I am delighted my brother Jonathan and I have been able to collaborate on this week’s Briefing. Jonathan was educated at Highgate School in London, and then at Oxford and Harvard Universities. He was in the education profession for 42 years and served as Head of two American independent schools for 34 years. He continued to teach classes throughout. He is now an independent school Trustee.

I have been asked to reflect on the character, content, and global impact of US education.[1] The Spanish missionary priest and teacher Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), founder of the Jesuits, famously said, ‘Give me a child till he is seven years old, and I will show you the man.’ He was right in seeing education as foundational to life. He was wrong to suggest formation stops at seven … and only boys can, or should, be educated! I was schooled in England and have taught in American schools for almost fifty years. I have often pondered the strengths and weaknesses of the two systems, mindful there are passionate advocates, critics, and beneficiaries of both around the world. It used to be assumed the young gentlemen who attended my kind of (private) school in the UK would become captains of industry, hold high office, or serve the Crown in some far-flung corner of the Empire. Sport taught resolve, hierarchy responsibility. Now, I fear, a majority in my old school have less exalted aims, their gaze fixed on their first Porsche, a fat investment portfolio, enviable holidays, and early retirement. Loyola would be disappointed! But his vision to project and instill values captures the essence of education. We are right to ask what values shape education today, andwhat kinds of people does American education presently produce?

I can’t say much in this short Briefing. While living in the US, it has been my privilege to attend Harvard for further education, to teach and run excellent schools in the mid-West, and to reflect with teachers, Heads and Boards across the US on the character and quality of their work. I draw on a lifetime of teaching and, I should stress, learning. Sadly, I can’t begin to convey the energy, spontaneity, and pleasure I’ve known in schoolrooms when society outside seemingly struggles to believe, ‘The best is yet to be’.

Three caveats before I begin. First, this is a necessarily superficial overview of a vast, evolving subject. Getting education right matters and matters more than troublemakers and educational tinkerers seem to believe. Second. I haven’t time to compare US education with other countries. So, I don’t answer an ‘Oh, we do that here, too’, or ‘That wouldn’t work here because…’. Comparisons can be useful: they can also compromise focus. Third, education is political. Preparing young Americans for life in a divided country and rapidly changing, conflicted world is hard. People have opinions, in a democracy a vote. The design, implementation, and long-term implications of American educational principles, mandates and expectations, are now profoundly political. They spew from and into ‘hot topics’ of personal freedom and faith, of ‘identity’ and social history. As never before, perhaps, curricula are the battleground for new ideas, agendas, and socio-political ideologies. Teachers and pupils are pressured by political shibboleths to suppress private opinion/s. With American education (as in many countries) predicated on provision from pre-school to college (and beyond) in public and private institutions, the breadth, depth, and complexity of the issues raised, are immense. Add to that (some) absorption of international educational ideas and the legal responsibility of states and school boards to set standards and shape expectations, and you have a veritable Atlantic of stormy issues. What follows are mere snapshots, vignettes, anecdotes, and broad-brush strokes on contemporary ‘American education’. At this stage in life, I am glad (and sometimes sad) to sit back and watch. As the sage Confucius (551-479 BCE) advised, ‘Acquire new knowledge whilst thinking over the old, and you may become a teacher of others.’

Elementary School

Since ‘Early Childhood’ or ‘Pre-School’ offerings are (surprisingly, perhaps) not universal in the US, I begin with Elementary Schools. In 2021, there were 87,498 schools covering grades K through 8 in the US of which 67,408 were state registered.[2] The Lower levels of Elementary schools teach from kindergarten[3] to 4th or 5th grade (10- to 12-year-old) in self-contained classrooms.[4] A teacher is responsible for math and language arts skills (viz. reading and writing). These are the basics. As retired US Senator Lamar Alexander (b. 1940) described public education, ‘to teach reading, writing, arithmetic and what it means to be an American citizen’. But the degree to which this vision prepares pupils for 21st America and global citizenship is discretionary … and thus patchy.

Through standardized tests (required in many states for state-supported schools) students first encounter science (i.e., the laws of nature and basic principles of physics) and social studies (viz. how society functions at a local, federal, and national level). They also learn of key dates, prominent national figures, and some (mostly US) current affairs. Many schools, especially in the private/independent sector, supplement this with ‘specials’ such as ‘Arts’ and PE. Technology, as a stand-alone or connected subject, is also commonplace. But, and here we encounter a potential weakness in early years American public education, foreign languages are rarely taught in public schools (unless a school district decides otherwise[5]), whereas they have a prominent place in private/independent school curricula, on the basis that early learning of another language is easier short term and valuable long term.

Language learning is rarely linked to Geography. Elementary pupils may learn about local, state, and national geography, but this is limited to landmarks and major physical features. Few schools in the public or private sectors expand Geography into human behavior and decision making, let alone into culture, conflict, migration and ecology. For quite different (constitutional) reasons, religion – including ‘comparative religion’ and the role of religion in history and contemporary geopolitics – is not taught in public schools. Most non-public schools are faith-based and teach religion freely; albeit their religious affiliation may influence their instruction, with ‘faith’ as a diverse, global phenomenon downplayed. Outside the official language and rituals of religion, millions of Elementary School students recite the ‘Pledge of Allegiance’ regularly, and sing the ‘Star Spangled Banner’, ‘America the Beautiful’, and ‘My Country ‘tis of Thee’ often and from memory. In short, Elementary education prioritizes American ideas and ideals past and present. Patriotism is nurtured.

Middle School

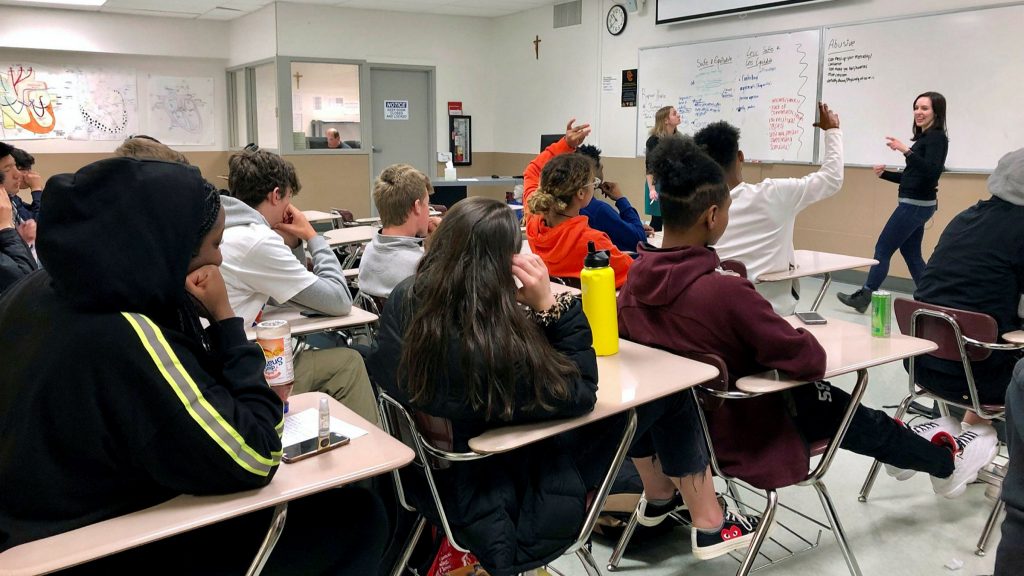

In 2019, public schools in the US educated 50.8m. children. Of these, 23.7m. (46.6%) were white, 13.9m. Hispanic, 7.7m. Black, 2.7m. Asian, 0.5m. American Indian and Alaskan Native and 0.2m. Pacific Islanders.[6] The scale and diversity of this educational pool is a reminder of the breadth and depth of the challenge American educationalists face. With over 18m. children in the US born outside the country (or with one parent who was), reaching across cultural divides poses problems of historic proportions. And, as education professor Dr Gabriella Oliveira stressed in a recent New York Times article,[7] to many migrants ‘American schools promise their children the opportunity for a better life.’ Widely reported violence in America’s schools is a grotesque reminder that social needs, tensions, ideas, and ills infect classrooms, study halls and corridors. American teachers and pupils are affected; not least in ‘Middle Schools’, for grades 5 or 6 through 8 (11–13-year-olds).

There are a reported 13,477 Middle Schools in the US. In broad terms, both the context and focus of the educational experience change here from a self-contained classroom with one teacher to instruction by specialist teachers in different settings. Stability and foundation laying give way to mobility and growth. A homeroom teacher may still lead in a couple of subjects – and additional teaching in the fine arts and physical education often occur – but specialist teachers now cover the major disciplines to prepare pupils for later studies. More public Middle Schools now offer foreign languages, and in both public and private settings instruction covers a language and its associated culture. Spanish and French are still widely taught, German less so Mandarin increasingly.

Induction in life outside the town, city and local community will vary from school to school, although in my experience most Middle Schools teach more about local values than global responsibility. Classes in Social Studies expose students to key periods and events in history and to national social issues. In 8th grade, students habitually study US history and government, and to enhance book work take field trips to state and national monuments and places of historical significance. The aim is clear, to help students grasp the history and inner workings of the US to foreground its social, political, cultural and artistic life. The weakness of this? It marginalizes international issues or leaves them at the discretion of the teacher and school. Global awareness is patchy, a grasp of global issues limited. That said, in my experience, teachers who are passionate about another country, culture and issue are remarkably adept at conveying this to their pupils! All strength to them, I say.

Perhaps the greatest threats to Middle School education come from parents and society. The life of an American adolescent is, to quote the famous Victorian duo W.S. Gilbert (1836-1911) and Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900), ‘not an easy one’. Friendship, family and finding a safe place to ‘be oneself’, pose immense challenges. Understanding this, a Middle School can provide security, vision, hope and community. Peer pressure and social mobility threaten this. It is as common, in my experience, to see a Middle School student lose his or her identity as find it. Yes, life demands that they face reality and make decisions, but Middle School pupils need special care at this formative stage in life. The pandemic hit them hard, their concentration and aspiration compromised by disruption and isolation. Wise mentors of Middle School children watch for depression.

High School

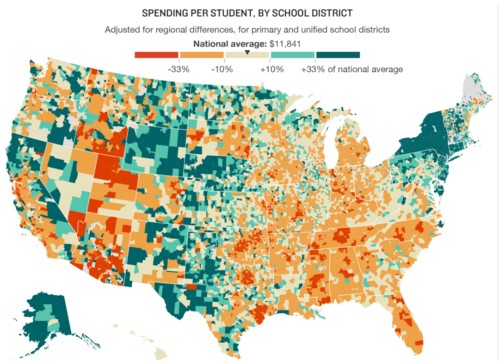

According to NCES, public schools in America have on average 526 students, classes of 24, and a pupil ratio of 16:1. In 2019-2020, the budget for each pupil in public elementary and secondary schools was $13,440, with national expenditure $680bn. The education of America’s children does not come cheap, especially if you add what wealthier parents and schools invest for high grades and entry into premier colleges. Is it good value for money? Do America’s young learn what and how they should? These are questions educationalists, politicians, parents, and punters are right to debate. If the foundation is laid in Elementary and Middle schools, the superstructure is constructed in High School and college. Here pressures grow, choices are made, new challenges emerge, and dreams are born. As Hollywood discovered decades ago, to many parents, teachers and pupils, the best and worst of life are found in an American High School. As one commentator put it:

For some, high school is the peak of their life: You’ve got prom and pep rallies, and homecoming and hormones. For others, it’s the pits because you’ve got … well, prom and pep rallies, and homecoming and hormones. And there to capture every awesome/awful moment are these high school movies which earned high grades from film critics.[8]

From The Last Picture Show (1971) to American Graffiti (1973), Dead Poets Society (1989) to American Pie (1999), Freedom Writers (2007) to The Duff (2015), and countless teen movies US filmmakers have produced in the last fifty years, High School years have been profiled and praised, ridiculed and ransacked, to make money, careers, a cultural point and a socio-political protest. It is no surprise ‘identity’ is now a major issue for America’s youth.

High School in the US, from Grades 9 to 12 (14- to 18-year-olds), spans adolescence. Years that are biologically and socially transformative can be triumphant and traumatic in equal measure. As in Middle School, High School education centers on the ‘five basic’ classes, viz. English/Language Arts, Math, Science, Social Studies and possibly a Foreign Language (N.B. less than 50% of states require a student take a foreign language class before Graduation). These five courses are again supplemented by fine arts and physical education. Where a foreign language is taught, it builds on Middle School programs, likewise world history and particularly US history. Students aren’t required to take all the ‘five basics’ in High School. In many cases, ‘electives’ fill gaps. In terms of a student’s preparation for life in society and in the wider world, many states require a semester on the US Government, and schools often encourage student electives in Economics (micro and macro), Speech and Debate. The breadth of topics is determined both by the school and faculty, and by parental pressure. Electives are not subject to the same expectations and examinations as the ‘five basics’. They become the seedbed of new interests and ideas about the future.

Even in High School, ‘Geography’ is rare. In recent studies, Social Studies teachers devote less than 10% of class time to Geography and geographical (and geopolitical) literacy. National tests show 80% of Middle and High School pupils ‘below proficient’ in this area. The impact on a student’s self-awareness and sense of connection to a globalized world is too rarely recognized. America’s place and profile on the world stage are threatened by the myopia of educational parochialism. 21st century students deserve better.

Outside class opportunities abound for High School students to develop new skills. Debate competitions, in-depth study of Congress and the Constitution, and a program like ‘Model United Nations’, are excellent ways to teach students about communication and persuasion, lawmaking and diplomacy. Lawyers and politicians, media moguls and actors, discover their vocation here. Over the years, media giants have made millions out of American High Schools.

College

My focus in this Briefing has been pre-college education in the US. For a host of complex personal, socio-economic and professional reasons, fewer and fewer High School graduates proceed to postsecondary education. The statistics are revealing. In the Fall of 2020, 15.85m. students enrolled in colleges across the US. This represented a year-on-year (YoY) decline of 4.31%. In the same year, the total number in postsecondary education fell 3.29%, the steepest decline since 1951. Early data from the Spring of 2022 indicates total postsecondary education had fallen yet further to 16.2m, viz. a YoY decline of 14.7%. Contrast this with a 455.9% increase in Hispanic students since 1976 and a doubling (or 98.1%) of females in college since 1947. It must be acknowledged that much of the decline in college enrolment numbers has been attributed to the effects of the pandemic, with students being asked or choosing to attend classes remotely, and many finding the expense of such virtual learning not worth the product. Nevertheless, what is true of schools is true of colleges: they reflect changes for good and bad in society at large. Some catch a vision and seek to succeed, some fall too soon through the net of life. ‘Life-long learning’ is in many parts of the world inseparable from the ‘American Dream’; for some it remains a dream, for the lazy a terrifying nightmare!

It is at college American students encounter the greatest opportunities and encouragement to expand their ideas, education and horizon. ‘Study abroad’ programs offer many their first chance to ‘see the world’, while large numbers of international students come to study in American undergraduate and graduate programs. The world begins to shrink at college. The fact, responsibility, and rapidly changing reality of America’s global profile, become more immediate. For the first time, life and beliefs in another country and culture become intriguing, enriching and potentially troubling realities. A collegiate ‘dialogue of cultures’ illuminates America’s ‘culture wars’. Of course, there is always more to learn, but for many American students, college reshapes their worldview and broadens a narrow horizon. For some, this will lead to life and work ‘overseas’, to others a partner raised in another culture, to others the pleasure and potential of life-long learning through travel. Schools begin the journey which colleges continue. In the end, a pupil decides where they both lead. To quote Confucius again, ‘By three methods we may learn wisdom: first, by reflection, which is noblest; second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience, which is the bitterest.’ Life is not all school or college claim it to be. Chance and choice have an uncanny knack of re-writing our story.

Three final points

During my life and work in America, three ‘paradigm shifts’ have reshaped education. I list them here hoping policymakers, parents and educators will take note.

First, the move from (what some call) ‘essentialism’ to ‘experientialism’; that is, from objective content to personal preference. In education, an ‘essential’, objective core curriculum (where students are taught what professionals decide) has been challenged by more open-ended exposure to subjective ‘experience’ (with students now left to rely on their own limited perspective on life). American culture has led the world in this reorientation of knowledge from a life journey of discovery into the factually ‘unknown’, to inward, subjective exploration of what a person has always inarticulately ‘known’. In the former lie ‘fact’, ‘truth’ ‘knowledge’ and ‘sense’, in the latter ‘impression’, ‘perspective’, ‘preference’ and ‘feeling’. At the same time, a managed shift from ‘fact’ to ‘application’ has pedagogical merit, and the hijacking of classrooms by ideology is both disruptive and disrespectful. Are students not free to find, write, dig and believe? The harsh – and too often oppressively depressing – reality for America’s teachers is that academics and educational practitioners are increasingly attacked and constrained by politicians and talk show hosts who put their own self-interest above the education and welfare of young people.

Second, the paradigm shift from ‘book’ to ‘internet’, viz. from a circumscribed and finite mountain of knowledge to an infinite galaxy of fragile and fragmentary data. The former offers the hope of ascent, the latter the threat of alienation. A student born into and resourced by the internet faces a different educational challenge from those of us who were assigned respected texts and commentaries. Technology offers new ways to learn, with the teacher more an interpreter than imparter of knowledge. But I don’t envy the young. A galaxy of knowledge is intimidating. Sound guides and responsible oversight are vital if the quagmire of internet knowledge and intrusive social media is to be traversed. Students learn more today outside the classroom than at any point in history. Limited and distorted news and abusive social media pervert and distort knowledge and ruin life.

Lastly, the shift from ‘Empire’ to ‘Partnership’, viz. from an accepted level of American cultural, political, and economic ‘colonialism’ to a new, confident, post-colonial vision of a global partnership among grown-up nations. This is not to question the patriotism evident in American schools, but it is to recognize that globalized youth culture sits ill with claims for geopolitical ascendancy. Astute educators (like Confucius and Loyola) have always found ways of instilling transcendent ‘virtues’ while nurturing local ‘values’. They are much needed today. After all, what is the point of promoting and pursuing an ‘American education’ if it fails to bring peace to a troubled world. Thankfully, youth counterculture is increasingly ready to indict systems adjudged ‘unfit for purpose’ and try something new.

Jonathan Hancock – Guest author

[1] The 2022 American Education Week was from 13-19 November.

[2] N.B. in the same year, 69.4% (ca. 35.1m.) of all Kindergarten-12th grade pupils attended public (viz. non-private or independent) schools. In 2019, 7% of all public schools were ‘Charter’ schools. Charter schools appeared first in Minnesota in the early 1990s, their aim being to improve public school education. By 2017-2018 there were 7,193 charter schools across the US attended by 3.1m. pupils. California recorded the highest number of charter schools (1,268), the District of Columbia the highest percentage of students attending them (44.8%).

[3] N.B. not all states require or fund Kindergartens.

[4] According to NCES (the National Center for Education Statistics), in May 2022 there were 130,930 K-12 schools in the U.S. In 2019-2020, NCES recorded 70,039 public and 18,870 private prekindergarten, elementary, and middle schools (N.B. down from 70,142 and 21,611 respectively in 2009-10). Economics, social mobility and demography necessarily affect the quantity and quality of education across the US and her dependent territories.

[5] There are 16,800 school districts in the US, the largest of which is in New York City with currently 984,462 students.

[6] Cf. www. https://research.com/education/american-school-statistics; accessed 9 December 2022.

[7] Cf. Gabriella Oliveira, ‘School is for Hope’ (New York Times, 1 September 2022): https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/01/opinion/us-school-immigrant-children.html; accessed 9 December 2022.

[8] Cf. https://editorial.rottentomatoes.com/guide/best-high-school-movies; accessed 9 December 2022.