Pope John Paul II (1920-2005; r. 1978-2005) was, like his predecessors John XXIII (1881-1963; r. 1958-1963) and Paul VI (1897-1963; r. 1963-1978), committed to the Catholic Church’s involvement in – if not direction of – international affairs. To that end, he and his staff cultivated and (usually) retained close connections with numerous governments and government agencies worldwide. In contrast to previous Popes, John Paul II expanded his ‘concordat’ activity to continents and countries the papacy had had little, if any, previous relationship with. This work grew after the fall of communism in 1989. New ‘concordats’ were concluded with Albania, Croatia, Slovenia and German Länder that had belonged to the German Democratic Republic. Agreements were reached with Israel (1993 and 1997), the Palestine Liberation Organization (2000), Morocco, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, and the Organization for African Unity. John Paul II’s work for global peace and inter-religious understanding remains a central pillar of his (now increasingly controversial) legacy. But, how much good has John Paul II’s international labour bequeathed to his successors, let alone to the world? That is the question driving this Briefing. To those who believe their lives unaffected, I would simply say, ‘Read on and think again.’

John Paul II’s international vision: the early years

John Paul II’s global vision was clear from the start. His later extensive travels confirmed this and sealed his hope that the Church be the ‘instrument of peace’ for which Francis of Assisi (b. ca. 1181 – d. 1226) prayed. In an address at Belvedere Palace, Warsaw, in June 1979, he urged those present to see that states can and must work together: this will be of benefit to them and to humanity at large. Prior to this, he had already called on totalitarian states to respect freedom of religion and conscience. He repeated this call in his Encyclical Redemptor Hominis (March 1979). There, life is a ‘magnificent patrimony of the human spirit … manifested in all religions, cultures and ideological conceptions’. Throughout his pontificate, John Paul II spoke of God’s Spirit being at work in all religions. Inter-religious and ecumenical activity is thus to be undertaken in a spirit of ‘openness, rapprochement, [and] readiness to dialogue’. In October 1979, John Paul II issued his Apostolic Exhortation Catechesi Tradendae. This addressed the Catholic Church’s role in a religiously plural world. In keeping with the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), Bishops are charged with nurturing ecumenical relations (esp. catechesis) to promote God’s love and mission to the world: this remains the beating heart of John Paul II’s global vision.

John Paul II’s international work is worth recalling, however much the world has changed. Six themes stand out.

i. Central to John Paul II’s ecumenical activity is his encouragement of close cooperation between the three ‘Abrahamic’ faiths (Judaism, Islam and Christianity). From the start of his pontificate, John Paul II sought to improve relations between Christianity and Judaism: addressing the World Jewish Congress in 1979, he spoke of his hope to develop greater harmony between the three world religions that claim Jerusalem as their spiritual home. At a general audience in Rome in 1980, he expressed his conviction that Catholic mission in Africa must dialogue with both Islam and indigenous ‘animist’ religions. In Brazil, he urged cooperation within ‘the Jewish-Christian brotherhood’ in order to deepen consciousness of a shared biblical heritage, without ‘disguising the differences that separate us’. The same year, he spoke in France of the religious identity Judaism and Catholicism share, and of the way that relation could and should be encouraged through greater mutual understanding.

ii. John Paul II’s focus was humanity, not just Christians or people of faith. In an early address to Japanese diplomats, he expressed his conviction that as a ‘spiritual’ entity the Church is by nature ‘united to every people, to every nation’, and therefore it has a duty to serve others in the cause of justice and peace. As Pope, his bi-lateral dialogues with governments were inspired by his commitment to humanity per se and guiding vision for the ‘common good’. The Church is not, he told diplomats in Rome in 1982, ‘foreign to any culture … civilization … ethnic or social tradition’, nor ‘does it consider any people foreign’. The same year, he spoke in Bergamo of the distinct identities and unique vocations of the Church and State. But, because ‘the political community and public authority are founded on human nature’, they both ‘belong to the order foreseen by God’. Speaking in America in 1980 and Japan in 1981, he pressed for positive relations between Anglicans, Lutherans, Reformed Churches, Methodists, and Disciples of Christ (and others) in order to realize their fundamental unity.

iii. By encouraging Catholics to see the Church as commissioned by God to protect the dignity and rights of all people, John Paul II gave impetus to discussion and defense of Human Rights. More generally, he was in the forefront of critical thinking about ‘ethical’ foreign policy. To intervene internationally, the Pope said in Spain in 1982, required an ethical presupposition and ‘full realization of God’s plan in history’, he told delegates at the Bishops’ Conference on Jewish-Catholic relations in March 1982. This theme recurs in his address to Jewish and Muslim leaders in Scotland in June of that year, and later in South Korea. Diversity in religious and ethical belief is, he maintained, a spur to true dialogue. But John Paul II set boundaries around the Church’s responsibility and activity. In addresses in Austria (1983) and the Netherlands (1985), the role of the State viz-à-viz politics and economics is celebrated, as is that of the Church to fight for ‘true freedom’ and to ‘defend[s] the inalienable rights of the person’. The Church had, the Pope maintained, an ethical mandate from God to help those whose Human Rights are violated or who suffer from war, injustice, famine, drought, and natural disasters. It is this the Church brings to (what John Paul II termed) ‘the international game’ for the ‘common good’. This perspective was reiterated to the diplomatic corps in 1983 and the Bishops of Chile in 1987. During his pastoral visit to Switzerland in 1984, he went further and called on the laity to engage in earthly affairs, since day-to-day they, and the activities of every kind they participate in, are God’s incarnate presence in society.

iv. John Paul II’s internationalism led him to dialogue with some unlikely communities. In June 1984, he met leaders of the Swiss [Reformed] Evangelical Churches and members of the Swiss Bishops’ Conference. In an act of ‘common celebration’, their discussions created a ‘communion of thought’ doctrinally, and a shared will to fulfil Christ’s great commission. In 1984, the Secretariat for Non-Christians (founded by Pope Paul VI in 1965) launched a new initiative in religious pluralism. John Paul II’s relational approach to diplomacy was founded on his desire for, and ability to develop, trust. To develop realistic and effective dialogue the Church must, he stressed, establish ‘what is lacking in nations and blocs that fail to establish their relations on trust’. In 1985, the Pope travelled to Africa. Invited by King Hassan II of Morocco (1929-1999; r. 1961-1999), he spoke to Muslim youth, telling them: ‘Respect and dialogue require reciprocity in all areas, especially with regard to fundamental freedoms and, more particularly, religious freedom.’ In April 1986, he visited a synagogue in Rome, and in October of that year summoned religious leaders to Assisi to pray for world peace. Despite their differences, prayer was, he declared, a path for all people to connect with a power greater than humanity and humanity’s capacity to comprehend. Shortly beforehand, when in India, he had similarly called for religions to cooperate. Inter-religious collaboration must, he said, work ‘to eliminate hunger, poverty, ignorance, persecution, discrimination and every form of enslavement of the human spirit’. In short, John Paul II extended the scope of the Church’s historic engagement with communities, faiths, and world issues.

v. John Paul II’s quest for what he called a ‘true international system’ led him to speak on a number of occasions about three inter-connected issues; namely, the role of ‘superpowers’, the threat of nuclear weapons and the needs of developing countries. These themes appear in his first address to the United Nations in October 1979, and many years later in his Papal Encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (December 1987). On a visit to the USA and Canada in September 1987 he promoted inter-religious dialogue and spoke of his own appreciation for the Buddhist community’s way of life, based, as he said, ‘on compassion, loving kindness and the desire for peace, prosperity and harmony for all living beings’. He also praised Islam’s teaching on life as a divine gift, Hinduism’s quest for inner peace and global harmony, and Judaism’s fight against bigotry. Time and again he appealed to the three Abrahamic faiths to work together in the cause of peace and the ‘common good’. As he told representatives of Jewish organizations in the United States, ‘we are called to collaborate in service and to unite in a common cause’. At a meeting of Muslims and Christians in October 1988, he urged those present to show the world ‘the path to harmony and mutual respect’. In subsequent meetings with members of the Jewish community in Austria (1988), France (1988) and Brazil (1991), he again pressed for reconciliation; not least, via the Commission for Religious Relations with Judaism and International Catholic-Jewish Liaison Committee. In his Apostolic Exhortation Christifidelis Laici (December 1988) he noted with concern an increase in indifferentism, secularism and atheism that he connected with prosperity and consumerism. Few now doubt that John Paul II’s internationalism and openness to other faiths was shaped by his sense of call and Christian faith: these were the beginning and end of all his endeavour.

vi. Another key element in John Paul II’s international work (before the end of communism) were his institutionalizing initiatives. As we have seen, he re-named Pope Paul VI’s 1964 ‘Secretariat for Non-Christians’ a ‘Dicastery for Inter-Religious Dialogue’ in the Apostolic Constitution Pastor Bonus (1988). The aim was to promote and regulate relations with people and groups that are not ‘Christian’ but are in some way still ‘religious’. He similarly reinvigorated the ‘Commission for Religious Relations with Muslims’ that Pope Paul VI had set up in 1974. Though originally focused on Catholic-Muslim relations, the Council’s work turned to include collaboration with other Christian bodies. John Paul II’s desire to link thought to practical, institutional, action is clear. Speaking to religious leaders in Jakarta in October 1989, he urged a practical dialogue ‘to appreciate the spiritual values of others’. In the same vein, he told Zambian diplomats in 1989 that cooperation between developed and developing nations was vital if Human Rights were to be ‘an integral part of an environment that must be humanised’. To John Paul II, institutional forms provided an effective medium for lasting change.

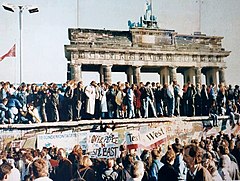

After the fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall and end of Eastern bloc communism in November 1989 changed the world: they also served to reorient John Paul II’s pontificate. Contrary to the impression sometimes given, John Paul II’s international vision is clearer before 1989 than after. For the remainder of this Briefing, I want to look at five aspects of John Paul II’s global ministry after 1989 and consider their lasting impact. It is a story of continuity and striking discontinuity.

i. His perspective after 1989 was as much on what had made Europe great as what would make a reunited Europe great again. Mindful of its primary spiritual vocation, the Church is, he said, to be ‘a courageous spokesman for those values and traditions which once shaped Europe’. It is the duty of the Holy See, he began to say more loudly, to awaken consciences and encourage fraternity, but to do so without temporal ambition. Papal diplomacy is to build bridges between countries, and thus foster friendship between peoples. Fearful, perhaps, of the dissolution of a society shaken by the political sea-change that had occurred in the former Soviet Union and its dependent states, John Paul II seems to turn inwards to ensure the Church is a solid bastion against social decay and political mayhem. The conservatism for which he is now best known was, I suggest, reinvigorated by the end of communism.

ii. The need for the Church to be an ‘instrument of peace’ in a multi-religious, politically volatile world also emerges strongly in Pope John Paul II’s teaching after the fall of the Berlin Wall. His attention turns inwards to the life and coherence of Catholic Faith (in a world where faith was – and is – under increasing pressure) and outwards to the Church’s relationship to other faiths and non-Western cultural matrices. The 1990 Papal Encyclical Redemptoris Missio addressed the complex issue of the inculturation of the Christian gospel. The Encyclical encourages a parallel process in which the Faith of the Church and local culture are both factored in to promote fruitful inter-religious dialogue. Religiosity is now set in the broad context of human history and global culture. As John Paul II pointed out in a speech in Mexico in 1990, humanity is located in, and passes through, different stages of development and dynamic contexts (viz. the international and the ecumenical, the political and diplomatic, the spiritual and temporal). Returning to themes addressed before 1989, he focuses on the place of, and relationship between, the Abrahamic faiths in world affairs. In Malta and at a general audience the same year, celebrated positive progress on controversial issues in inter-religious dialogue and reaffirmed his hope that the Church would always be an agent of fraternity and mutual respect. Greeting members of the dialogue sub-unit of the World Council of Churches in June 1991, he reiterated his optimism about the progress being made in inter-religious dialogue, which, he said, serves to ‘unite[s] us in holy respect before the divine mystery that guides human destiny’. To many observers, the subsequent conflict in the Gulf and the rise of radical Islamism now render John Paul’s optimism misguided.

iii. The reality of cultural transformation and the need for its reconstruction in Europe after the end of communism are other key emphases in John Paul II’s thought and teaching. Yes, we see the same emphasis on the duty of the Catholic Church to ‘reach out to the needs of the whole Church and preach the Gospel everywhere’ (Apostolic Exhortation Pastores Dabo Vobis, 1992). We also find in his presentation to representatives of the three Abrahamic faiths at Assisi in January 1993 an exhortation to engage in the reconstruction of Europe. Likewise, addressing a gathering in Slovakia in July 1995 he urged greater tolerance towards minority communities, while the Encyclical Ut Unum Sint (May 1995) teaches a ‘correct, loyal and understandable’ account of Christian faith and experience and sensitivity to the history, memory, and suffering of others. The shadow of the Holocaust and war in the former Yugoslavia fall across much of John Paul II’s speaking and writing in the mid- to late-90s. In June 1996, he urged a German audience to see an intrinsic connection between Judaism and Catholicism. Likewise, speaking in Sarajevo in April 1997, he said Christian charity will always seek to nurture understanding between cultures and religions, including between the Orthodox churches and other Christian brothers and sisters. As elsewhere, he told general audiences in 1997 and 1998, the revivification of Europe faith and culture depended on an intensification of ecumenism and dialogue. In Europe, he said, this is now like engaging Asian cultures ‘which are deeply imbued with a religious spirit’ and ‘traditional African religions, which are for many peoples a source of wisdom and life’. In March 1998, the Vatican’s Commission for Religious Relations with Judaism published We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah, based, in part, on the Declaration Nostra Aetate. In the accompanying letter to this reflection, the Pontiff expressed his longing that such a horror would never be repeated.

iv. There are clear signs of continuity and discontinuity in John Paul II’s international and ecumenical activity in the last years of his pontificate. In his Apostolic Exhortation Ecclesia in Asia of 1999, for example, he describes the need and the challenge of ecumenism in Asia, where unity had to be restored ‘among those who have accepted Jesus Christ as Lord in faith, so that all peoples may be brought together by the grace of God’. To advance this, he proposed the creation of centres for prayer and dialogue in seminaries and other religious venues. With global tension and anti-Semitism on the rise, he told a general audience in 1999, Jews are ‘elder brothers’ and the biblical sources that Jews and Christians share are indispensable elements for living and deepening faith. In Mexico the same year, he again spoke of humanity passing through different ‘fields’ (ecumenical, international, and the ‘powers of this world’), but now urged greater understanding between Jews and Muslims.

These emphases continue in the 21st century. Speaking to Israeli rabbis in 2000 and 2004, he urged greater contact between Christians and Jews to promote greater mutual respect and cooperation and to grow ‘ever deeper understanding of the historical and theological relationship between our respective religious heritages’. The official dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Chief Rabbis of Israel was, he said, a sign of great hope. Likewise, during an inter-religious meeting at the Pontifical Institute of Notre Dame in Jerusalem in early 2000, the Pope urged a continuation of sincere and fruitful inter-religious dialogue with Jews and Muslims since ‘there is good and holy in the teachings of each’. However, in the welcome ceremony in Bethlehem in 2000, John Paul II assured he Palestinian audience that the Holy See had always recognized their natural right to a homeland and welcomed the UN Resolution on Bethlehem (November 2000), in which the international community pledged itself to seek peace in the Holy Land. In May 2001, John Paul II prayed for the first time in a mosque (the Umayyad Mosque, Damascus) and expressed his hope that Muslims and Christians would pursue respectful dialogue and never again be ‘communities in conflict’. The optimism evident here is again indicative to some mere wishful thinking.

v. As indicated at the start, John Paul II reached out to communities hitherto beyond papal activity. In 2002, he invited religious leaders to join him in Assisi. Those attending included the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, eleven other Orthodox Patriarchs and a party representing the Patriarch of Moscow. Present were also representatives from Reformed churches, Judaism, Islam (from Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Egypt, Libya, the Philippines, and Turkey), Buddhists, Hindus, Jains, Zoroastrians, Confucians, animists from Africa and various Christian denominations. The Pope again pleaded for peace and a bearing witness together to the ‘common longing for a more just and united world’. He prayed for respect for and recognition of the dignity, rights, needs and responsibilities of all people. The same year he visited Azerbaijan and praised the work of religious leaders in promoting tolerance and mutual understanding. In 2003, the Apostolic Exhortations Pastores Gregis and Ecclesia in Europa stressed the importance of interreligious dialogue for everyday life and the value of relations with Jews and Muslims. European institutions were exhorted to promote religious freedom internally and to work for it internationally, especially where Christians were a minority. A similar appeal was made to the Council of European Bishops’ Conferences in 2004, where John Paul II called for the reception and integration of populations and communities with different religious traditions.

Whatever historians and critics ultimately make of John Paul II’s pontificate, there can be little doubt that he was a spiritual leader with a remarkable presence and global profile. In his international, ecumenical, and inter-religious work he balanced tact with directness, the strong arm of papal leadership with a friendly embrace for the fearful and wary. He was both ‘spiritual’ and ‘worldly’. He was a bright light in an increasingly dark world spiritually and politically. Without wavering from his deeply traditional Catholic identity, he brought together nations, races, peoples, and religions, recognising them all as sons and daughters of God. Though he resisted politicizing the church, he was an advocate of social renewal and fought the spirit and legacy of communism, and the plague of injustice, to his dying day.

Dr Pablo Baisotti – Oxford House Associate