It causes me no embarrassment to admit, I love sport! – I always have, and hope to God, I always will. At school, university, and throughout my 20+ years with IMG (the US-based sports, events, and talent management company) sport was central. Sport has helped shape who I am, what I do, and, increasingly, how I see the world. Over the years, it has been my privilege to spend time with some of the world’s leading sports stars and attend major sporting events, and, most recently, to work on projects that are less about sport as an end in itself and more about sport as a means to a better end for individuals, communities, cities, and, ultimately, the planet we all share. Whilst I am also passionate about culture and music, sport has taught me much about myself: I now see it has more to teach me about life itself.

I want to write positively about sport, but everyone who plays or watches a sport knows it has its own ‘highs’ and ‘lows’, its World Cup victories and Olympic Golds, its records and great results. It also has its fatal crashes, broken bones, crushing defeats, and bitter disappointments. If it takes 100s of casts to catch a salmon, it takes 10,000s of hours to make a swimmer like Adam Peaty, a rower like Sir Steve Redgrave, or an athlete like Michael Johnson. No, sport never gives her gold away for free.

For some, sport will always be out of reach: they don’t have the body, the coordination, or a way to access facilities. The Paralympic movement has done much in recent years to show sport’s triumphant face and therapeutic power, but the bar is still too high for many. And there’s elite sport’s grim association with corruption and drugs, racism and egotism, hedonism, abuse and the cult of A-list celebrities, all of which trouble many people, and probably should concern us all more than they do.

Yes, sport has its darker sides: in that it mirrors life. But, as in life, sport’s darkest times sometimes unlock its greatest light: the underdog wins, racism is faced by the Premier League, sexual abuse by coaches is named and condemned, broken parts prompt new designs, unexpected failures lead to re-evaluation and re-orientation of a life. As one of the world’s great thinkers, Saint Augustine (354-430 BCE) said, ‘The black in the picture shows up the gold.’ Sport may not have moral power, but it sure knows how to teach us lessons and inculcate values.

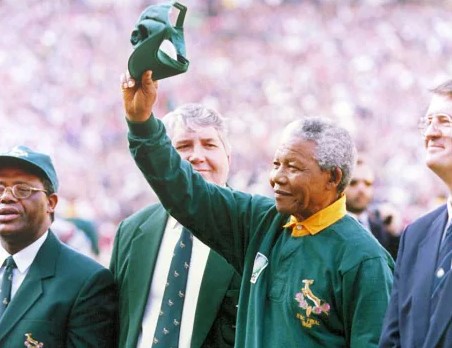

Sport matters in the modern world. One of the greatest sporting events for me was the 1995 Rugby World Cup in South Africa. Apartheid has been in my mind since the death of Archbishop Desmond Tutu (1931-2021). The stand taken on inter-racial sport by that other South African Nobel Prize-winning Human Rights campaigner and politician, Nelson Mandela (1918-2013; President of S. Africa 1994-1999), should never be forgotten. At a turbulent time in his nation’s life, Mandela saw the power of sport to unite, challenge and rebuild society. Here’s part of a speech worth pinning on your locker door:

Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire, it has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope, where once there was only despair. It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers. It laughs in the face of all types of discrimination.

I love the sense of joyful hope here. Mandela saw and celebrated sport’s wilful disregard for a person’s ethnicity and its exhortation to all to excel and exceed expectations. Yes, sport can be cruel, it can also be kind and the cause of unbridled joy. Those who take it too seriously, who shout abuse from terraces or shoot drugs to win, miss the point and impact negatively their own and other peoples’ lives. As Mandela in his Springbok jersey reminded the world in 1995, we find a future on a stretch of grass and identity in a simple sports hall. If lives are lost in sport, they can also be found.

My sports and events consultancy has shown me three things about sport I hadn’t seen as clearly before. Let me talk you through them. I am not expecting you’ll be inspired to sign up for a gym tomorrow after reading them, but I hope they’ll make you ask new questions of yourself, of your local government and the way it plans communal space, and of the international community as it struggles to find safe places to meet in peace and enjoy life together. If sport (of any kind) can go some way to achieving any of this, then it will have done what I – like many sport lovers – believe it can and should do.

First, I am more aware than before of the impact sport can have on individuals. After all, it’s individuals who are jeered at from terraces or mauled by sports commentators. It’s individuals – even in team sports – who feel aching limbs and crunching tackles, who run in the dark and cut down on carbs. Unlike much of our ‘me’ culture today, though, the individualism sport stirs is essentially selfless. I may want to win The Open and claim the claret jug (vain hope that is!), but I know the path to victory is via endless skirmishes with ‘self’. Technique is refined and the lazy player will always be a poor, and usually short-lived, under-achiever, mirroring life.

There’s another side to sport’s impact on individuals: it is has to do with the risks elite sportspeople take when they subject their life (and that of family and friends) to split-second decisions, to the result of singular events, to the few minutes of lung-bursting agony on the way to winning. Take my friend Sir Steve Redgrave, whose 5 Olympic Golds were won rowing 2000m in less than 6 minutes. Behind him, of course, lay 20+ years of blood, sweat and tears, but in the end only the final 6 minutes ever mattered. It is a type of heroism with a different kind of medal. And, lest we proud Brits forget, Redgrave’s was the only British Gold Medal at the 1996 Atlanta Games. Much has changed positively to inspire others to follow.

And then there’s the impact of one person on a sport and a country. The tennis super-star Björn Borg (b. 1956), who in his short career (1974-1981) won the French Open title 6 times and Wimbledon on 5 successive occasions, transformed Swedish tennis. Scottish cyclist Sir Chris Hoy (b. 1976), who won six Olympic Golds (2000, 2004, 2008 and 2012), raised the profile of his sport in Britain and around the world. Dame Flora Duffy (b. 1987), who won Gold in the Women’s Triathlon in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, gave the tiny island of Bermuda its first Olympic medal and a new reason to be proud. And what of the awesome 101 miles run in 24 hours by the Rugby League star Kevin Sinfield (b. 1980) on behalf of his friend and former team member Rob Burrow (b. 1982), who has Motor Neurone Disease. Sporting individuals can raise the bar on sporting achievement: they can also raise the bar on human care and compassion. As Mandela saw in sport, and demonstrated by his life, individuals can make a difference.

One last point on the impact of sport on and through individuals. Sport offers significant health benefits for those who exercise safely and regularly and sets a healthy standard for their nearest and dearest. Healthy fathers breed healthy sons. Active mothers teach their children about a balanced life. Obesity and Type-2 diabetes plague the West. More could and should be done to encourage a healthy lifestyle. Britain lags behind in this. Only 60% of the country take 150+ minutes exercise aweek. 63% are overweight or medically obese. Medical experts say 5.5m. Britons will have Type-2 diabetes by 2030. According to a Sport England ‘Active Lives’ survey, mid-March and mid-May 2020 saw ‘unprecedented’ falls in activity during the lockdown, with 14m. people taking less than 30 minutes exercise per week (up from 3.4m. a year earlier). If COVID continues in some form for years, the need for clear, joined-up thinking by government at a national and local level is clear. According to Sport England, exercise makes good economic sense: every £1 spent on sport and physical activity generates ca. £4 for the economy. Sport is a force for good: it is also a wise investment when it prompts people of every age group and background to live more healthy, proactive, self-disciplined lives.

Second, I am more aware than ever before of the impact of sport on communities. What is true of an individual is true of a successful team. So, cups and medals are paraded before cheering crowds, memberships of sports clubs soar. Children imagine themselves an England opener or American gymnast. Community identities are played out on cricket pitches and soccer grounds. An estimated 75-100m. watch the 120-year-old ‘El Clasico’ game (Barcelona v. Real Madrid). More than 275m. watched India play Pakistan in the ‘mother of all matches’ during the 2019 Cricket World Cup. Local football rivalries in Glasgow, Manchester and Liverpool split cities and families. The Ashes cricket series between Australia and England (which England lost ignominiously in the last few days!) is for many more than a series of games: at stake are national pride and intolerable shame. Wales groans when its rugby team loses. Yorkshire rejoiced when the Brownlees won multiple triathlon Olympic medals in the first two decades of the 21st century. And note, sport-loving Yorkshire would by itself have been 17th on the Rio Olympic medal board!

Sport impacts communities for good and for ill. Recent allegations of racism at Yorkshire Cricket Club have hit the region (and the game) hard. Rioting fans at overseas football internationals leave physical and relational scars on their hosts. A neglected local sports facility is a scandal and an eyesore. As I get older, it is this negative physical impact of sport that stirs me most. The stadium in Atlanta where American sprinter, and former world record holder, Michael Johnson (b. 1967) won two Gold Medals (200m + 400m) in 1984, has been flattened. Like the laurel wreath to winners at Games in antiquity, some of the facilities built to house the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics have crumbled. Cathedrals to sport, which should last like their ecclesiastical counterparts for centuries, are too often the butt of local jokes or lingering legacy of poor workmanship and government hubris.

(Pilar Olivares/Reuters)

In the work I do, I have become more and more sensitive to, and passionate about, the relationship between space and place, between design and impact, between buildings and communities. And I am, thankfully, not alone in this within the sporting fraternity. Sport, and the buildings created to house it, can and should have a positive, engaging and lasting, impact on the communities they serve. Legacy is a critical issue in planning and building for a major sporting event or facility. Function and form are both important, as are the benefits accruing to a community 365 days a year. Too often, planners and developers look to serve the needs of club, team, and fans more than the local community. New facilities in London, on which billions of pounds have been spent – such as the Olympic Stadium (West Ham), the Wembley Arena, the tennis complex at Wimbledon, the new, or re-vamped football and rugby grounds at Twickenham and for Arsenal, Tottenham and Brentford– are all very fine, but do they maximize return on investment for the entire community? I think, sadly, not.

‘Place creation’ is, or should be, as much about inspiration as function, cultivating maximum use and safeguarding it against abuse going forward. Having a gift shop, dining room, corporate entertaining space, or café, and then bolting on a spa or hotel, isn’t enough. Communities want and deserve more from the sporting giants on their doorstep. But around the world a new philosophy for stadia is emerging. After Juventus’s new stadium, plans are now afoot for the San Siro, Milan and The Camp Nou, Barcelona. In the USA, Cultural Facilities has pioneered urban planning in city centres with the gigantic NFL and College Football Stadia moving out of town. New markets are also coming online for sport and place creation. Saudi Arabia is planning a number of enormous sports led projects along with already securing the 2034 Asian Games. Qatar hosts the 2022 World Cup. This all testifies to a keen desire to be creative stewards and worthy hosts for major sports, entertainment, and cultural events. Such wealthy nations, with freedom to develop unencumbered by old structures, can be found looking at global best practice and setting standards for integrated projects and strategic investment, with sport at their heart. This must be for good in the end.

To put principles for ‘place creation’ in summary form, they should to my mind be oriented around Access and Connectivity (to a community), Function and Form (so aesthetics are integral to design), Nature and Nurture (with training offering new opportunities for all), Authenticity and Relevance (for clear thinking to produce a well thought through plan). And ‘place creation’ is almost by definition ready to ask harder, deeper questions than about merely function or finance. It needs to ask about a facility’s capacity to inspire and nurture, to demonstrate and cultivate excellence, to serve and satisfy various tastes and needs, to generate communal respect and foster social harmony and well-being. A ‘good’ and beautiful place can, and will, do all that.

As a path to holistic flourishing, sport is well-placed to meet some of the most urgent needs of ever younger societies around the world. Kicking a ball in a dusty back street should never be underestimated. Lives are found in innocent play and imagined sporting trumps. So, let’s not be dull and say unimaginatively, ‘We need a new football ground’. Let’s imagine bold new community programmes in which the boundaries of sport, entertainment, and culture blur, as they do more and more in our global, interconnected, world. If it’s not irreverent to say so, our new temples of secular, sporting devotion should be as open, flexible, and durable as the great cathedrals and shrines of the past. And, yes, let’s remember, as we saw before, the black in the picture of a Hillsborough disaster can lead to the gold of the acute 1989 Taylor Report on safe stadia and the transformation this has delivered. Hope and sport are after all kissing cousins.

Third, I have become more and more sensitive to the responsibility sport has to impact our planet for good. Globalization and technology have combined to render sport a desirable financial asset. State backed companies in the Gulf have bought into football clubs like Manchester City (City Football, Abu Dhabi), Paris St Germain (Qatar Sports Investments) and Newcastle United (Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia); while China has invested heavily in the Olympic Games and a range of sports assets as part of its international outreach and infrastructure development. This will send shivers down the spine of some. It could, and probably should, be read more positively. Though sport has known more than its fair share of politics and corruption, on a good day the ‘soft power’ it wields is largely wholesome, its insuppressible ability to delight and unite far greater than the evil intent of its users and abusers. And if wealth can be channelled towards multi-use, carbon neutral, venues that are spacious, attractive, and evocative of a world where play is as important as power, what harm is there in that?

Let me end by drawing out one point from the last sentence. To-date, there are few sustainable stadiums in which ecological responsibility is the focal point of their design. This must be legislated for and change quickly. Sport’s global profile means it has a duty to model best practice of every kind. Whether it is the World Cup, Formula I, or the Olympics, the carbon footprint of these events must be monitored, lest the good they do harm our children’s future. Sport matters in society, but we can make it matter more to a wider audience and in doing so inspire future generations to be heathier, whilst breaking down discrimination and barriers as President Mandela hoped.

Michael Pask, Senior Associate, Oxford House, and Founder, Taliesin Advisory