Some people are making money out of COVID-19: many are not. Depending on their field, some researchers have never known it so good: others are out of a job. Investment in finding an effective vaccine against coronavirus is a plausible priority. Pharmaceutical companies, like on-line marketing and food suppliers, producers of PPE, cleaning products and hand sanitizers, are booming. Many are not. The Western world faces a grim autumn and winter of discontent as the full economic impact of the pandemic begins to bite and unemployment soars. Meanwhile China rises, India struggles, Brazil bleeds, Beirut rebuilds and countless millions of the unnamed suffer in silence, forgotten. Though autumn’s changing colours and falling leaves are not a global reality, the ‘mists and mellow fruitfulness’ of British Romantic poet John Keats’s (1795-1821) ‘To Autumn’, hang heavy on us all. Like the bereaved, many hope to wake and find the loss of normality just a dreadful dream. After the initial numbness, anger, accusation, and depression are common features of the second phase of bereavement. The world is entering that phase with COVID-19. It may not be pretty. True loss rarely is.

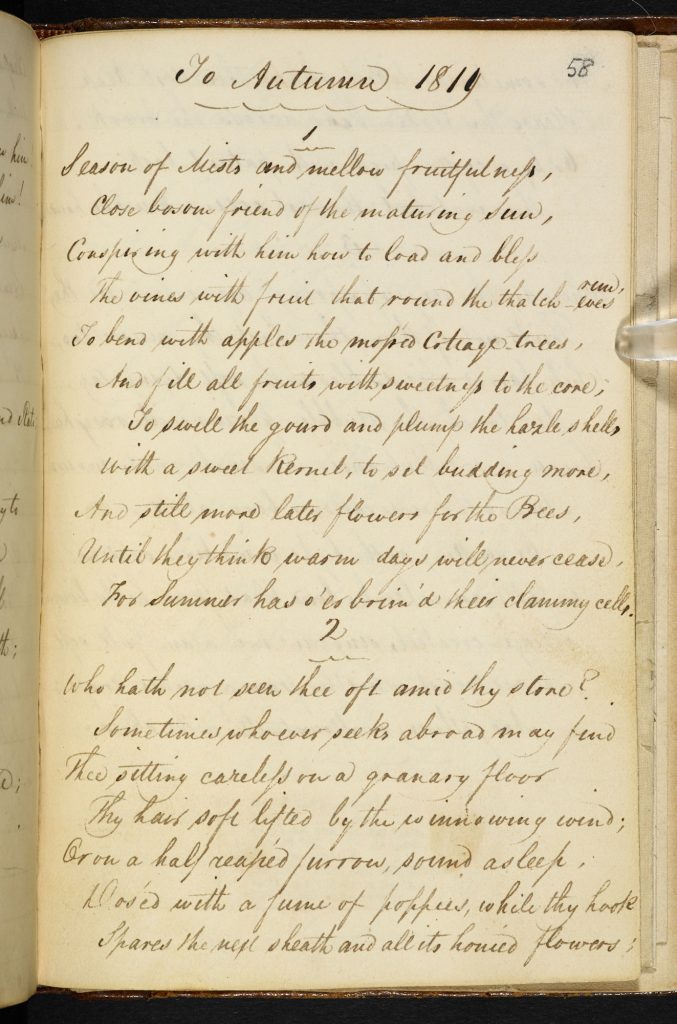

Keats’s ‘Ode to Autumn’, is always an interesting conversation partner, especially now. Here’s stanza one again, for your enjoyment:

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

Written in September 1819, ‘To Autumn’ is the last of the set of ‘Odes’ Keats wrote that year (which include the equally famous ‘Ode on a Grecian urn’ and ‘Ode to a Nightingale’). He was desperate to make a career and a living as a poet. ‘To Autumn’ signals the end of his attempt. He died a little over a year later. Like many past and present, financial troubles dominated Keats’s life – even as he wrote ‘To Autumn’. You wouldn’t know it – certainly not from the poem’s opening lines. It is surprisingly full of hope – and a good antidote to autumnal glums.

Here is the second stanza for you to savour, like a ripe peach.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

Given its autumnal theme, many assume the poem is about mortality or failure, hopes dashed by the perennial problems of human existence: promising so much but (always) ending in bitter disappointment. Acute historical commentators also point to the political troubles that befell Britain in 1819; to say nothing of the profound socio-economic effects of the Napoleonic Wars that had ended but four years earlier. The ‘Peterloo Massacre’ on Monday, August 16th – when a troop of cavalry in Manchester charged a crowd of 60,000, who were demanding political reform – is still one of democratic Britain’s darkest days. And then there was Keats’s beloved brother George’s struggle to settle in America. Mists hung heavy over Keats. He might feel justifiably depressed. But this isn’t the heart of his art. His poem flows through the phases of autumn, from ripening to harvesting, yes, but he is aware the ‘cyder-press’ follows! In fact, his diaries suggest it was a delightful walk by the Itchen river in Winchester that stirred his autumn reflections: not death or morbidity, but seasonal beauty fill his soul. Romanticism treasured the wonder of nature too many forget.

Here’s the third and last stanza of what some see as the archetypal short English poem:

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

Notice those first two lines: ‘Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?/ Think not of them, thou hast thy music too’. Autumn, he is saying, ‘thou hast thy music too’. Yes, Spring is great, but you have your own beauty, truth, and seeds of hope. Though the ‘swallows twitter in the skies’ (as they do on the barns I look down on from my study), preparing to fly south, they will in the course of natural time return. Such are seasons. As ancient wisdom declares: ‘To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven …’ (Ecclesiastes 3.1).

Two things strike me as I read Keats’s words, ponder our world, and prepare to return to work at the end of summer. First, the extraordinary maturity of his perspective. Pain has a way of doing that: it makes us dig deeper, mature beyond our years. Keats was only twenty-four when he wrote his ‘Ode to Autumn’. He was in the Springtime of his life – and yet he could already see other seasons in life had their own, unique riches. That is impressive. Our mad, materialist, hedonist world is fixated on sexy Spring hopes – always asking, it seems, ‘Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?’ – or slick summery sensations. Perhaps COVID-19 will make us think more deeply; not in a sad, morbid, fatalist way, but with Keats’s surprisingly mature confidence that riches are found in non-materialist ways … to those with eyes to see. Here’s Keats, writing on 21 September 2020, as he reflected on what had moved him to compose his newest poem: ‘How beautiful the season is now – How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it […] I never lik’d stubble fields so much as now […] Somehow a stubble plain looks warm – in the same way that some pictures look warm – this struck me so much in my sunday’s walk that I composed upon it’ (Life and Letters [2008], 184). Keats had many reasons not to see life, his life, like that. Well done, him that he did! Shame on us when we don’t.

The second thing Keats’s ode prompts me to recognize is, to parody the poet, the state of ‘mellow faithfulness’ seen in many people of all faiths and none who eschew superficiality, perhaps suffer long, certainly think more deeply about life, and so bear the riper fruits of seasoned characters, calmer consciences and contented souls. Theirs, too, is a ‘cyder-press’! My hope for Oxford House, and writers of other ‘Weekly Briefings’ this autumn, is that as the days of COVID-19 draw in and darkness descends, hope will shine through in all we do.

Christopher Hancock, Director