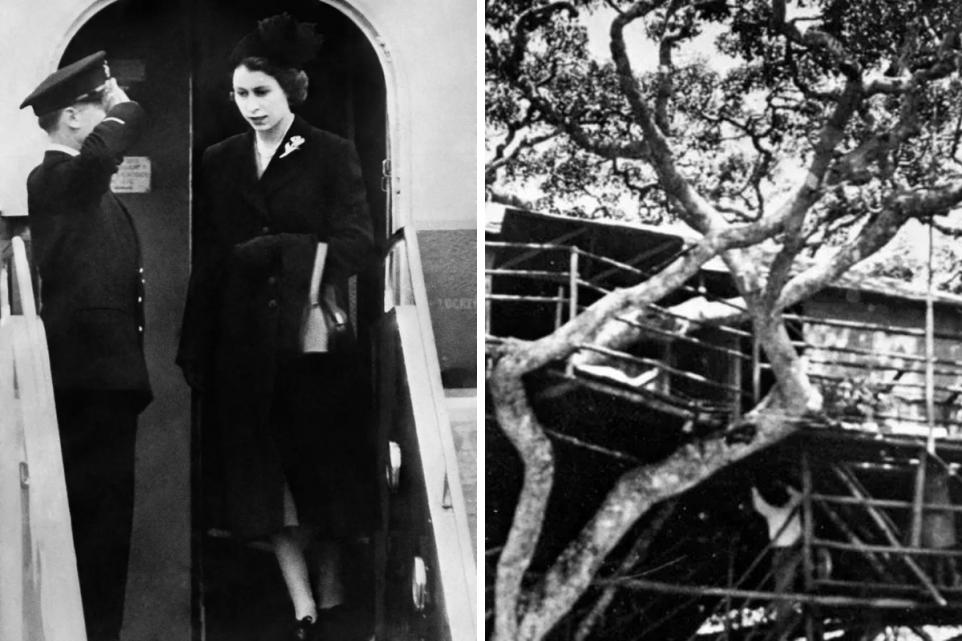

During the past few weeks, the world has witnessed two very different, but thankfully equally peaceful, transitions of power. In the young, vibrant East African country of Kenya and in the historic United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, power has, with the assent of the people, passed in an orderly fashion from one ‘Head of State’ to another in accordance with the Constitution of the two countries. Much could be said about these events in countries forever historically (and emotionally) intertwined by the announcement to young Princess Elizabeth on 6 February 1952 of her father King George VI’s (1895-1952; r. 1936-1952) death, while she was staying with her husband Prince Philip (1921-2021) in Treetops Hotel, Kenya, at the end of an early foreign tour.

In this Briefing I want to focus on the way these two transitions of power have occurred, and what light they shed on the past, present, and potential future of these two quite different systems of government, one with a directly elected executive President, the other with an unelected hereditary Monarch.[1]

Though part of the British Empire until 12 December 1963, and a constituent member of the Commonwealth thereafter, there are substantial differences between the recent transition of power in Kenya and the United Kingdom. We can learn much from both.

In Kenya, change resulted from its 4th President, Uhuru Kenyatta (b. 1961; Pres. 2013-2022), relinquishing office at the end of his second term (as mandated by the Kenyan Constitution), and the election on 9 August 2022[2] of his experienced political successor (and former 11th Deputy President, 2013-22) William [Kipchirchir Samoei Arap] Ruto (b. 1966), a member of the relatively newly formed (from December 2020) United Democratic Alliance (UDA). In the UK, the death on 8 September 2022 of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022; r. 1952-22) was followed by the formal accession of her eldest son, Prince Charles (b. 1949), as King Charles III, in accordance with historic constitutional precedent.[3] To many, though the Queen had become visibly frailer since Prince Philip’s passing on 9 April 2021, her own death at Balmoral Castle, Scotland – just two days after bidding farewell to PM Boris Johnson (b. 1964; PM 2019-2022) and inviting the new leader of the Conservative Party, Liz Truss (b. 1975; PM. September 2022 – present), to form a government – was no less unexpected than her father’s death when she was out of the country in 1952.

Drilling down into the details of these historic events in Kenya and Britain is revealing. In the case of President Ruto, the people’s assent was clear but limited. With a turnout of 64.77% Ruto secured 50.49% of the vote, while his opponent, the former Prime Minister Raila Odinga (b. 1945; PM 2008-2013) of the Azimio La Umoja party, gained 48.85%. Despite objections, the Supreme Court upheld Ruto’s election and on 13 September 2022 he was sworn in by Chief Justice Martha Koome (b. 1960; CJ 2021-present) in a ceremony attended by thousands of his supporters and more than twenty other Heads of State. Thankfully, the violence and political unrest associated with recent Kenyan elections – notably those that followed the re-election of Kenya’s 3rd President Mwai Kibaki (1931-2022; Pres. 2002-2013) in 2007, in which more than 1000 people were killed – were conspicuously absent. Why? First, because President Kenyatta adhered to the ‘two term’ limit to his office (in contrast to an increasing number of world leaders, who change the rules to perpetuate their position). Second, because Odinga did not prolong his challenge to the Supreme Court’s decision. These two factors protected Kenya’s transition of power.

But what of the people’s assent in the case of King Charles III? To some, it might seem, this has no real place or significance in a hereditary monarchy. This is not the case. The people’s assent is essential before, during and after the accession. It is embodied, first, in the actions of the Accession Council. Following tradition, this took place soon after Queen Elizabeth’s death. Composed of the Privy Council (viz. elected politicians, past and present, including former PMs), holders of senior public offices, the Lord Mayor and High Sheriffs of the City of London, and High Commissioners of the UK’s overseas realms and territories, the Accession Council (chaired by the Lord President of the Council) met first in private to agree the new monarch and then proceeded to receive the new King’s sworn oath. As historic precedent dictates, there was then a proclamation of the new Sovereign, Charles III, read by the Garter King of Arms, on a balcony outside St James’s Palace, London, in the presence of the Earl Marshall (the 18th Duke of Norfolk) and two of the Sovereign’s Sergeants-at-Arms. Similar ceremonies were then held (as they have been in recent times) in Edinburgh, Belfast and Cardiff.

On the surface, this process can seem little more than mere pageantry or a political formality, with no possibility for change or opposition. In fact, the proclamation of the new Monarch by the Accession Council (and his/her subsequent reign) is a reflection of the current ‘settled will’ of the people’s elected representatives, for whom King Charles is now Head of State. This ‘settled will’ of the people can – and, indeed, may – change one day, as it did in the former Commonwealth country of Barbados in 2021 when its elected assembly voted in a new Republican system of government. Queen Elizabeth II ceased to be its Head of State, and, with characteristic good grace, sent shortly afterwards her ‘warmest good wishes for your happiness, peace and prosperity in the future’.

A second way the people’s assent is reflected (and protected) in the British system is through polling. Polls are taken regularly by governments to assess the state of public opinion and levels of support for government policies. In a recent YouGov poll (taken on 13-14 September 2022) 67% were in favour of a monarchy, 20% of an elected Head of State. Of those who responded, 64% were against holding a referendum on monarchy, 22% were in favour. This data is significant for the running of the country. Crucially, if at any point these percentages change significantly, parliament will take note and respond accordingly. The voice (and vote) of the people can, and must, be permitted to speak … even in a monarchical system.

The third way in which the people’s assent is subsumed in British public life is in the UK’s openness to royal involvement in national events and popular charities. King Charles III became King on a wave of public support and sympathy for the royal family in their grief. The Queen’s funeral was watched by an estimated 24m. people in the UK and tens of millions worldwide. Almost 30,000 people attended the late sovereign’s ‘lying at rest’ in Edinburgh Cathedral, and more than a quarter of a million queued for hours for her ‘Lying-in-State’ (September 14-19) within the bare, ancient walls of Westminster Hall, London. The vast numbers mourning the late Queen and welcoming the new King were a visible, emotional, demonstration of public assent. Good will is of the essence of constitutional monarchical power and effective socio-political influence.

But the differences between the position of President Ruto and King Charles III remain substantial. The former is an executive President and leader of a political party, who will determine the course of the Kenyan Government for a limited period (no more than 10 years, should he be re-elected in 2027). King Charles III is a constitutional monarch, who reigns above party politics and will continue as Head of State until (he has made clear) his death. That both men became Head of State peacefully and constitutionally, and with the assent of their people, is of immense significance and benefit for their countries. After all, legitimacy is the foundation stone of political stability. Of course, some seek to govern without a legitimate mandate or see their position eroded by conflict and opposition, but internal stability and external recognition are usually prerequisites of stable rule and effective government.

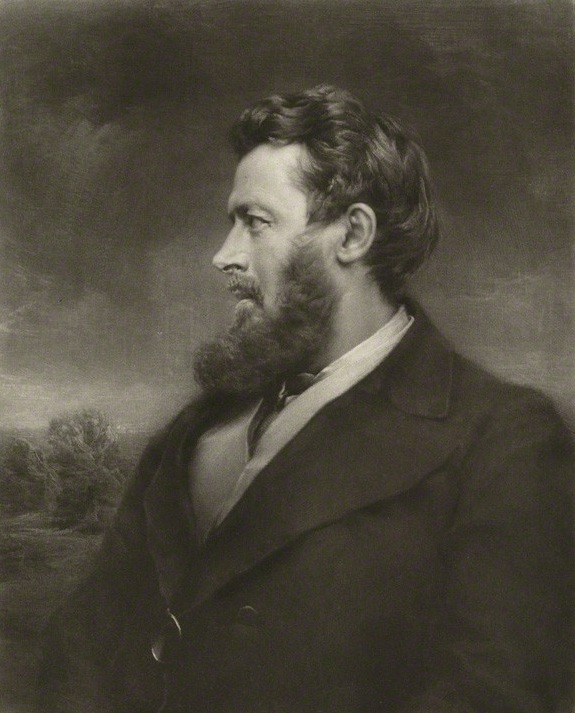

So much for the processes of transition. What of their effects? An executive President has significant power to shape a nation through legislation, the allocation of money and his/her active and passive interventions internationally. In contrast, a Monarch fulfils what the 19th century English journalist, businessman and essayist Walter Bagehot (1826-1877) memorably termed, the ‘Dignified’ part of the constitution, as opposed to the ‘Efficient’, or executive, function of government through Parliament, the Cabinet and the Judiciary. Further, in contrast to a re-electable President, who serves for a limited term, the Monarch’s role though still finite is longer-term, providing thereby ideally continuity, cohesion, and an exemplary template for national life. King Charles III’s official visit to the four nations of the United Kingdom after his accession, demonstrated his commitment to emulating his mother’s vision for national unity and political integrity.

But did Bagehot, writing his The English Constitution (1867) five years after the death of Queen Victoria’s (1819-1901; r. 1837-1901) beloved consort Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819-1861), consciously limit the role of the monarchy in light of the young Queen’s grief-stricken withdrawal from public life? Here is a telling passage from The Economist (quoted at the time of its publication by the New York Times):

The dignified institution of the monarchy is now also the only efficient one. Parliament, the Cabinet, the civil service – all the old machines of efficiency are creaking. And The Economist sadly concluded that ‘the very restraint and dignity with which the Queen … has exercised her job have provided [a] golden cloak to cover up the mediocrity’ elsewhere.

If you are nodding in agreement, you may be surprised to learn this article (by Anthony Lewis) appeared on 8 June 1977 amid celebration of Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee.

Let’s be clear. There are times when the monarchy of the United Kingdom finds it necessary to carry more weight institutionally. Why? Because of conflict overseas, turmoil in Parliament or in 10 Downing Street, or a hostile public mood. This was true during prolonged industrial strife of the 1970’s and fractious negotiations to leave the EU in 2017-2019. It has again been seen during the embarrassing implosion of the Johnson premiership. But the reverse is also true. The government has at times had to support a weakened monarchy; as, for example, in 1936, when King Edward VIII’s (1894-1972; r. 20 January to 11 December 1936) desire to marry the American divorcée Wallis Simpson (1896-1986) led to a political crisis and the King’s Abdication.

An elected President has no such ‘golden [royal] cloak’ to veil weakness or mediocrity. They must employ different tactics. French Presidents are famous for this. Earlier this year President Emmanuel Macron (b. 1977; Pres. 2017-present) sought to bolster his position – and pass the buck for his mistakes – by dismissing his Prime Minister, Édouard Philippe (b. 1970; PM 2017-2022) and appointing the experienced, conservative civil servant Elisabeth Borne (b. 1961). The message was all too clear: the Government is the problem not the President. American Presidents have adopted a different approach. In recent times – notably, between 1969 and 1993, when a Republican sat in the White House with a Republican minority in the Senate for all but six years (NB. in the House of Representatives for 20 of the 24 years) – lack-lustre leadership and/or inefficiency have been blamed on the Hill not on the Oval Office. Democracy comes at a price.

However attractive for ardent monarchists, it is dangerous for a monarchical regime to rely on public good will to cover a government’s failings or socio-political dysfunction. Fuelled by the media, public opinion is notoriously fickle. No, the best safeguard for the future of a constitutional monarchy is the efficiency of an elected government on behalf of every citizen. This protects democracy and the stability monarchy can bring.

One of the greatest challenges an elected Executive President faces is the expectation (and mandate) that they will act in a coherent way both as Head of State (including as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces) and as a political leader. When the then Deputy President William Ruto addressed Chatham House, London, earlier this year, he expressed the hope that there would be substantial, principled, opposition to the next Government of Kenya, whoever was elected. Like many, he drew attention to the value of an effective opposition party to sharpen legislation and protect the interests of all.

I have written before on the importance of the role of Leader of the Opposition (in the UK, the ‘Leader of His Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition’).[4] That was in the context of a strong parliamentary system with Government led by a Prime Minister and a Head of State with no political role other than the formality of appointing as Prime Minister the person commanding a majority in Parliament. In a country with an elected executive President, the Leader of the Opposition needs to be balanced by an effective ‘leader of government business’ in the legislature (whether or not he or she is called ‘Prime Minister’). In this way, the President, as Head of State, can be seen to be acting as the senior executive rather than as a partisan politician. With a trusted and effective leader of government business in place, the President can safeguard his/her position as a national figurehead who works for the good of all and, thereby, consolidates public support and unifies the nation. This requires, of course, the President be able to trust the leader of government business and not fear the creation, or perception, of a rival power base.

The role of Head of State is of the greatest importance to a country. It involves a delicate balance between the powers associated with the position, the character of the occupant, their longevity in office and their general acceptability to the country’s citizens. Elected Heads of State have enormous power, and, as a consequence, wise, effective republics restrict their term of office. But it is not uncommon for an elected President to function more as a figurehead than a force for good or ill in the everyday government of a nation. Their character and actions, though ultimately assessed in an election, can often be little known beyond the confines of the ruling elite.

Contrast this with a monarchy. As in the case of King Charles III, an heir may wait many years to accede to the throne, have had years to prepare for the role and have acquired a public persona with which he or she may or may not be comfortable. When they finally ascend to the throne, their powers (especially in a democratic country) will be limited to Bagehot’s ‘Dignified’ part of the constitution. But, in reality, their relationship to their citizens will be just as important (and complex) as that of an elected Head of State. Though not evaluated at a General Election, during times of national crisis (i.e., war or a natural disaster) or political upheaval, the monarch’s personal qualities, political influence, and emotional and perceptual capacity to the unite the nation, will be put to the test.[5]

The Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (b. 1971; PM. 2015-present) was asked in a recent interview on the BBC (19 September 2022) about the future status of the British monarchy in Canada, where King Charles III is Head of State (as he is of 13 other states)[6]. Trudeau spoke of the ‘steadiness and continuity’ in government that were safeguarded by the smooth accession of the new king and of the ‘extraordinary stability in our system of democracy’. He went on to say,

I think that we will increasingly appreciate the steadiness of having a system of government where we can have incredibly robust debates in Parliament on such divisive issues without having that divisiveness impact on people’s sentiment for the country at all, because we have an extraordinary Governor General[7] who embodies the best of Canadians, and we have a Crown that is overseeing, … sometimes from a comfortable distance, what is happening. There is a nice balance for the system we have which is going to serve Canada extraordinarily well.

So, what is the role of a Head of State, be they elected official or hereditary sovereign? Surely, maintaining national stability and peace in the midst of what appear to be increasingly fierce political debate, societal division and geopolitical tension, while all the while seeking to improve the lives and livelihoods of their citizens. Whether they are deeply and directly involved in day-to-day politics (as many elected Presidents are) or constrained by a constitution not to interfere (pace constitutional monarchs), theirs is a high, holy and demanding calling, for which all should wish President Ruto and King Charles III well in its fulfilment.

Jeremy Lefroy, Associate

[1] For the purposes of this article, I am only considering directly elected Presidents who have a strong executive mandate. There are, of course, many republics (i.e., Germany, Ireland and Italy) which are parliamentary democracies with a non-executive President as Head of State (sometimes directly elected, sometimes elected by parliament) who is non-political but fulfils roles such as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and represents the country abroad.

[2] The result was formally announced by Wafula Chebukati, Chair of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission, on 15 August 2022.

[3] Much has been and will be written elsewhere about the extraordinary life of Queen Elizabeth II, about her sense of duty, her willingness to adapt to change and about her role as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. In the latter role, she skilfully balanced her openly professed Christian faith with a commitment to the free exercise of faith (or not) by all her subjects.

[4] Cf. ‘Dignity in defeat: on the importance of ‘the Opposition’ (11 November 2020).

[5] E.G., in Russia in 1917, Germany and Austro-Hungary in 1918 (all during or at the end of WWI), Greece in 1973 (through a referendum)

[6] Cf. Antigua and Barbuda; Australia; The Bahamas; Belize; Granada; Jamaica; New Zealand; Papua New Guinea; Saint Kitts and Nevis; Saint Lucia; Saint Vincent and the Grenadines; Solomon Island; Tuvalu.

[7] The King’s Representative in Canada, who exercises the powers and responsibilities of the Head of State. The Governor General is currently HE Mary Simon (on the work of the Governor-General in Canada, cf. https://www.gg.ca/en/governor-general/role-and-responsibilities).