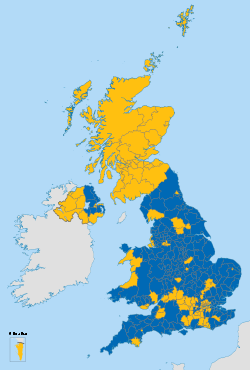

On 23 June 2016, 52% of the British electorate voted in a referendum to leave the EU. After four years of tense negotiation and heated debate, of grandstanding and brinkmanship in Westminster and Brussels (and in the Parliaments of EU member states), the terms of the UK’s withdrawal were confirmed. The land border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and the status of EU regulation of goods, services, and standards (including workers’ rights) were major sticking points. On 23 January 2020, the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act received Royal Assent. On 31 January 2020, the UK entered a ‘transition (or ‘implementation’) period’, during which it ceased to be a member of the European Parliament but continued in the EU Single Market and Customs Union (and was subject to EU regulation). At 11pm on 31 December 2020 this ‘transition period’ finally ended, and the UK left the Single Market and Customs Union.

The referendum result has been put into effect. Many loose ends remain. Agreements on the adequacy of data protection and many aspects of financial services are yet to be reached. Members of the UK’s fishing industry are particularly unhappy about the terms of the deal the British PM Boris Johnson signed. But the full implications (for good and ill) of Britain’s departure from the EU will only emerge over time. As the protracted – sometimes bitter – negotiations revealed, there were, and are, many sides to the debate about the benefit/s and threat/s of a changed relationship between the UK and EU. Much ink has been spilled on the politics of Brexit. My interest here is more practical and personal.

Prior to entering Parliament as a Conservative MP in 2010, I spent much of my working life in East Africa engaged in international trade. Since standing down from Parliament before the 2019 General Election, I have watched the progress of Britain’s departure from Europe with interest. I confess reports of UK-EU discussions of their future trading relations, have left me both amused and bemused! Most of the goods I dealt with in East Africa were shipped between countries, none of which were EU member states. When I read of difficulties exporters and importers have had with new customs regulations (and the accompanying paperwork) or see on the news queues of freight lorries jammed on the M20 in Kent or parked up on airfields nearby (in so-called ‘Operation Stack’), I confess to being not in the least surprised or shocked. On a number of occasions (indeed in the past few days) I have had to rush new, or corrected, paperwork to a port because rules have changed with little notice. You become used to it. That said, let’s be clear, the (relatively) seamless trade of the EU Customs Union (established 1968) and Single Market (established 1993) does have advantages – and both the UK and the EU may miss them.

To pick up the last point. Much of the focus on the UK leaving the EU has been on the effect this will have on trade and investment; whereas, I suggest, other consequences may be greater. Trade and investment between the UK and EU will almost certainly settle in the next decade or so into a new normal, perhaps at a lower level than hitherto, but perhaps not. We simply don’t know. What we do know, though, is that America’s economic weight in the past twenty years or so has been the result less of its industrial giants like GE or Boeing, and more of its newer digital behemoths (like Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, etc). Viewed in this light, the UK’s historic strength in services (especially in banking, life sciences and digital innovation) may over time supplement a decline in trade in goods.

If we focus in on the realities of trading, other, more general, often unacknowledged, factors come into play as we ponder Britain’s departure from the EU. These factors are part of an intricate pattern relations (so vital to servicing business), which have developed in Britain’s trading relationship to the EU since it first joined on 1 January 1973. These factors can be categorised as official, formal, and personal. I look at them briefly in turn in what follows.

First, it is at the official level that differences in UK-EU relations will be most obvious, most quickly. After 31 December 2020, the UK is technically a ‘third country’ as far as the EU is concerned. The relationship between the UK and EU Boris Johnson signed off on in December 2020 is a close one; closer than with any other country except those in EFTA (Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein) and Switzerland. But Britain is still designated a ‘third country’; that is, it relates to the EU on the same basis as the USA, China, Malawi, Uruguay and 150+ other countries. Under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement (and Britain’s prior decision to leave the EU), UK ministers and other government officials will no longer have regular and guaranteed access to their counterparts in the EU. That may initially be something of a relief (!): it certainly gives more time for developed and developing contact with other countries. But, in the long term, it could lead to increased distance of every kind between the UK and its nearest neighbours. That would be dangerous and sad.

Leaving aside the (hopefully) passing squall over the position of the EU Ambassador, there are other institutions in which official relations with and within Europe are expressed and can be secured; perhaps even enhanced in the future. The most significant is, surely, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), founded in 1949 as a bulwark of peace and pillar of the Western Alliance. For much of its life NATO has functioned well; so well, some might say, its success has bred complacency. Peace and security have been taken for granted by those of us born after WW II. In the debate over Brexit, much was made of how the EU (and its former post-War incarnations) protected peace in Europe. This is unimaginable without the security umbrella of NATO. From its position outside the EU, the UK has, I believe, a greater responsibility to encourage and strengthen the Western Alliance – an alliance, we should be clear, which is first and foremost defensive of its members. The UK can, I would say, make no greater contribution to the rest of Europe than this going forward.

Post Brexit, the UK remains a member of two other key official European bodies, the Council of Europe (proposed by Churchill in 1943 and formed finally in 1949) and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (established in 1975). Both bodies admit UK parliamentarians as active participants. The European Convention on Human Rights and its associated Court arose from the Council of Europe. By taking an active role in these (and other) organisations, the UK can act to both support and enhance their work while at the same time safeguarding our place and credibility in Europe. It is these inter-governmental bodies which are more often agencies of harmony and co-operation than supra-governmental megaliths that seem to some to endanger national sovereignty and sensitive cultural ecosystems.

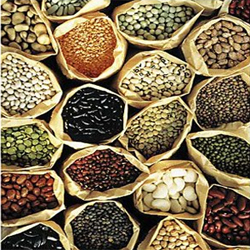

Second, there are also many ways in which formal relationships can be enhanced. To illustrate. Much of the detailed work in ensuring common standards for business (for instance, in the field of safety and environmental protection) is carried out by international trade organisations. By playing a full and constructive part in them, UK businesses can enhance their reputation and be a wholesome influence on determining standards which in time will affect us all. I found chairing a trade association a delight. It afforded lifelong friendships, exposure to valuable expertise and access to new business!

Third, as this last point suggests, it is ultimately personal connections which will shape the UK’s future relationship to the EU. But there are practical hurdles to cross. The end of freedom of movement makes it harder for UK citizens to work in the EU (and vice versa), but it will still be possible to travel without visas (for stays under 90 days) and to do international business with companies and individuals that are already well-known. To those of us old enough, it feels a little like stepping back in time. I remember going to work for a Swiss hotel in 1976: I needed a work permit, was X-rayed for tuberculosis at the Swiss border and required to check in regularly with the police. These were minor inconveniences when compared to my enjoyment. I made lasting friendships … and my German still sounds rather Swiss.

I am very aware that my freedom to travel and work abroad then was a privilege. It became much easier for many with the freedom of movement, which we have now lost. We can learn so much through international exchange. Brexit must not mean a cultural, relational exit from Europe. I regret the UK’s decision to leave the Erasmus+ student exchange scheme. The Turing Scheme that replaces Erasmus+ could have been additional. But now that the decision has been made, I would like to see the Turing Scheme accessible to as many young people as possible.

As indicated at the outset, I have tried to avoid politics in this Briefing. But, if we needed reminding, America has shown this week just how quickly a change of leader or party can affect political weather. Last week the US was outside the Paris Climate Agreement and withdrawing from the World Health Organisation: this week, it is back in both. I do not mean by this to imply that I think the UK as a whole will seek soon to return to the EU (although Scotland probably would if it left the United Kingdom, and Northern Ireland would if a border poll reunified the island of Ireland). But I do believe a future UK Government may well seek a closer relationship with Europe than the December 2020 Treaty creates. Meanwhile, no speculation is needed to see the value of close, open, honest relations between the UK and EU in the future. As with all relationships we value, they do not just happen. They are constantly under threat, always in need of attention and require much love and labour – in this case, not only by governments and government departments but by citizens in the UK and the EU.

Official, formal, or personal? They are all vital parts of the UK’s future relation to the EU.

Jeremy Lefroy, Associate