It’s hard for people of my age to believe Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (b. 1930; General Secretary 1985-1991, Pres. 1990-1991) resigned 30 years ago this Christmas. His resignation signaled the end of the Soviet era and of its hegemony in Eastern Europe. As Chairman of the Supreme Soviet (25 May 1989 to 15 March 1990) and President of the Soviet Union (15 March 1990 to 25 December 1991), Gorbachev reframed the USSR and expedited the end to its protracted ‘Cold War’ (1947 to 3 December 1989) with the ‘Western Alliance’. The fact we are in a new era of East-West tension casts the events of 30 years ago into a new, cold light.

Is it really thirty years since the Russian flag was raised over the Kremlin on New Year’s Eve 1991? More tellingly, with Russia reverting to old style, adversarial totalitarianism under President Vladimir Putin (b. 1952; PM 2008-2012; Pres. 1999-2000, 2000-2008, 2012-present), how much of that part of the history of East-West relations is worth recalling, let alone celebrating today? Yes, many of the protest movements across Central and Eastern Europe in 1989 have left a legacy of democracy and stability. But the massing of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border, and the accommodation – if not encouragement – by Putin of the anti-Western belligerence of Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko (b. 1954; Pres. 1994-present), suggest many Russians may not be celebrating – or want to remember – the events of thirty years ago when the world said, No, to Soviet oppression and violence.

History is an invaluable aid to recollection, celebration, and an all too often justified act of self-criticism. In this Briefing I want to look back on events 30 years ago inside and outside the Soviet Union as its days were numbered, and its nefarious deeds became known. It was my privilege to be close to leading Soviet and Western actors in the drama that unfolded.

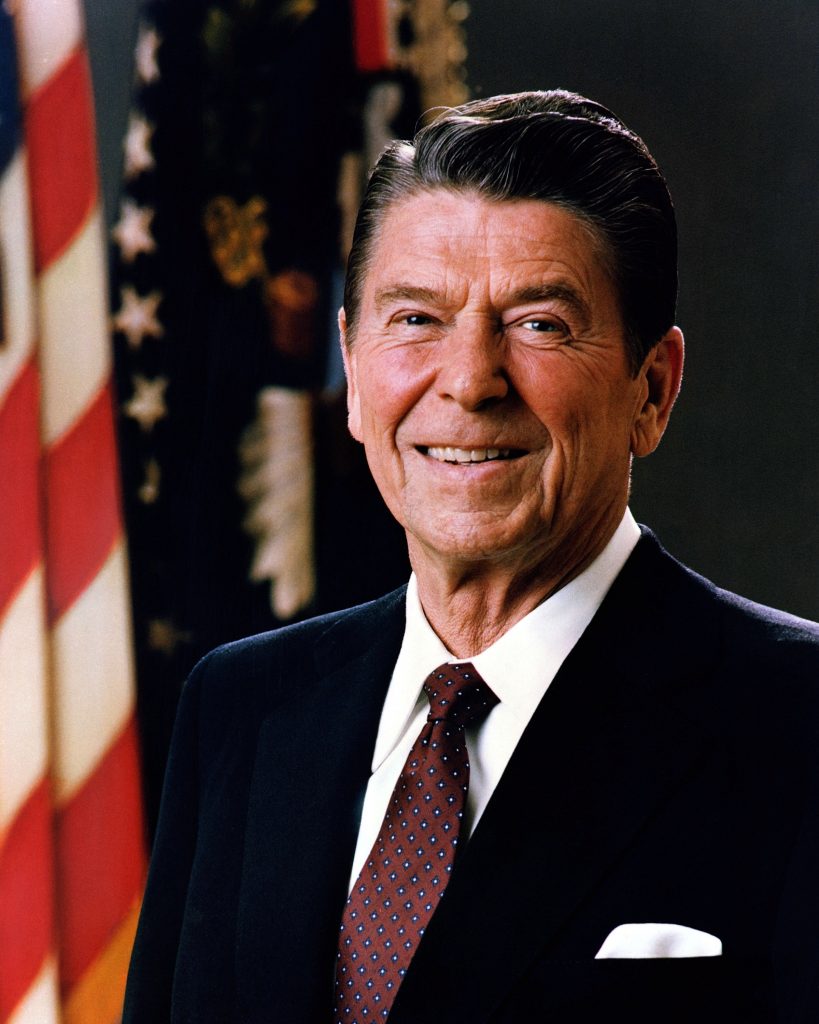

Prior to the resignation of Gorbachev and raising of the Russian flag, I was working for an organization close to President Reagan’s (1911-2004; Pres. 1981-1989) White House. Our mission was to secure the release of Soviet ‘prisoners of conscience’ from the miseries of the Gulag. In time I transitioned to working for the distinguished Republican Congressman Frank Wolf (b. 1939; Cong. 1981-2015), who was tireless in the cause of political and religious freedom. President Reagan was a staunch ally in defending Human Rights. From the time of the historic ‘Geneva Summit’ on 19/20 November 1985 (when Reagan and Gorbachev met for the first time to discuss international relations and the arms race), the President would carry a card in his pocket with the names of documented ‘prisoners of conscience’ on it. At the end of their regular meetings, Reagan would produce the card and raise specific cases of Jewish ‘refuseniks’, Christian activists, and political, intellectual and social ‘dissidents’. While the US and USSR debated arms control and economic cooperation, the plight of ‘prisoners of conscience’ was not forgotten. And, as we soon discovered, shining a light on the Gulag expedited the release of some of those held. Good was not ineffective.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. On 7 December 1988, then General Secretary Gorbachev reported to the United Nations, ‘[T]here are now no people in places of imprisonment in the country who have been sentenced for their political or religious convictions’. But the terms under which a person was imprisoned were disputed. Gorbachev’s claim related to those convicted of ‘anti-Soviet agitation’ and ‘slander’, as prescribed in Articles 70 and 190 of the Soviet Penal Code. Western observers knew of people who had been imprisoned for trying to emigrate (due to political and religious pressure). These and other political or religious charges were not covered by the statistics Gorbachev cited. At the time, two dozen or so of these ‘prisoners of conscience’ were thought to be held in the infamous Perm 35 labor camp in the Ural Mountains. As the little card in Reagan’s pocket reminded him, his staff, and Soviet officials, history is an accumulation of biographies. Individuals and individual behavior ultimately determine the destiny of countries and communities.

One individual from that era, who over the years I have got to know well, is the distinguished theoretical physicist and Human Rights activist Mikhail Kazachkov (b. 1944). After graduating from Leningrad State University in 1967, Kazachkov joined the Department of Theoretical Physics at the leading research facility of the National Academy of Science in his native Leningrad. He made certain he stuck to fundamental research carefully avoiding any classified work. Well-established in his field, and highly regarded internationally, in 1975 Kazachkov applied for an exit visa to emigrate to the US. Ten days after his application was submitted, he was arrested by the KGB and sent to the Gulag (twice to Perm 35) as a political ‘dissident’. He was moved between ‘political’ penitentiaries for fifteen years. Long before the release in 1986 of the Jewish ‘refusenik’ Natan Sharansky (b. 1948), who went on to become a prominent Israeli politician, Perm 35 was infamous for its brutality and freezing isolation cells (cf. Mike Edwards, ‘The Last Days of the Gulag’, National Geographic, March 1990). Unlike many, Kazachkov survived and was released at the end of 1990. In July 1991 all charges against him were withdrawn corpus delicti (viz. no crime had been committed).

Kazachkov’s story sheds light – encouraging light – on the last days of that brutal Soviet era. There were thousands of battered and bruised ‘prisoners of conscience’ in the Gulag, many of whom died or developed serious mental problems. Since his release in 1991, Kazachkov has lived and worked in the US as an author, advisor, activist and academic, campaigning tirelessly with others in the cause of Human Rights and religious freedom. Kazachkov’s story is a vital, seasonal, reminder of the good gifts these are, and of the impact courageous individuals can have wherever they live.

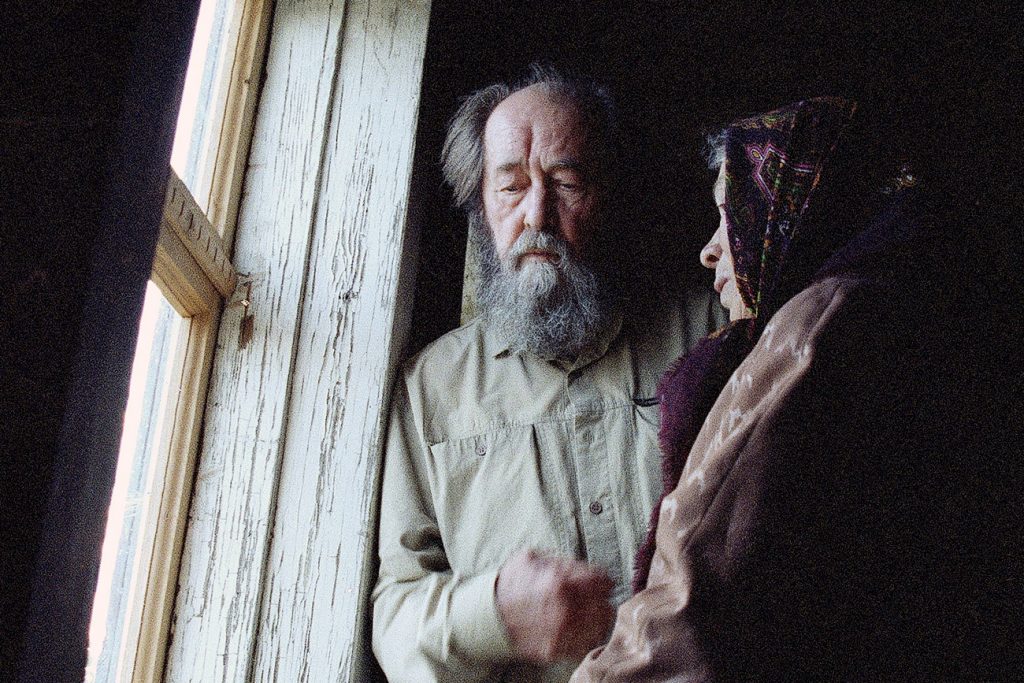

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) (AP Photo/Boris Kydryavov)

There are other individuals we should honor at this anniversary. In the new spirit of glasnost (Lit. openness) and perestroika (viz. reformed systems and economic progress) Gorbachev encouraged, New York Times columnist (and former Executive Editor) A.M. Rosenthal (1922-2006) was granted permission to visit and report on Perm 35. On the day Gorbachev told the UN there were ‘no people in places of imprisonment in the country who have been sentenced for their political or religious convictions’, Rosenthal was in Perm 35. He found conditions dire and access to some prisoners forbidden, Kazachkov among them. Isolated and realizing Rosenthal was being blocked from seeing him, Kazachkov smashed a window and shouted, ‘We want to see you!’, before being brutally dragged away by guards. Rosenthal wrote of this ‘Man in the Window’ many times (New York Times, 13 December 1988, 7 February 1989, 18 August 1989, 16 October 1990, 5 February 1991, and 2 May 1991), who it transpired Human Rights workers had encouraged him to see. Another of what the great literary ‘dissident’ Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) would call the ‘big lies’ of Soviet ideology was exposed on that day.

In time, Kazachkov joined the efforts of former dissidents – including fellow scientists Andrei Sakharov (1921-1989) and, until recently, Sergei Kovalev (1930-2021) – who campaigned for Human and Civil Rights in a state Gorbachev and his heirs claimed to reform. Little has changed, it seems. Russia under President Putin – with, note, more political prisoners today than pre-Gorbachev – is a stark reminder of how much remains unclear and unfinished from the events of 30 years ago.

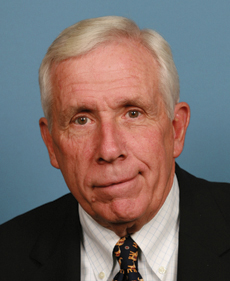

Rosenthal wasn’t the only Westerner to visit Perm 35 in those early years. Frank Wolf and another Congressman known for his Human and Civil Rights advocacy, Chris Smith (b. 1953; repr. 1981), pressed for close, and continued, monitoring of Soviet life. As a young staffer, I was asked by Congressman Wolf to get permission for them to visit Perm 35, with a view to securing the release of its last twenty-four prisoners and closure of the camp. Access to the camp was granted, in part because Wolf was a pivotal voice in Gorbachev’s campaign to gain ‘Most-Favored-Nation’ trade status for the USSR. Wolf and Smith would be the first US officials to enter the Gulag. Much interest inside and outside the USSR surrounded the trip. I travelled to Moscow a few days before the Congressmen. Soon after their arrival, they were informed by a Foreign Ministry official, Anatoly Adamishin (b. 1934), who would go on to become Russia’s Ambassador to the UK (1994-1997), that difficulties had arisen, and a short postponement was necessary. The Congressmen were on a tight schedule. The visit to Perm 35 hung by a thread. Thanks to a controlled leak by the US Embassy of Wolf’s threat that night to campaign against MFN status, I was awakened next morning in my hotel by a call from the Soviet Foreign Ministry: difficulties had been resolved, the visit to the labor camp could proceed! It was an early lesson for me in strong politics and skillful diplomacy. Like Rosenthal, Wolf and Smith never wavered in their view, some things are worth fighting for.

Congressman Frank Wolf (b. 1939; Cong. 1981-2015)

With State Department translator Rich Stephenson, the Congressmen met every prisoner, except Kazachkov, who had been deliberately moved to a prison 200 miles away. They heard the inmates’ stories and reviewed camp conditions. They then demanded to see Kazachkov. Surprised KGB agents acceded and, carrying an old video camera to record the meeting, they set off on bad roads into the wild to meet ‘The Man in the Window’. At their follow-up press conference in Moscow, the Congressmen identified Kazachkov and a few others as political prisoners and issued their demand for Perm 35 to be closed and its prisoners released – over the next year they were. Meanwhile, Kazachkov was moved to the political wing of Chistopol Prison (N.B. his charge was ‘high treason’ for trying to emigrate in 1975). He remained there until his release on 1 November 1990. The political wing of Chistopol closed when he left. Perm 35 remained open but had no more ‘prisoners of conscience’. Journeys ‘behind enemy lines’ are important: they express humane solidarity with those who suffer for speaking truth to oppressive state powers. We need to make more of them.

Kazachkov has over the years shown exceptional courage, clarity, insight and tenacity. For the remainder of this Briefing, I want to reflect on his life and thought and their relevance to the 30th anniversary of the end of the Soviet Union. A number of strands deserve note: these are drawn from events and from the draft of a book by Kazachkov (soon to be published in Russia), which he has kindly shared with me.

First, Kazachkov loves his homeland but from an early age recognized its flaws. His book is about his first ‘two lives’, from his childhood and education to his release from Chistopol. Like Solzhenitsyn, he predicted the demise of the Soviet system but made clear to the KGB he had no intention of renouncing his Soviet citizenship, even if he made a life (his ‘third life’) elsewhere. He was drawn to America from an early age, but says that by 1987, ‘I knew once the Soviet Union collapsed Russia was going to be my “theater of operations,” but the “base” had to be in the U.S.’ He needed his Soviet (and later Russian) citizenship for this campaign. Kazachkov’s sense of ‘dual identity’ is not unique in present day Russia: ambivalence about the Putin regime is found in its expatriate supporters and in resident Russian patriots.

Second, Kazachkov critiques the present in the light of the past. Fluent in English, and with a deep knowledge of Russian history and culture, Kazachkov processes the present state of Russian politics from an informed cross-cultural perspective. On his release from Chistopol, he visited Europe and the US in early 1991 and swiftly joined forces with fellow dissidents, former cell mates, and his friends Kovalev and Sharansky, to campaign for Human Rights and democracy in their homeland. The issue for Kazachkov was not merely recovery from 70 years of totalitarian rule but revisiting 1000 years of Russian history and culture that impeded the adoption of democratic values. History was, and is, for him a mirror in which to see the present more clearly. His early meetings with US officials and public presentations during his two-year Visiting Fellowship at Harvard Law School were frank and realistic: the former USSR needed help transitioning to its new identity. He is clear, a revanchist Russia today – inspired by a vision for territorial expansion/recovery of its ‘Near Abroad’ former empire – is as much a threat to itself as it is to its old ‘enemies’.

Third, mindful of the massing of troops on the Ukrainian border and bolstering of Belarus, Kazachkov is a robust critic of Putin and of all who devalue democracy and freedom. Though open-eyed about the crisis of Western identity, Kazachkov is also clear about the timing of Putin’s aggression: it shakes a weakened West and covers Russia’s socio-economic decline, with a staggering 20-30% of the population in profound poverty. Willful disunity among the members of the ‘Western Alliance’, who share a basic commitment to peace and justice, is to Kazachkov as reprehensible as the blatant oppression of totalitarian regimes worldwide. He makes a good point! Time will tell whether a weakened Western leadership will defend historic allies in the Baltics and elsewhere.

So, is the fall of the Soviet Union worth celebrating 30 years on? And what lessons can be learned from the intervening period? To Kazachkov, these aren’t easy questions to answer. His ‘third life’s work’ offers, I suggest, some valuable pointers, albeit more provisional and theoretical than some might want. Let me highlight four by way of conclusion.

First, Kazachkov is still committed to the principle of ‘deterrence’; that is, protecting peace by appearing to prepare for war. ‘Deterrence theory’ gained traction during the ‘Cold War’ as Western powers sought to instill doubt and fear in Communist minds. But, as Putin knows well, ‘deterrence’ only works for so long, and carries a built-in caution to the deterrer, ‘Consider how you would fair if your attempts to deter nuclear powers failed.’ One key lesson from this – as illustrated by the aftermath of Christmas 1991 – is diplomacy needs energy, flexibility and creativity. To Kazachkov, Western diplomacy was weary, weak, and dull after the collapse of the Soviet Union; and this in contrast to the energy the West (especially Germany) poured into German reunification and rejuvenation of Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall two years earlier. The advice Kazachkov and others gave was, it seems, ignored: financial bailouts – that preferred strategy of tired, unimaginative diplomacy – would render Russian reform less urgent. The window of opportunity closed quickly. Today a modern, but essentially unreformed, Russia has recovered its taste for authoritarian leadership while millions of impoverished citizens struggle to survive. ‘Deterrence’ holds Russia’s leaders’ feet to the fire when its citizens cannot. The failed Western diplomacy of 30 years ago is worth recalling as a cautionary tale of missed opportunities.

Next, play by the rules, but keep your cards close to your chest. Looking back, as Gorbachev’s misleading of the UN revealed, enemies of the West may not play by its rules. Kazachkov is clear: ‘You can’t deal with a serial violator of treaties by signing new treaties.’ He cites an agreement floated recently by the Russian Foreign Minister that would define what former Soviet states must or must not do viz-à-viz NATO and Russia. To Kazachkov, ‘Dealing with bullies on the playground will not protect you, and like most bullies, Putin is likely seeking advantage through a bluff.’ In other words, act smart and tough. To go after the Western bank accounts of oligarchs, say, to squeeze the system where it hurts, rather than to impose more economic sanctions (that Putin can denounce as anti-Russian aggression) or to match the build-up of troops on the borders Ukraine (where Russia is already primed for a fight) with NATO activity in Poland and/or the Baltic states. ‘Be creative!’, Kazachkov counsels, ‘and don’t let them know what you are up to!’

Third, using Reagan’s playbook, work to cultivate respect and support from the Russian people, and don’t overlook anything that might challenge Putin’s standing inside Russia. If possible, allow a confusion of national boundaries to inspire your creativity, as much as it does Putin’s global activity. As an example of this – and of Kazachkov’s creativity – he has proposed turning post-Soviet and US laws against the Putin regime. According to the former, he points out, compensation can be claimed by current and former Soviet citizens for property confiscated (during seven decades of Communist rule) as punishment under Soviet law. Thousands could claim compensation … legally. Imagine the chaos and cost this would cause, Kazachkov argues, to say nothing of the thanks this might attract from even the most ardent of Putin supporters. And, if courts controlled by Putin denied justice, why not press for a hearing in the European Court for Human Rights and with American lawyers and courts (with precedent found in the Alien Torts Act of 1789) assisting their claims, supported perhaps by a resolution in Congress to enable a class action by victims of Soviet terror? To a mind attuned to the potential of dual national identity such strategies are second nature!

Last, recognize the abiding power of historic Western values. Despised maybe at home, it is good to be reminded by a man like Kazachkov that the success of Christendom lay in no small measure in its superior civilizational values. ‘Trust them again’, he would say. ‘Operationalize them in your engagement with hostile powers, such as Russia today.’ The values that inspired Congressmen Wolf and Smith to seek the release of ‘prisoners of conscience’ in Perm 35 were far from weak or ineffective. In terms Kazachkov has employed, ‘tactical injections’ into the Russian social fabric can still act as a dynamic ‘nucleate’ to concentrate socio-political ‘good’. Offer generous aid packages to feed Russia’s starving, provided its distribution is handled by the opposition lawyer Aleksey Navalny’s (b. 1976) Foundation Against Corruption; engage in a proactive PR campaign to expose the deficiencies (again) of an ideologically oppressive Russian state. As Kazachkov says, ‘Without tactical injections the nucleates are simply too small and immature to effectively compete against the entrenched pyramids’ of the Russian state system. And again, ‘It is not enough to merely punish Moscow for its hostile acts. The time has come to start worrying about our image and projecting our values in post-Putin Russia.’ To Kazachkov, the events of Christmas 1991 are worth recalling because, ‘Russian internal developments are [once again] reaching a critical point.’ The build-up of troops on the Ukrainian border may confirm his worst fears.

I end with a story Kazachkov tells to encourage Western leaders not to lose heart but to take the fight to Moscow’s door. We are back in the Gulag. The Former KGB Chief Yuri Andropov (1914-1984) has just become the Kremlin master. Kazachkov writes:

Their day had come. So, a KGB VIP from Moscow came to the prison to talk to me and said, ‘You’re a reasonable man. You could hope to overcome, to achieve something before. But now that Andropov is in the Kremlin, it makes no sense. Why don’t you simply give in, and we’ll set you free – probably even allow you to emigrate. What’s the issue?’

So, I said, ‘Tell me what makes you so afraid? What’s up? You know perfectly well that when the time comes for you to face a court of law, if it’s us, the dissidents, who will be conducting your trial, we won’t seek vengeance. Conditions in your prison will be quite different. There won’t be any starvation diets or freezing cold, and you’ll be free to communicate with your families. You’ll be kept in prison only as long as you’re a threat to society. After that, you’ll be pardoned and set free. No big deal. So, what’s up?’

He didn’t deny a word I said. Pretty astonishing. Instead, he said to me, ‘Oh, I know if people like you put us on trial, everything will be just like you say. But you will never have a chance to get us into the courtroom. The people will shred us to pieces in the streets first.’

The day of reckoning for the KGB and its enablers never came 30 years ago. Celebrating the fall of Putin’s Russia may be premature. What this story illustrates is still sound: evil fears, and so can be ‘deterred’, while courage of Kazachkov’s type awakens other virtues.

Randy Tift, Senior Associate