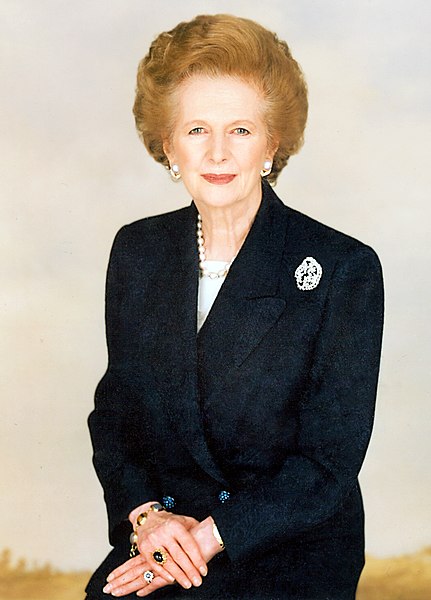

In a world of corrupted ‘news’ (see Weekly Briefing, 5 October 2020) speech writers have a vital role. Their job is to anticipate – and redirect – editorial agendas with timely one-liners. Sir Ronald Millar (1919-1998) – by profession an actor, script writer and dramatist – had been British PM Margaret Thatcher’s (1925-2013) speech writer for seven years when he parodied Christopher Fry’s play The Lady’s Not for Burning (1948) in the ‘Iron Lady’s’ speech to the Conservative Party Conference on 10 October 1980: ‘You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning.’ Sentences that were hailed at the time by supporters as classic symbols of masterful leadership are now synonymous with the essence of Thatcherite conservatism, i.e. bareknuckle Britishness and a ‘free-market’ economy. Apparently, the literary allusion passed Thatcher by when first proposed by Millar: the political potential of the words did not. She thought, ‘You turn if you want to’ would be the headline. How wrong she was! Leaders fail. Messages are poorly delivered and selectively heard. Who’d be a leader today!

Fry’s play The Lady’s Not for Burning is a Three-Act romantic comedy in wry, rhyming prose, set in a small town in 15th century England. Written into and out of the ‘exhaustion and despair’ of a futile second World War, the play is an ironic exposé of false hopes and empty fears. The three central characters are Mr. Tyson the inept town Mayor, who responds with depressing regularity to complaints, ‘It will be looked into all in good time’; Thomas Mendip, a world weary ex-soldier, who tries to persuade an uninterested Tyson that he has killed a wastrel ragamuffin, Skipps, so he can get himself hanged for murder; and, a beguiling beauty, Jennet Jourdemayne, who has been accused of witchcraft by nasty neighbours and looks to Tyson for protection. She it is who is ‘not for burning’. Absurdly, Tyson, who has designs on Jennet for his sons, imprisons Mendip and Jennet together, hoping to overhear an incriminating confession. In the event, their (strikingly philosophical) conversation in Act II is anything but a confession of guilt! The plan fails. Skipps reappears. Mendip and Jennet have fallen in love. The hopes of the Mayor and his amorous off-spring are dashed. But all ends well. Life goes on. Joy returns … and the foul taste of a febrile judiciary lingers. As Fry says of the play, ‘the characters press on to the theme all their divisions and perplexities’. Like an adept script writer, Fry lays claim to the headline, ‘There is no justice in life.’ Leaders beware.

For all its hidden pathos, Fry’s play does not reflect the dark despair of ‘Prison Wall’ fiction. It is more like Marcel Proust’s (1871-1922) mighty novel, A la recherche du Temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time, 1913-27), in which history and ethics are read into biography and irony. In Fry and Proust, memory is the energy of life, for good and ill. Unwittingly, Ronald Millar’s clever parody on Fry’s play is a useful litmus test for leadership. At the time of her speech, Thatcher was facing rising unemployment (from 1.5m in 1979 to 2m by October 1980), angry trade unions and growing social unrest. She was under political pressure from the Labour opposition and ‘Tory wets’, including her predecessor Edward Heath [1916-2005]), to ‘liberalise’ her economic agenda. Her position was clear, ‘The lady’s not for turning.’ To some, this was the height of arrogance and cruelty, to others, the defining moment in an extraordinary leader’s career. What to Fry was a hope, to Thatcher was a vocation. Modern leadership has learned much from Thatcher about ‘messaging’. Life changed by a single letter and a simple phrase.

There is to most of us a fine line between (acceptably) strong leadership and (unacceptably) pig-headed self-confidence. ‘Leaders are wise to listen’, most electors would say; after all, ‘Two heads are better than one’ and ‘Plans are refined by discussion and criticism.’ As if to underline the wisdom of circumspection, the Old Testament Book of Proverbs twice cautions against blindly bashing on: ‘The prudent see danger and take refuge, but the simple keep going and pay the penalty’ (22.3, 27. 12). In other words, those who are ‘not for turning’ hurtle over cliffs, dig deeper holes of debt, destroy love that a little flexibility might save. With ancient wisdom again whispering, ‘He who trusts in himself is a fool’ (Proverbs 28.26). Despite this, the perceived professional (or personal) damage of being ‘weak’ outweighs for many the historically stronger virtues of humility and prudence, viz. in practical terms, listening and negotiating. It used to be said, ‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going.’ Twenty-first century culture is raising global leaders (and followers) more ready to believe: ‘The going’s tough … so get tougher.’ What an unpleasant, violent, competitive, fractious world it makes. Britain under Thatcher was not peaceful. Every indication is COVID is helping to breed a new generation of unlikely, inflexible, demagogic heirs.

The 2012 film The Iron Lady (starring Meryl Streep, Jim Broadbent and Olivia Colman) was not to everyone’s taste. The mind and motivation of an/the ‘Iron Lady’ are hard to capture. Power is a complex compound. As Margaret Thatcher memorably said, ‘Being powerful is like being a lady. If you have to tell people you are, you aren’t’(!). ‘Iron Ladies’ disprove the principle, ‘Power is a matter of physical strength.’ Thatcher could terrify friend and foe: her charm pierce like a rapier and console with a tear. The Prime Minister who took Britain to war over the Falkland Islands (2 April to 14 June 1982) had previously quoted St. Francis of Assisi’s (c.1181-1226) poignant prayer (off a 10x5cm card, which survives) on the steps of 10 Downing Street, after her first General Election victory (3/4 May 1979): ‘Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope.’ Motivation is famously complex; in the politically, socially, and culturally powerful, perhaps especially so.

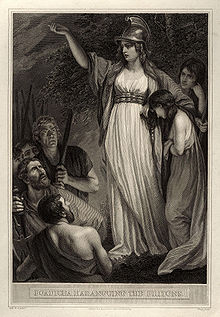

There have been other ‘Iron Ladies’ over the centuries. The Iceni Celt Queen Boudica (or Boadicea; 30-c.60 CE), who harried the invading Roman army in 60 and 61 CE. Imelda Marcos (b. 1929), the corrupt, shoe-loving, ‘First Lady’ of the Philippines (fr. 1965-1986) and four times presidential candidate (after her return from exile in 1991). ‘The Lady’ of modern Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi (b. 1945). There is also today a so-called ‘Iron Lady of Pakistan’, the political activist and media icon Muniba Mazari Baloch (b. 1987), and an Indian ‘Iron Lady of Manipur’, Irom Chanu Sharmila (b. 1972), otherwise known as ‘Mengoubi’ or ‘The Fair One’, who is like Baloch a political activist. To these, Millar’s parody of Fry also applies: ‘These Lady’s not for turning’ with their Thatcher-like single-mindedness and charisma.

So, what can we learn?

First, of course, strength of purpose is not a weakness. The ‘iron’ will of a Winston Churchill (1874-1965) or a St. Mother Teresa (1910-97) can do much good. How much worse our world without Human Rights lobbyists and lawyers, and socio-political activists in India and Pakistan. Whatever we make of Margaret Thatcher and her political vision and legacy, she is a good reminder to leaders not to become addicted to power and popularity nor turn when the going gets tough. But iron can crush, decisiveness be destructive. The issue is: ‘To what ends does strong leadership tend?’ Leadership is assayed by character, not by achievement.

Second, leaders may begin well but end badly, they may begin wise but end foolish. Yes, the exercise of power is a concomitant of leadership and government, but power is always a trust not a right. It is too simplistic to say, ‘Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely’: it is not far-fetched to see wisdom in the advice to a ruler in Proverbs 25.5: ‘[A] throne is established through righteousness’ (viz. justice and doing what is ‘right’). Corruption and injustice eat the legs on which a government and leader stand. The ‘iron’ of leadership is tempered by moral rectitude and consistency. To vote for those without integrity is to lean on a weak wall. We do well to remember, though, hypocrisy and pride stalk newsrooms, boardrooms, the corridors of power … and our homes. Factoring in (inevitable) human flaws in leaders and lead is surely only fair. ‘Messages’ that suggest otherwise are palpably crazy.

Third, Ronald Millar’s brilliant one-liner is a reminder of the power (and importance) of effective communication. Poor PR has crippled most mainstream religions. They have lacked skilled scriptwriters to head off media prejudice and neutralise negative coverage. They have also lacked for exemplary leaders who have known and shown the difference between wise accommodation (to criticism and culture) and foolish accession (to fads, whims and the need to be popular). To followers of the three Abrahamic faiths, God’s word through Isaiah to an embattled King Ahaz should always carry weight: ‘If your faith does not endure, you will not endure’ (Isaiah 7.2). Wisdom knows when to ‘turn’ and when to hold firm: folly, tragically, does not.

Christopher Hancock, Director