A few years ago, I sat with a dozen or so (far more) eminent experts in a secure UK location and reflected on ‘Future Trends’ that Britain faced. Knighted scholars and Generals, anthropologists and economists, security analysts and diplomats considered the findings and conclusions of 120 scholars. I was there as a lowly representative of ‘religious and cultural’ trends that potentially impacted Britain’s identity, security, and economic flourishing. When called on to provide an overview of cultural, ethical and religious issues the UK faced, to the palpable shock of most of the others sitting around the table, I began by opening a Bible and reading Psalm 24: ‘The earth is the Lord’s and everything in it, the world and all who live in it …’

When I finished there was a rather embarrassed silence – which I didn’t attempt initially to fill – but then I added, ‘It is vital we remember a majority in our world “read life” through some kind of religious text.’ They got the point. The discussion flowed on into tea and dinner. Honest – very honest and personal – confessions of agnostics and atheists, who were gracious enough to admit that, though they didn’t ‘get’ or always respect religion (certainly not in a formal or institutional form), they saw a ‘trend’ towards what scholars might call ‘conscientized spirituality’ in a post-secular world.

That was all before ISIS, President Trump’s relocating of the US Embassy in Israel and COVID-19. As I chided a ‘Town Hall’ meeting of the faculty of Oxford University’s prestigious Department of Politics and International Relations, when they attempted to justify exclusion of religion from their deliberately – and, I found, passionately! – secular courses, ‘Which world do you live in?’ There was a certain amount of silence then, too! They were sure they ‘read’ the world aright.

We all ‘read life’, consciously or unconsciously, through our backgrounds, politics, prejudices, media preferences and personalities. Despite our protestations of being ‘unprejudiced’ or ‘tolerant’, none of us is tabula rasa.

‘Textualism’, as it is called (viz. the reading of life through some kind of ‘lens’), isn’t restricted to people of faith. The deliberate ‘secularizing’ of scholarship, diplomacy, and perception, that has dominated Western culture since the 18th-century Enlightenment, is only one expression of this phenomenon. We all ‘read life’, consciously or unconsciously, through our backgrounds, politics, prejudices, media preferences and personalities. Despite our protestations of being ‘unprejudiced’ or ‘tolerant’, none of us is tabula rasa. Psychologists teach us we cannot be. We need mental ‘schema’ to interpret data. So, I ‘see’ what I have consciously and unconsciously learned, or chosen, to see. I ‘read’ the world through a ‘lens’. The difference between people of faith and others is that the colours in their ‘lens’ include the hues of transcendence and ethics, tradition and accountability, self-sacrifice, and eternity. It is when our ‘lens’ is darkened by the grime of assumption and privilege, projection, and pride, we see little, if anything, very clearly.

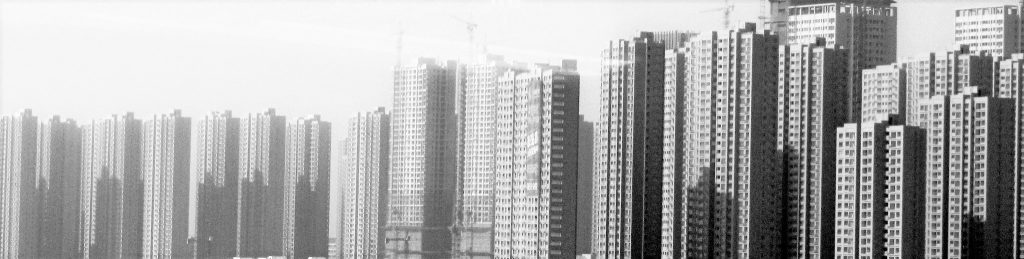

As someone who has visited China numerous times, taught in many of her leading universities, and count many Chinese dear friends, I have often grieved at the distorting ‘lens’ of Western media coverage, of inept diplomacy and, thence, of popular perception. None of these in any way reflecting the China I know well and still love; indeed, it is because of these that I grieve again at the ‘Second Cultural Revolution’ that now grips the country under President Xi Jinping.

‘Reading’ China is notoriously hard. Many a time I have scratched my head at the seeming impossibility of ‘bottoming things out’. Layer upon layer of courtesy, bureaucracy and power veiling agendas shrouded by Mandarin or gripped by patriotism and pragmatism. It isn’t easy. Of course, China isn’t unique. Every culture and language is to some degree opaque. But China does love to be ‘exceptionally’ hard to read. It hides behind the bamboo curtain of language. It apes and mimics Western behaviour (good and bad) to cover its own. It plays feints, and side-steps direct questions and conclusions, to keep others guessing. Those who know the country and culture well sigh when we see such mischief making … and time after time! Alas, those less well acquainted with this vast, ancient country (albeit morphed into its fluid, new socio-political and imperialist identity) misread it over-and-over again. We fall for China’s deceptions. We take its actions at face value. We misconstrue its intentions. We draw wrong conclusions. And China is having a ball! The ‘lens’ over eyes prevents us ‘reading’ it aright. What could be better…

Oxford House’s primary vocation is to ensure the cultural, ethical, and religious dimension is fully and accurately integrated in analysis of and engagement with contemporary geopolitics.

Oxford House’s primary vocation is to ensure the cultural, ethical, and religious dimension is fully and accurately integrated in analysis of and engagement with contemporary geopolitics. There is much under this heading that applies to our on-going work on China. Let me suggest three issues that we are sensitive to – and concerned about – at the moment:

- China’s policy of ‘sinicization’ or ‘sinification’; that is, the imposition by the government of a centralized perception of Chinese language, identity, culture, and history. This is ideological totalitarianism by any other name. Of course, China, as an independent sovereign nation, is free to make such decisions, and at one level outsiders have no business voicing an opinion on those decisions or trying to reverse them. However, China’s trading partners, and (often most feared) near neighbours, are also free to decide China is not the country it was when bi-partisan trade deals were agreed. Yes, countries and cultures change, but rarely in isolation. ‘Reading’ China involves the world asking, ‘Are we going to buy what they want – and urgently need – to sell?’

- China’s rigorous policing of religious activity. One of the things that the Chinese leadership has struggled to understand – even during the heady liberalizing days of Deng Xiaoping – is that global religions are precisely that: global. They think and act globally. They find commonalities and affinities across continents. This isn’t the result of a subversive attempt to rule the world: it is a natural expression of their spiritual and religious identity. A Christian in China is a Christian: that is a principle the ideology of ‘sinicization’ or ‘sinification’ cannot accept. To the Chinese, a Chinese Christian must be a Chinese Christian, just as a Uighur must be a Chinese Muslim. But let’s be very clear, we outsiders have made it harder for people of faith in China, when culture and politics have perverted faith and perception: so we become British, Korean, and American Christians (or any number of other forms of culturally determined religious ideologue). Here again, I fear, China has simply mimicked our behaviour. Are we ‘buying what they are selling’ about the relation between religion, culture, politics, and society? I certainly hope not!

- China’s de-humanizing communistic militarism. Analysts are probably right to ‘read’ China’s crackdown on the Uighurs in Xinjiang, its threatening military build-up on the straits of Taiwan, and its callous imposition of new laws on Hong Kong, as a smoke screen to cover the economic crisis COVID has compounded and the resultant weakening of the central government’s power. How do you deceive an enemy when you are running out of bullets? Use echoes to maximum effect. Huawei can help with this. China is most bullish when most vulnerable. Control covers fear. The strong don’t need to be defensive and aggressive. But there is a darker side to this hackneyed Chinese behaviour. In its desperation to control dissent and project strength China has revealed the ugly face of its Marxist anthropology; that people are not humans with a soul, they are units of labour without power or rights. Organ harvesting (rampant now in China) is not then immoral. When I contemplate the (implausible) reality and nature of a Chinese global Empire – which Chinese habitually hold to be their sovereign destiny and absolute right – I find myself asking, ‘What does China want? What would it do with imperial power if it obtained it?’ In answer to both, I simply don’t know – but I do know their attitude to a person – as we have come to know and admire human identity in so many other parts of the world – would be very different – horrifyingly so.

Do we really want ‘what China’s selling’? I think not. Which world do you, or would you, live in?