Ten-years ago last December, the 26-year-old market-stall holder Mohamed Bouazizi set himself alight in Sidi Bouzid, a town in central Tunisia. It was an act of utter desperation and bitter frustration at the corruption which had wracked his country for more than half a century. Like a match to dry kindling, Bouazizi’s self-immolation triggered bushfires of protest which swept through Tunisia and subsequently the whole Middle East and North African region (MENA). Ten years on, it is appropriate we reflect on what, if anything, this so called ‘Arab Spring’ (Arabic: الربيع العربي) achieved, and what kind of future the countries it touched face.

The excitement around what some saw as a longing for Western democracy was palpable. Editorials and online media hailed a ‘new dawn’ for the region. To Islam Hassan and Paul Dyer in 2017, the world watched the ‘Arab Spring’, ‘gripped by the narrative of a young generation peacefully rising up against oppressive authoritarianism to secure a more democratic political system and a brighter economic future’ (‘The State of Middle Eastern Youth’, in The Muslim World 107.1: 3-12). The very name ‘Arab Spring’ evoked for some the ‘Springtime of Nations’ in the pan-European 1848 revolutions, for others the 1968 ‘Prague Spring’ when, much like Bouazizi, Czech student Jan Palach set himself ablaze to protest Soviet domination. Some local reporting traced the new movement’s name to US commentary and saw American aims and ambitions writ large in it. Excitement was not universal. Unease gripped European capitals (and America) at the local and regional instability revolutionary protest might bring. Officials with long memories recalled street-fighting in Beirut and the criminals, terrorists and opportunists who thrived in the chaos of the Lebanese civil war (1975-92). And, as world leaders knew, authoritarian regimes in MENA had survived with the backing of Western governments keen to protect their oil supplies and prevent hostile insurgents. Widespread protest meant the future was as predictable as the toss of a coin.

(U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Awalt)

Concerned about the spread of instability, and arguably even more anxious not to get drawn in, a mixture of humanitarian sentiment and economic self-interest did produce one notable Western intervention … in Libya. With the mandate of UN Security Council Resolution 1973 (February 2011), Britain and France engaged in an air war between March and October 2011 in support of rebel forces who sought to topple the brutal and volatile dictator Colonel Mummar al Gaddafi (1942-2011). For almost 35 years, Gaddafi had terrorised fellow citizens and wreaked havoc in the region and beyond, first as Revolutionary Chairman of the Libyan Arab Republic (1969-77) and then as the ‘Brotherly Leader’ of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977-2011). Allied forces prevailed. On 22 October 2011, with his forces and regime in tatters Gaddafi was assassinated. Since then, those fearful of the consequences of popular protest in MENA have been vindicated many times over. Since 2011, Libya has been plunged into an ever deeper and darker vortex of chaos, its revolution painfully partial, its friends palpably disloyal. As the Libyan academic and journalist Dr. Mustafa Fetouri wrote in 2019 ‘… the situation on the ground has passed the point of no return. Any peace deal now is far more difficult to envisage. The actual decision of war and peace now rests in the hands of the militias and their foreign supporters’ (‘Why is Libya so chaotic and ungovernable?’ Middle East Monitor, 2020). ‘Arab Winter’ would be a better name for this.

If Libya exemplifies the worst result of the ‘Arab Spring’ ten years on, it is vital we see that the factors which created this tragedy were not unique to Libya. This is important: it means we should not demonize Libya nor castigate Britain and France for their well-meaning intervention. It also forces us to ask ten years on: What factors and forces led to the ‘Arab Spring’? And, why did protests in MENA in 2010-11 not lead to the stable, representative governments many inside and outside the region hoped for? Three crucial points need to be made in answer to these questions.

(By User:ليبي_صح – User:ليبي_صح, CC0)

First, the disconnect between the ruling political elites and the rest of the population was such that, even when Gaddafi was removed in October 2011, there was no one outside of the previous ruling cadre with any real experience of leadership or government. In other words, the power vacuum that the toppling of Gaddafi created – and the problems that followed as a result – was not unique. Throughout MENA, when leaders and regimes fell there were few people and systems in place to replace them.

Second, the speed with which protest led to change in the ‘Arab Spring’ caught everyone off guard. There was no time for socio-political and economic preparation. Even when, as in Egypt, an established body could form a government (viz. the Muslim Brotherhood), the speed of change and pressures of decision making, proved too great. It was not long before the government of Mohamed Morsi (1951-2019; Pres. June 2012 to July 2013) and the Egyptian Brotherhood’s inadequacies – not least their hastily constructed economic proposals – prompted the military under General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi (b. 1954), Commander-in-Chief of the Military and the Defence Chief, to seize power (July 2013). As it was, this military intervention was not implausible. Al-Sisi had been a member of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), set up after President Hosni Mubarak’s (1928-2020; Pres. 1981-2011) ousting (11 February 2011) to ensure a peaceful transfer of power. The Egyptian army’s brief had for decades gone beyond security. It had been involved in major infrastructure projects since the 1970s (e.g. land reclamation, civic development and rebuilding the Suez Canal). Prior to Mubarak’s fall its direct economic control was, however, limited: that soon changed. To Malcolm Kerr (Carnegie Middle East Center), the Egyptian military now controls ca. 25% of all government spending on housing and infrastructure. There is political stability here, yes, but is it representative?

Third, external actors intervened in the internal affairs of weak and unstable countries. This phenomenon is all too common. Opportunistic regional and global powers neighbours smell blood and pounce. New agendas mingle with old rivalries and the historic status quo. As we have seen, the Libyan situation was not improved by international intervention (albeit with UN endorsement). Since the formation in 2015 of the Government of National Accord (GNA), which controls Tripoli and the West of the country, Turkey, Italy, and Qatar have all it offered support. Opposing the GNA is a confederation of militias (the ‘Libya National Army’, LNA) under Khalifa Haftar, who assisted Gaddafi take power in 1969. The LNA is funded by Egypt, France and the United Arab Emirates. The prize for the winner is Libyan oil but economics are not the sole reason why outside intervention takes place. Elsewhere in the Arab Spring states, internal problems have been susceptible to external influence, often to advance larger geo-strategic agendas. In Syria, for example, as Alexander Pearson and Lewis Saunders argue in a January 2019 article, America, Russia, Iran and Turkey have all had strategic reasons for funding the different sides in the civil war (see www.dw.com).

These three factors have ensured that the fires lit by the events of 2010-2012 have either been smothered by new forms of authoritarianism or spread to new types of political and religious extremism (note, as I write, ISIS is astir again and suicide bombings in Iraq have returned – a future brief will engage with this). To all of this, notwithstanding the slaughter of holidaymakers in June 2015, Tunisia, where Bouazizi’s self-immolation ignited the hopes and dreams of many young Arabs, is a notable exception. Though Human Rights issues remain, Tunisia has witnessed an unexpectedly successful transition to representative government. Indeed, if you are looking for a ‘success’ story (albeit with caveats) from ‘Arab Spring 1.0’, Tunisia is it.

Looking ahead there is probably more cause for concern than optimism in MENA. The legacy of the ‘Arab Spring’ lives on, but more as a warning than an inspiration. Indeed, there is good reason to believe MENA may erupt again … and soon.

What indices suggest all is not well in MENA?

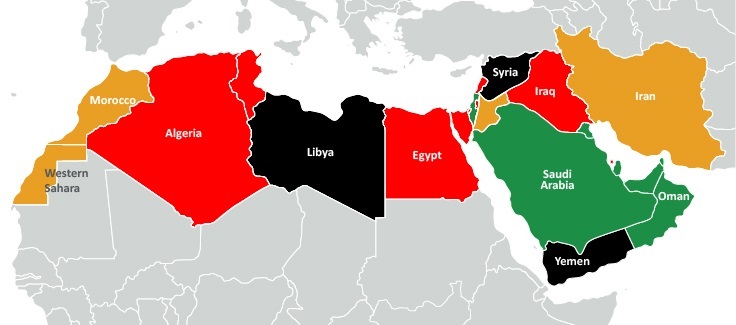

extreme (black), high (red), medium (yellow) and low (green).

(The red24 report 2017, my.worldaware.com)

Take Lebanon. The explosion that rocked Beirut on 5 August 2020, destroyed much of the port and commercial district, as well as four of the city’s main hospitals and countless clinics. The accident fanned flames of socio-political dissent that had been raging for some time. The coronavirus pandemic has made matters worse. Citizens have been struggling for years with civic corruption, government incompetence, failing services and rising unemployment. That the government defaulted on a $1.2bn Eurobond loan in March 2020 came as no surprise. Is Lebanon ripe for revolt? Absolutely.

(mehdi shojaeian https://www.mehrnews.com/)

Add to this the fact that youth unemployment and economic decay are commonplace in MENA, and ‘Arab Spring 2.0’ begins to look more and not less likely. In 2016 youth unemployment stood at 30% across MENA (cf. global average 13%). As if this is not challenging enough, the region has the youngest average age globally (22 yrs.) and, thus, the highest number of young people as a percentage of its population (60% under 25). In part, the ‘Arab Spring’ was a response to this demographic reality. The problem remains; despite the attempt of oil rich countries like Saudi Arabia to export the problem through student scholarships overseas … until, that is, the price of oil crashed five years ago. The fact remains, MENA and Gulf Cooperation Countries (GCC) have failed to create enough jobs to reduce youth unemployment long term.

Corruption – in protesting which Mohamed Bouazizi gave his life – also remains a major issue in MENA. With definition and perception of ‘corruption’ part of the problem, precise figures are hard to confirm. Transparency.org provides some useful data. Their 2019 report ‘Global Corruption Barometer: Middle East and North Africa’ shows 65% of MENA citizens believe corruption rose between 2010 and 2019 and government officials and parliamentarians are the worst culprits (www. transparency.org).

Statistics make for serious reading in the MENA region. When tied to frustrations with the handling of the COVID crisis, a ‘trigger moment’ threatens.

A deeper, persistent problem is that too few have been willing to learn the lessons of the first ‘Arab Spring’. Throughout MENA there remains a fundamental disconnect between rulers and ruled, elites and the population at large. Take the recent ‘Abraham Accords’ (signed on 13 August 2020). Agreements to normalise relations with Israel – first signed by the UAE and then by Morocco, Sudan, and Bahrain – were welcomed around the world. Previous tacit agreements had already been made by Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Legitimate geo-strategic and economic reasons (esp. relating to Iranian influence, reduced oil prices and pressure to diversify) guided these agreements. However, for people on the street, they underlined the self-interest, short sightedness, and fundamental illegitimacy of government/s. The WION (World is One News) web portal reported on 18 September 2020, that protesters in Morocco denounced ‘treacherous countries’ and their ‘American and Zionist allies’. Such protests could have been heard almost anywhere in MENA.

Ten years on, if ‘Arab Spring 2.0’ is to occur – as an instrument of positive, lasting change – what needs to be different? Little can be done short-term to create a new skilled, more representative governing class. But the international community can choose to meddle less and support more; however, tempting it is to influence decisions or believe ‘the West knows better than the rest’. What is more, if key actors in new political movements prove worthy of trust and grassroots support, long term institutional re-building is imaginable, and the peace and integrity Mohamed Bouazizi died for more attainable. The peaceful transfer of power is not an impossible ideal: it has been done many times before when the contingencies of responsible leadership and a willing people have coinhered.

Sean Oliver-Dee, Associate