Bloom’s magisterial work Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (1998): ‘the Bard’, Bloom argues,being manipulated to fit one or other of the very latest ideological agendas. Humour and playfulness are, it seems, dangerously lightweight! The fact that we know (by repute at least) Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels is, surely, a good reminder that good points can be made in different ways … humour and satire being two of them. I, for one, have much sympathy with the (presumed intense) Protestant Reformer Martin Luther (1483-1546): ‘If there isn’t laughter in heaven then I don’t want to go there!’

Lastly, and more seriously, Swift is also a reminder that what is said and what is heard are both our responsibility. The carefree offensiveness in Swift’s misogyny and misanthropy is justly condemned. If society (and the Academy) has learned anything in the last fifty years, then it is the power of words. ‘Hate speech’ is a reality. Incitement to violence is a noxious ill. Unnecessarily ‘exclusive’ terminology and demeaning humour are plain wrong. But so, too, is the projection onto religion of agendas and actions they repudiate. Sometimes, like the Psalmist, they are truly ‘instruments of peace’ (as St Francis prayed that he would be) but are presented as always guilty of warmongering. If you ever doubt that, cast your mind back to individuals behind institutions, to a Confucius, Buddha, Jesus, Abraham and Mohammed.

Christopher Hancock, Director