(Photo: Adnilton Farias/VPR)

In the history of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), Xi Jinping (b. 1953) is the first paramount leader on record to give prominence to religion in word and policy. In a watershed speech given in May 2016, President Xi called for the ‘sinicization’ of religion in China led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to ‘guide that adaptation of religions to China’s socialist society.’ This was followed up in 2018 by the National People’s Congress and the Chinese Peoples’ Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) that approved the bureaucratic, ideological, and legal structures of ‘sinicization’ that subsequently came into force on 1 February 2020.

The term ‘religious sinicization’ (宗教中国化 zong jiao zhong guo hua) most often refers to the indigenisation of religious faith, practice, and ritual in Chinese culture and society. For President Xi, ‘religious sinicization’ is primarily political and ideological. As government policy, it puts in place three CCP priorities for the monitoring and management of religion in China. Bureaucratically, it streamlines government oversight of religion. Ideologically it seeks to revive the sway of Party ideology over religious belief and practice. Legally, it provides the juridical framework to monitor and control the growth of religion and its influence in China.

(By ZhengZhou – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Administratively, the United Front Work Department (UFWD) is now responsible to monitor and control all official religious activity in China. This bureaucratic realignment allows the UFWD to ‘localize’ religion. Accordingly, the religious policy of the central government is enforced by the UFWD nationally and locally. This streamlines the monitoring and control of religion even as it allows the UFWD to short-circuit any international institutional or financial ties to foreign entities. It replaces the cumbersome, confusing and overlapping bureaucratic agencies once tasked with monitoring and regulating religion in China. Thus, for Protestant Christianity, the former muddle of multiple government and quasi-government agencies such as the China Christian Council, the Three-Self Patriotic Association, Religious Affairs Bureau, and the State Administration of Religious Affairs have relinquished their former administrative powers which are now consolidated in the UFWD.

Ideologically, ‘sinicization’ of religion addresses a ‘contradiction’ bedevilling the CCP. The rise of religious interest, practice, and identity in China have paralleled the nation’s staggering economic development and rise in international influence. Certainly, China’s growing wealth, power, and international influence are welcomed by the CCP, but the growth of religion disturbs officials and scholars loyal to the CCP and its continued reign in China. They point to research that ties the implosion of the Soviet Empire to ‘colour revolutions’ instigated by foreign agents through institutions and individuals in religious vestments. Thus, for the CCP, the rise of religion and especially ‘foreign’ religions such as Christianity and Islam represent an existential threat to the ideological health of the nation and ‘sinicization’ its fitting remedy. Thus, ‘religious sinicization’ requires patriotic education and public displays of loyalty to the CCP in churches, mosques, and temples. In officially registered churches replacing paintings of Jesus with portraits of a benevolent ‘Uncle Xi’ signal to the faithful that worship of the State, the Party and its Premier are now required. Leading seminaries in China have been instructed to provide new translations of the Bible with the removal or revision of verses or doctrines that might appear to challenge the ultimate hegemony of the CCP and are part and parcel of the lengths the Party is willing to go to bring the burgeoning Christian churches in China to heel.

These bureaucratic and ideological policies put in place by the CPPCC to rein in religion are now backed up by force of law and being felt by religious leaders and their institutions both in and beyond China. Like the purges and incarceration of suspected political enemies in the 1950’s, ‘sinicization’ lies at the root of the mass incarcerations of Muslim Uighurs, Hui, and Kazakhs in Xinjiang re-education camps, as well as the detaining and re-education of Chinese Christian pastors. This combined with the unleashing of the UFWD shows the lengths Xi and the CCP will go to enforce its ideological authority and to purge religious organisations of their international associations.

Will it work?

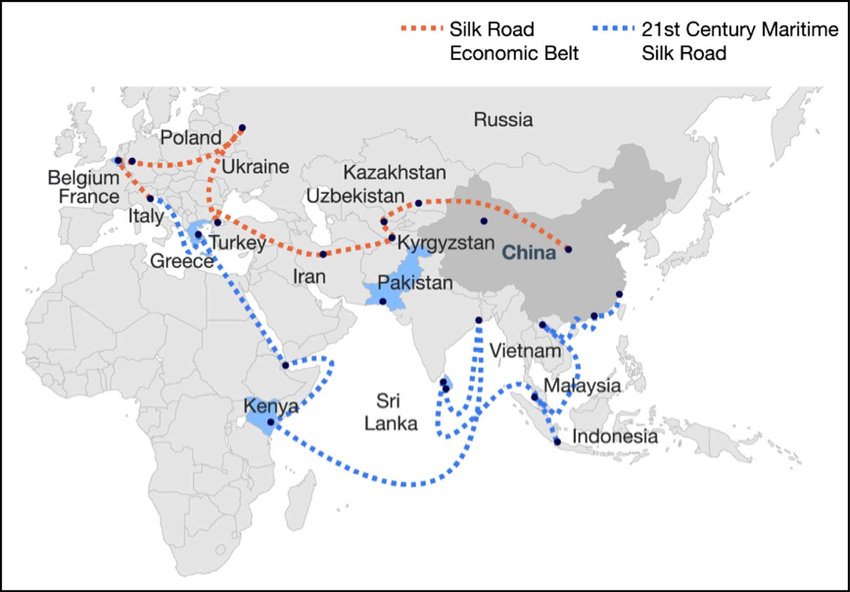

This attempt by the CCP to rein in the growth and influence of religion and religious institutions in society carries risk for Xi and the Party. China today is very different from China of the 1950’s. Then, the limitations of print media, an imposed ‘Bamboo Curtain’ permitting only a handful of officials to travel outside China, and the exuberant embrace of CCP ‘Liberation’ by the great majority of Chinese made stifling religious influence and enforcing ideological conformity relatively straight-forward. Today, however, China’s international public and private ties are legion and necessary for China’s continued economic strength and growth. The attempt to assimilate the religious affections of an increasingly educated, technocratic and connected religious adherents, risks dampening the very communications, international connections and entrepreneurial initiative necessary to drive China’s economic engine. Further, the mass incarceration of Kazakh and Uighur Muslims may have raised only muted criticism from Muslim political leaders, it has damaged China’s international prestige even as President Xi’s ‘One Belt Road Initiative’ gains traction. In time, the ‘sinicization’ of Islam could prove a serious speed bump to China’s ambitions, especially in Central Asian countries with large Muslim populations.

Certainly, China’s use of state-of-the-art surveillance technology makes it easier for the UFWD and the Public Security Agency to monitor and crush religious non-conformity. Facial recognition software in tandem with ubiquitous video monitoring even within homes allow the security services to identify and track an individual’s movement and note with whom they associate. Covid 19 has furthered the harvesting of biometric data, smartphone scanners, contact tracing, voice analysis, and satellite-tracking systems for vehicles that allow for surveillance round the clock. 5G technology only enhances the ability to monitor all aspects of lived reality. In the past, un-registered churches had been able to disappear into the massive urban-scape of China’s cities or in clandestine house groups. With the new technology the ability to ‘hide’ is greatly diminished and with it the ability to evade the effects of ‘sinicization’ on the Church and Christian mission.

Nonetheless, when it comes to suppressing religion, technology is a two-edged sword. The churches of China today are not the peasant churches of old. Exponential growth of Christianity in major urban centres have attracted young, educated and tech savvy church members, who, so far, have made their way in the ever-changing virtual world of the world-wide web. Thus, registered and unregistered churches have found ways to connect with churches and ministries beyond China. Even if the government were able to outpace individuals, they run the risk that the very attempt to control China’s international connections and communications with the outside world will diminish China’s international influence, economic growth, and power that it seeks to export in Asia and throughout the world. Using technology to stop technological engagement can prove counterproductive. Indeed, the use of satellite technology alerted Western news organisations to the growing archipelago of Chinese internment/re-education camps in remote areas of Xinjiang. At first the Chinese authorities denied the existence of the camps, only to argue later that they were being used to check terrorism in the region.

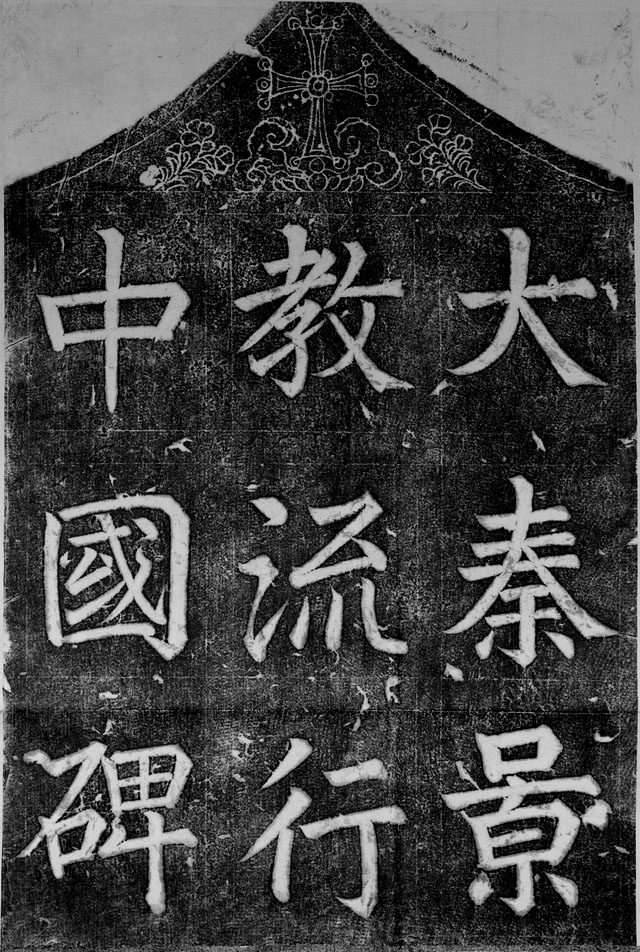

Christianity in China

Up to the reign of Xi Jinping, China had increasingly allowed the Chinese churches more autonomy allowing unregistered churches to meet openly and even question CCP rule. Xi’s policy of ‘sinicization’ is already forcing unregistered churches to revive smaller clandestine meetings to avoid the panopticon of the State. ‘Sinicization’ appears likely to be even more troublesome for officially recognised Christian churches, as China’s relatively evangelical Christians turn to unregistered churches in pursuit of orthodox Christian teaching. Given the above, the actual effect of ‘sinicization’ could well nurture the very religious autonomy that it was designed to crush. Further, given the bureaucratic demise of the TSPM and CCC, this will effectively cut off the very Chinese engagement that has served China’s official propaganda, that it guarantees freedom of religion and that its international representatives are authentic representatives of Chinese Christianity. Instead, international news outlets will turn to reports coming from Christian dissenters who will continue to make the world aware of the ongoing persecution of Christians in China.

Certainly, the current attempt to rein in religion in China will change the modus vivendi of Chinese Christian churches, but it is unlikely to cut off their continued growth and influence. Given their ability to adapt quickly, it is doubtful that the UFWD attempts at assimilation will do more than compel loyalty of the lips, but not the heart of the Chinese people.

Dr Tom Harvey, Associate