The twists and turns of this year’s US Presidential Election are keeping commentators and electors unusually busy. Industries and individuals whose livelihoods depend on making and selling ‘news’ are delighted, of course. We don’t need them to tell us more is to come! Our world is full, overfull surely, of what is still (presumptuously or naïvely) called ‘news’. It is, alas, rarely worthy of that old, respected term, being more often now a foul-smelling potpourri of unwashed human habits or artificial concoction of new, media-driven values. Attempts to make ‘fake news’ a news story should make us all despair of what was, once upon a time, an elevated literary form of art and science, creativity and (reliable) data. With so much ‘news’ infected by politics, agenda, and personality, it is no surprise if a new virus of news-weariness spreads. More media platforms may after all mean less public interest!

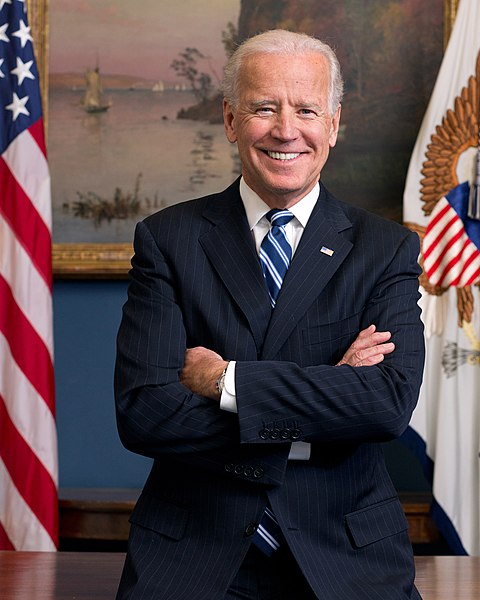

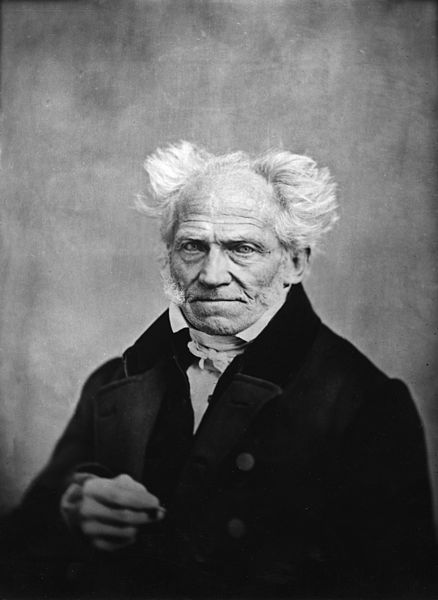

Just occasionally something interesting crawls out of the ‘news’ room swamp. I suggest this happened last Tuesday night. During the first, acrimonious, televised debate, something newsworthy occurred. The Democrat presidential candidate Joe Biden replied angrily to a barracking President Trump, ‘Shut up, man’. To my mind this is newsworthy. Not, I should hasten to add, for its political significance but for the light it sheds on silence; that rich, but oft forgotten response we see in the face of mystery, grief and ‘the holy’. Others have picked up on Biden’s words. Jonathan Capehart wrote this in a Washington Post article entitled ‘Joe Biden spoke for millions when he told Trump to “shut up, man”’ (1 October 2020): ‘President Trump’s performance at the first presidential debate was so petulant and disgusting that it has taken me this long to put my thoughts to pixels … What was breath-taking on Tuesday was the ferocity of his bullying.’ Capehart is clearly not first in line to re-elect the President! But his words do more: they add to the ‘news cloud’ that overshadows our life. Silence lets the dust settle, the sun break through, the ghastly fall away, for, what German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) called, ‘that coy beauty truth’ to make an appearance.

Glasshouse-dwellers in modern Western democracies risk much if they throw rocks at one another. With the debacle of Britain’s exit from the EU once again front-page ‘news’, no fair UK citizen can criticise trans-Atlantic politicking. Silence, at such times, makes reasonable sense and makes sense reasonable. Passion, like ignorance, is unlikely to see things clearly. Once again, the wisdom of the Old Testament Book of Proverbs comes to mind: ‘Even a fool is thought wise if he keeps silent, and discerning if he holds his tongue’ (17.28). Silence as a sign of wisdom. What a staggeringly counter-cultural claim! Modern ‘news’ believes, ‘Talk and talk and people will believe you.’ The wisdom of silence says, like Biden, ‘Shut up, man’.

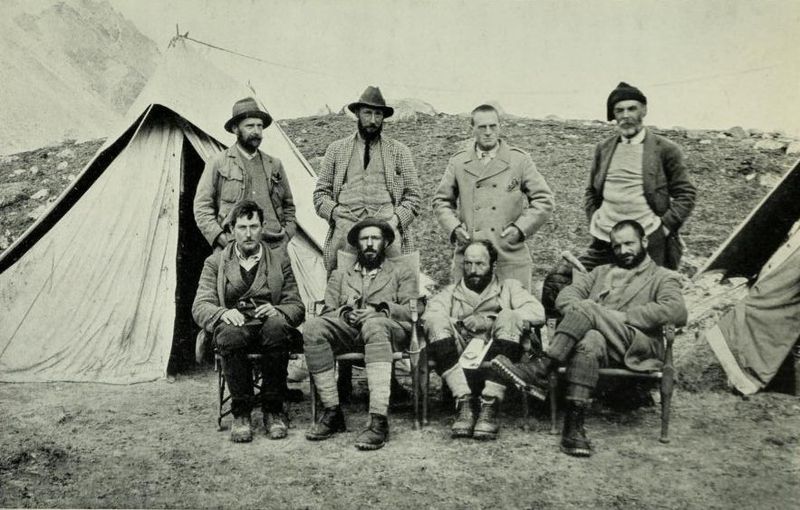

Silence is sometimes the best and only place we can go. I have just finished US author Wade Davis’s excellent book Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest (Vintage 2012), which my son-in-law gave me for Christmas last year. Having taught at a Cambridge College with a Mallory Court and a Benson Hall, I should have known more than I did about the earliest attempts (1921, 1922, 1924) to climb Mount Everest, or, as Tibetans call her, Chomolungma (or a variant). The Tibetan name has a host of possible meanings; including, as the Royal Geographical Society proposed at the time, ‘Mother Goddess of the Country’ or ‘Goddess Mother of the World’. To the young – and not so young – teams of climbers drawn into the earliest expeditions, the highest peak in the world held inherent attractions: attractions, no amount of cold, wind, danger, sickness, politics, death, poverty, discord, or poor news reporting could dispel. The story is well-worth taking time to digest.

The power of Wade’s careful narrative lies not in its detailed account of the pains taken to plan, promote and execute the first three (unsuccessful) ascents, but in the deeper reasons for them and the larger lessons from them. Silence is in the title and the heart of the story.

There is silence in the way members of the first Everest expeditions, who had served and suffered as soldiers and medics in the stench of the trenches of Ypres, Passchendaele and the Western Front, handled the post traumatic stress of daily bombardments and mutilated bodies. Like so many who have known active service, those who first sought to conquer the world’s highest peak, knew the pain and silent suffering of war – and made little sense of it except in companionable silence with fellow sufferers. Everest was a path to personal and national redemption, scaling it a way to heal the dashed hopes of a generation and empire.

There is silence, too, for Davis in star-spangled nights and excruciating climbs when the magnitude of the endeavour, etched into the sheet ice and menacing rock of the North Coll and Rongbuk Glacier, made speech impossible or palpably meaningless. But the mountain spoke. Like the mythic sirens of Jason’s journey in the Argonaut, it called out to be ravished but killed those who approached. The first three attempts on Everest saw twelve men die.

There is silence, too, spiritual silence, that follows the Buddhist blessing and prayers of the 13th Dalai Lama in Lhasa and monks at the fortress monasteries of Rongbuk, Shegar Dzong and Kampa Dzong. Their silence also speaks, even to those members of the team who had lost God in the blood of the Somme. It is a deliberate silence: the silence of Buddhist faith and popular veneration for ‘Goddess Mother of the World’ and the deities and demons of its soaring slopes. ‘Shut up, man’, we can almost Everest saying now as then.

Silence speaks. To Jewish and Christian mystics, it lies between speech and a beatific vision of the Almighty. The magnitude, agony and deafening noise of a ‘news’ ridden world make silence an important option. To presume to speak when so much is unintelligible or futile only adds to the noise. To pronounce confidently on the possibility of humanity scaling the ‘Everests’ of humanity’s early 21st century problems looks as foolhardy as British imperial assumption supplementary air wasn’t needed by gentlemen on the mountain. Silence may be a better option than shouting. And to deny any space for spiritual silence may be as hard and blind as those of Mallory’s team, who had no Bible in their backpack or heart to respect their Tibetan Buddhist hosts: hosts, let’s be clear, who wouldn’t say, like Joe Biden, ‘Shut up, man’, but whose silence may have meant the same. Silence speaks … if we give it a chance.

Come back to Schopenhauer. He has many faults. His passion for truth should still impress. Here’s the full quotation referenced earlier: ‘Truth is no harlot who throws her arms round the neck of him who does not desire her; on the contrary, she is so coy a beauty that even the man who sacrifices everything to her can still not be certain of her favors’ (The World as Will and Representation, 1888, I. xix).We can learn from Schopenhauer’s pessimistic view of his day and age, that inspired him to look East to Buddhism and Confucianism for ideas and ideals. We can almost hear a ‘Shut up, man’, and condemnation of our modern ‘news’ media, later in the Introduction to his famous monograph:

My guiding star in all seriousness has been truth. Following it, I could first aspire only to my own approval, entirely averted from an age that has sunk low as regards all higher intellectual efforts, and from a national literature demoralised but for the exceptions, a literature in which the art of combining lofty words with low sentiments has reached its zenith.

We may have an Everest to climb to reverse the process of global, cultural decay today: that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t attempt to scale it. But I should give the final word to one of the brave men who beat a sad retreat after George Mallory and his climbing companion Sandy Irvine’s unexplained deaths (c. 6 June 1924). The team is back again at Rongbuk Monastery and join a prayer service halfway through:

Hitherto we have felt nothing but repulsion for the lamas: their mode of life and everything that pertained to them. We were therefore hardly in a mood to be prepossessed. Yet it must be admitted that that was one of the most impressive, the most moving services I, for one, have ever attended. Perhaps it was the unexpectedness of the whole thing, and especially of the worshippers’ profound devotion. In any case it must have been only an appeal to eye and ear, and not to the conscious mind, for we could not understand one word of what was said (553).

Silence. Not pious quietism or grumbling withdrawal. but firm, active, humble, awe-filled silence in the face of big things that matter and small things that don’t.

Christopher Hancock, Director